I hate waiting. My first memory of the moment when waiting fades from boredom to fear to heart-stopping anxiety goes back to the night of Oct. 11, 1996. I was at my aunt and uncle's house in Atascadero, where my dad was staying at the time. I was 6 years old. I fell asleep asking my mom when my dad was coming back home to see me.

When I woke up he was dead.

As far as I know, he planned to come back that night. He hadn't gone far. The coroner's report lists the death of my father, Dana Michael Cooley, as "accidental."

On his last night alive, he had been home for one week after completing a rehab program for the second time in about a year, this one in Port Hueneme, near Oxnard. When he overdosed on that fatal hit of heroin, it was too much for his detoxed body to process. He died at a friend's house in a Paso Robles trailer park, just a mile away from my old elementary school. He was 35 years old. Police found him with the syringe still in his lifeless hands.

Some memories of my dad are sharp: One morning post rehab, I thanked him for making me breakfast, and he looked me right in the eyes and said, "I love cooking for you." There was also the night he put me in the bathtub and left the water running so long that I figured out how to turn off the water, climbed out, and went to find him. He was passed out in the living room unconscious, either from pills or heroin. Eventually he came to. Other recollections of my dad are soft and fuzzy around the edges. I have a blurry picture in my mind of both my parents waking me up for the first day of kindergarten.

Aside from my mom, the people who knew him best, his family, don't talk about him a lot. It brings back memories not just of the painful end of his life, but of the troubled childhood he and his four sisters shared. My aunt, who lived with my dad during the last days of his life, told me she wasn't up to talking about her brother when I said I was working on this story. She said a sadness came over her that she hadn't felt in a while.

Loss is hard, and it's murkier to navigate when the cloud of addiction settles in. More than 20 years later, with 22 reported fatal opioid overdoses in the county in 2017, my story is still far from unique.

Since 1999, just three years after my dad lost his battle with addiction, the U.S. has seen a dramatic increase in the number of pain medications, sedatives, and stimulants prescribed. Since 2007 deaths related to drug overdoses have increased in every county across the nation.

In SLO County, opioid-related overdose deaths more than doubled from 15 in 2006 to 37 in 2016. But there are glimmers of hope. According to preliminary data from the SLO Opioid Safety Coalition, there were just 22 opioid-related deaths recorded in 2017. If confirmed, this would be the first decline since 2012.

Drug addiction is a strange and endlessly hungry beast. Even as science continues to confirm that it is in fact a disease, we struggle on a personal and societal level to treat it that way. Yet people in SLO County and beyond continue to lose sons, daughters, sisters, brothers, husbands, wives, parents, and friends to the latest iteration of the opioid epidemic. These families, like me, have memories that refuse to fade as the community continues to tally up stories of loss and hope that mark the lives of those left behind.

Using for the rest of my life

Kim Lacey's tattoo is one of the first things I noticed when we met up to talk at Kreuzberg Coffee in Paso Robles on a sweltering summer day in June.

- Photo By Jayson Mellom

- PAYING TRIBUTE Kim Lacey, of Atascadero, with her husband, Dan Grahm, in their home, shows her tattoo that she got in memory of her son Ty after he overdosed on heroin in 2016.

A little red heart with wings outlined in black marks one of the Atascadero resident's inner wrists. It's the paralegal's first and only tattoo. She got inked after the 2016 death of her then 22-year-old son, Ty, who overdosed on heroin just days after being kicked out of a rehab program in Santa Cruz.

My first tattoo is on the inside of my left ankle—a loopy black signature of the name "Michael Cooley," pulled straight from my birth certificate. Lacey tells me her husband, Dan Grahm, also has a commemorative tattoo on his forearm, featuring their son's initials on a shield with a single wing behind it. The design comes from one of Ty's drawings.

Though toward the end of Ty's life he was close with his mother, it wasn't always that way.

"There was a time where I could barely speak to him without being angry," Lacey said. "We didn't have any exchanges."

Ty went to a yearlong therapeutic residential program in Utah when he was 16 to deal with issues surrounding defiant behavior and substance abuse. Lacey thought the worst might be over. He came home and picked back up with his pastime of pole vaulting, turned 18, and graduated from Atascadero High School. Things continued to look up when he enrolled at Cuesta College and got a job delivering pizzas.

But just a year into his schooling, Ty decided to drop out. A few months later, he started to sleep a lot more and missed work. Eventually he lost his job. He would get belligerent when his parents tried to talk with him about their concerns.

"I was trying to be really clear that he had to work and contribute," Lacey said. "People would say that he was just trying to find himself, but I sensed more. It wasn't OK."

Lacey found discarded needles in Ty's room and told him he had to move out. She didn't know what else to do.

"It's really hard to kick someone out onto the street when you know they're going to be homeless," Lacey said.

