"Debra is a boxer, and the sex will be nuclear,/ the kind I will catch Chlamydia from for the first time,/ the kind her husband will kick the back window/ of my Plymouth in for, but this is the minute/ the CD Release Show is over, the microphones/ have spit out their cables, the cymbals have been tucked/ into their soft-shell beds, and my bandmates/ and I are celebrating with whiskey,” begins Atascadero native Ephraim Scott Sommers’ debut book of poetry, The Night We Set the Dead Kid on Fire.

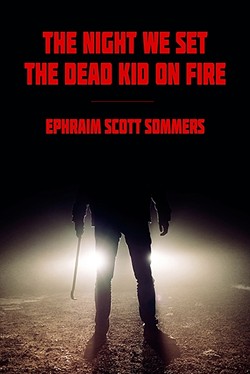

- PHOTO COURTESY OF EPHRAIM SCOTT SOMMERS

- STRAIGHT OUTTA A-TOWN: Singer-songwriter and poet Ephraim Scott Sommers recently released his epic debut book of autobiographical poems about growing up in Atascadero.

The singer-songwriter and former Siko frontman has gone far from his A-Town days, earning an MFA from San Diego State University and a PhD from Western Michigan University. He now teaches creative writing at the University of Central Florida and lives with his fiancée in Orlando, but somewhere inside, he’s still an Atascadero kid.

His opening poem, “Exhibitionism,” is absolutely epic—a mix of Charles Bukowski, Hunter S. Thompson, and Tom Waits—and seeing his history as a musician and the setup of a post-gig after party, one can’t help but wonder, how much is autobiography and how much is fiction in these poem/stories?

“The poems in The Night We Set the Dead Kid on Fire definitely walk the line between my own lived experience as a local musician in SLO County and experiences that I hope keep the reader entertained, and while what happens in ‘Exhibitionism’—the fight between two women in the street after a CD release show—is based partially on a true story, I also wanted to open the book with a sign post that says to the reader, ‘This is a book in which the speaker is not a hero or an authority,’” Sommers said in a recent email interview. “As a poet, I want to tell the truth about difficult experiences, so this means, for me, that I want to destroy any archaic notions the reader might have about the speaker/poet being above or outside of the community experiences illustrated in the poems. I have been complicit in some of the experiences in the book, and the reader needs to know that outright. I am also unafraid to indict myself in a poem, and it’s my hope that the reader might be more apt to hear me out if I do.”

- IMAGE COURTESY OF TEBOT BACH

- THE LIGHT AND THE DARKNESS: Sommers’ debut is full of narrative poems exploring “both mud and sunshine.”

Many of his characters seem to be dead-enders, like in “My Father Sings Dylan at Sixty-Two.” What draws him to create these characters?

“I think a woman who loves a man so much that she drives her Honda through the front of the house and into his living room is much more interesting than a lawyer who buys her husband a new BMW! Don’t you?” Sommers asked. “I like desperation. I like the messy emotions, and we need more of them in poetry! It’s important to note, too, that I don’t see the characters I write about in the book as dead-enders. I see them as rugged and loyal, blue-collar people who get up and go to work every day in spite of the wreckage around them. That experience—that maybe we don’t praise often enough in popular culture—is valuable. It matters. There is something so goddamned beautiful to me in that persevering. It’s what we do. We climb out of bed. We go on.”

Some of the scenes and lines Sommers creates are crazy, such as, “I am almost ready to receive the same father’s hand that sixteen years ago drove a crowbar through my girlfriend’s chin.” Where does he come up with this? It seems so real, like it happened. Maybe it did?

“I don’t believe in poetry that tries to educate,” Sommers said. “Instead, I believe a poem seeks to illustrate the experience of having a feeling in the concrete world, so I try to seek out the most difficult moments in my life and try to crawl around further in those moments where the scene is alive with the tension of the unanswered question. In that particular poem, ‘The Hardest Thing,’ the question is: Can I respond to someone who has committed violence against my lover with forgiveness when my entire upbringing and background says to start throwing punches? Most of my poems begin with a question I can’t answer. For me, it keeps the writing full of discovery.”

- READ ON : Signed copies of 'The Night We Set the Dead Kid on Fire' are available at ephraimscottsommers.com, or unsigned copies at tebotbach.org and on amazon.com. Sommers is planning a reading and book launch in SLO County sometime this summer.

His hometown of Atascadero shows up in “Labor Day,” “Cryin’ Bryan,” and “Hey Singer!” among others, and he paints a fairly rundown picture of it and its inhabitants. How did growing up there inform his poetry?

“Where do I begin?!?” Sommers asked. “Every weekend, in A-Town, when I was young, there were pallets burning, beer bottles being guzzled and shattered, and there was inevitably someone kicking the shit out of someone else with a bike pump or a skateboard or the heel of a work boot. I thought this was a normal childhood experience, this constant violence, and I’m still surprised, sometimes, that it was not.

“So there is definitely that gritty side of my hometown that finds its way into the poems because those are the scenes I witnessed growing up. But I’m also trying to praise the kind, loyal, hard-working, barbecuing, blue-collar people of Atascadero: the dishwashers, the truck drivers, the plumbers, the painters, the waitresses, the dudes pouring concrete, and the women working the front desk. These are the people who raised me to understand the value of a hard day’s work and the value of a dollar I earned myself.

“So I guess what I’m saying is that it isn’t all darkness or all light in my hometown or in my book, but a mixture of both mud and sunshine. Sure, there are STIs and fist fights, but there is also nakedness in restaurants and backflips into Triple Ponds, and kindness and laughter. In the book, I want to show you the full range of human emotion that is always possible in the town I love because that is what we do when we sing good blues—we sing the bad and the good at the same damn time! And I think we always feel better after singing!”

New Times Senior Staff Writer Glen Starkey can be contacted at [email protected].

Comments