- Photo courtesy of Vanessa Diffenbaugh

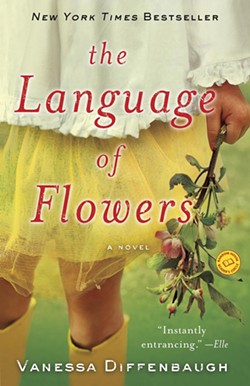

- BOTANICALLY BRILLIANT : Author Vanessa Diffenbaugh, pictured, is the founder of the Camellia Network, an organization dedicated to helping teenagers transition from foster care to adulthood. Her debut novel The Language of Flowers explores the difficulty and beauty of this topic through the eyes of Victoria, an angry young woman with a love of plants.

Vanessa Diffenbaugh’s debut novel The Language of Flowers is daringly, stubbornly, shamelessly romantic. And like its central character—the damaged, mistrustful Victoria Jones—you can try to resist its lovely overtures, but only for so long.

Set in San Francisco, The Language of Flowers, the Cuesta College Book of the Year, follows the young Victoria, a foster child shuffled from one institution to another. The book opens on Victoria’s 18th birthday, the day of her emancipation. She awakens to the terrifying realization that her mattress is on fire, a parting gift from the other girls in the foster home. This isn’t, we quickly come to understand, the worst thing that’s ever been done by one girl to another.

Victoria’s emancipation from foster care seems like the beginning of a life without hope or direction. For a short time, she lives at The Gathering House, an in-between home for other foster girls who have aged out of the system. After an initial period of free rent, which Victoria allows to pass her by without trying to find a job, she finds herself on the street. What sets her apart from so many others in similar situations, however, is her knowledge and love of plants, and, more surprisingly, her fluency in the Victorian language of flowers: Azalea for fragile and ephemeral passion, camellia for my destiny is in your hands. Victoria’s life thus far, however, has been better epitomized by the likes of thistle (misanthropy), basil (hate), or columbine (desertion). To her, the forgotten language represents a kind of secret weapon.

Victoria would be happy to live in McKinley Square with her little garden, sleeping under the trees, if it weren’t for the lack of privacy and, above all, her persistent hunger, which leads her to find work with a florist named Renata.

- THE LANGUAGE OF FLOWERS:

But despite her kindness, Elizabeth has acute weaknesses too. And we know from Victoria’s current situation that her life with Elizabeth—the woman who taught her the language of flowers—will come to an end, and intuit that it will be a bitter one, marred by the sorrow and guilt that will follow our protagonist into the present. Knowing this, the moments of maternal tenderness in these passages already feel nostalgic and wistful.

Readers get their first glimpse of hope, however, when Victoria thrives in her work at the florist’s. She listens seriously to clients’ wishes and carefully picks out the blooms with just the right meaning. Her almost magical way with flowers is quickly recognized by the shop’s clientele, many of whom return often, asking for her by name.

Is this, however, the book’s happy ending? Not even close. Diffenbaugh doesn’t deal in simplistic resolutions to lifelong struggles. Her protagonist makes touching, sincere progress and then throws it all away, recoiling from offers of love and assistance, and returning instead to the familiarity of misery, hatred, and isolation. She will break your heart, but you will root for her the entire time.

Through Renata, Victoria encounters Grant, a young flower salesman with ties to her rocky past. Grant knows the flower language, too, though his declarations of adoration are initially met, appropriately, with rhododendron—beware.

- PETALS SPEAK LOUDER THAN … YOU KNOW: Vanessa Diffenbaugh, author of Cuesta College’s 2013 Book of the Year, The Language of Flowers, will visit the Cuesta campus for a free reception, lecture, and book signing on Wednesday, Feb. 27, from 5 to 7 p.m. at the Cultural and Performing Arts Center. For information on more Book of the Year events, including films, an art exhibit, and several workshops ranging from supporting foster children to flower arranging, visit library.cuesta.edu/book.

In Victoria’s world, an often unforgiving place, every moment of sweetness feels hard earned. Set in San Francisco, the very epicenter of irony, Diffenbaugh’s debut novel is a work of guileless beauty.

Arts Editor Anna Weltner can be reached at [email protected]

Comments