After wearing out his welcome on different friends' couches, Ty did become homeless. He would sneak back home from time to time to try and live in the yard. Once when Lacey and her husband were on vacation, Ty and his friends parked an RV in the driveway until the neighbors called the cops. Ty stole family heirlooms like silver and watches from his parents to get money for drugs. When Ty stole his father's truck one day, both of his parents finally pressed charges.

During one of many stints in jail, Ty and his mom finally began to build their relationship back up again.

"I just remember struggling," Lacey said of one of her first visits to see Ty while he was in jail. "Three hours is a lot of time to talk with anyone. We talked about the dog, people we had in common, what we were reading, pretty much kept it light. I wasn't trying to fix him."

After his release, Ty overdosed on heroin at a Starbucks in Atascadero in 2015. He called his parents afterward and told them he wanted to go to rehab. They drove down to a Salvation Army in Anaheim, because the faith-based program was free. But Ty wasn't admitted because he had outstanding probation violations.

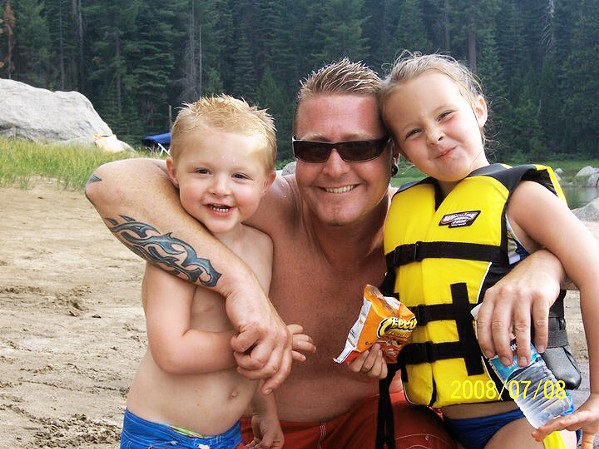

- Photo Courtesy Of Kim Lacey

- IN RECOVERY Kim Lacey (center) with her son Ty (left) and her husband, Dan Grahm, at Downtown Disney months before Ty died from a heroin overdose in 2016.

So they went home. When Ty was finally sentenced, he was told he had to go to residential rehab and had 24 hours to do so. So Lacey and her husband drove back down to Anaheim again. This time around, the medications Ty was on for ADHD and anxiety disqualified him from being admitted to the Salvation Army's program. And he didn't have a medical waiver from a doctor to come off the medications. There weren't any residential treatment beds available in the SLO area at the time, and no one from the county had told Lacey or her husband that Ty would be denied by the Salvation Army.

"It remains to me a real frustration that the county would discharge someone to deliver them to a program that's not going to accept him in the condition he's in," Lacey said.

Finally, Ty found a spot at a program in Santa Cruz called New Life Services. As part of rehab, Ty got a job and worked at the local Goodwill warehouse. On Mother's Day that year, 2016, Ty sent his mom a card saying that she inspired him.

"As he got clean, the kid I knew started to come back," Lacey said.

Then, a friend used Ty's nicotine vaping device inside the rehab facility, which isn't allowed. Both Ty and his friend were kicked out. Ty was told he could re-apply within five days. His parents put him up in a hotel room for a night until he could stay with a coworker who had offered their couch the following day. He got paid and reimbursed his mom for the room via Facebook.

"I was terrified of what could go on in that motel room," Lacey said. "Like all people being discharged from jail or rehab, you're in danger of relapsing."

The next night Ty stayed on his coworker's couch at her family's home. By morning, he was dead.

His friend's husband found Ty passed out on the floor in the middle of the night in the midst of an overdose. The couple was from South America and didn't speak much English, and the man couldn't figure out what was wrong with Ty and put him back on the couch. When they found Ty dead in the morning, the couple called the police.

It was close to noon on a Saturday morning and Lacey was pulling weeds in the front yard. She noticed a police car drive by. They live on a dead-end street so not much traffic goes by.

"'Thank God I don't have to worry that they're coming to my house,'" Lacey said she thought to herself. "And then I saw them stop and turn around, and then I knew. They pretty much had to pick me up and carry me into the house."

Do less harm

For more than a decade after my dad died, it seemed pretty cut and dry to me: Either you're using or you're sober. I've never done heroin. One hit and I was sure I'd fall in between the cracks to where no one could find me, just like my dad did years ago.

But I know now that addiction, sobriety, and recovery are nuanced. A lot of people spend much of their lives in those in-between places. Meeting people where they are is an idea that Katie Grainger wishes more people would consider. Until recently, she worked as an overdose prevention educator for the county and on the Naloxone Action Team for the SLO Opioid Safety Coalition.

- Photo By Jayson Mellom

- FINDING MEANING Sandy Wortley stands in front of Bryan's House, a residential treatment facility for women struggling with substance abuse. Wortley runs the home that she named after her son, Bryan, who died in 2010 after struggling with an opioid addiction.

"There's people who sort of believe in the Darwinian theory of addiction, but I think the thing that will help is just bringing back humanity," Grainger said. "With addiction there is a vilification and even a romanticism attached to it, and that can be a problem."

Preventing overdoses is personal for Grainger. Her ex-husband and the father of her young son is currently incarcerated on drug-related charges and was sentenced to nine years. He's eligible for parole in 2023. After the two divorced and Grainger was diagnosed with cancer, she said, he once overdosed on heroin five times in the span of two months. She knows he's only alive today because people in his life had access to naloxone, also known as Narcan. The drug is an opioid reversal medication that can save the lives of people in the throes of a deadly heroin overdose. The idea is that if people can just stay alive long enough, they'll eventually be able to pursue treatment.

"You have to kind of accept people as they are," Grainger said. "Abstinence isn't going to work for everyone. Pursue everything."

Although naloxone was approved by the FDA for use during opioid overdoses in 1971, it remains controversial. The SLO Bangers Syringe Exchange estimates that since they started distributing naloxone for free in 2017, there have been 171 overdose reversals in the county.

"The stigma is that they have character flaws, that this is a moral failure," said Lois Petty, site manager for the exchange. "Addiction is complicated. People want to demonize people who use drugs. Our drug policies are not effective. How does incarcerating somebody who has lost the will to see any kind of happiness help?"

And therein lies the root of the problem for people like Petty, Grainger, and other advocates for harm reduction: We treat drug addiction like the crime we've deemed it to be rather than the disease it actually is.

"Our county jail is our largest detox facility," Grainger said. "Instead of criminalizing people, we should work on healing society and work on creating a world that's worth living in for those who are suffering. And that's a lot harder to do; that takes everyone. Some people can't completely give up everything."

Ideally, Petty said that the people who come to the needle exchange in SLO every Wednesday would be able to inject their drugs on-site, in a safe space. But she knows that's a long way from happening on the Central Coast, even though San Francisco opened the first safe injection site in the country on July 1. While the idea is brand new in the U.S., facilities like Vancouver's Insite have seen no overdose fatalities on its premises since opening in 2003. The clinic does not supply any drugs. Medical staff is present to provide addiction treatment, mental health assistance, and first aid in the event of an overdose or wound. Last year, Insite recorded 175,464 visits.

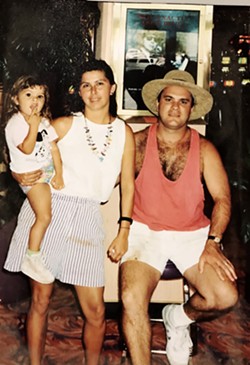

- Photo Courtesy Of Sandy Wortley

- A LEGACY Sandy Wortley's son, Bryan (center), left behind two children when he died in 2010 after battling an addiction to opioids. Wortley opened Bryan's House, a residential treatment facility for women struggling with substance abuse, in her son's memory.

But providing a space to allow people to put illegal drugs into their bodies doesn't sit well with everyone. Even a few years ago, I would have vehemently opposed the idea of the drug that killed my dad being freely used in a hospital-like setting. But I'm 28 years old now, just seven years younger than my dad was when he died. One day, I will have been on this Earth longer than he was. The closer I get to 35, the more I wonder. Had there been a facility like Insite in SLO County in 1996 or had naloxone been distributed to heroin users the way it is now, my father might still be alive today. The wisp of that idea, of what could have been, is just too emotionally powerful not to consider.

"Part of the solution is to stop treating addiction like it's something horrible," Petty said. "Harm reduction is treatment. We want people to be safe. We want people to be alive. They know we care about them. We value them, but we're not trying to fix them."

The other side

About a year after my father died, in October 1997, my mom (who now goes by Stacy Smith) read an article in the SLO Telegram Tribune (known today as simply The Tribune) that really upset her. It was an Associated Press wire story about a grandmother in Ventura who worked as a prostitute to make enough money to keep buying heroin to feed her addiction. The article ran in the same issue as an ad my mother had paid to run in the paper on the anniversary of my dad's death, featuring a family photo of me as a toddler with my parents on vacation, before they had divorced, with the words, "The surviving family of Michael Cooley would like to remind you that drug abuse doesn't just kill addicts. It kills sons, dads, brothers, friends, families, and probably someone you've known and loved. We wish Michael were here today and drugs were not."

- Photo Courtesy Of Ryah Cooley

- GONE TOO SOON New Times Arts Editor Ryah Cooley (left), as a young child with her parents Stacy and Michael Cooley. Her father died from a heroin overdose in Paso Robles in 1996. This family photo ran as an anti-drug ad in the then SLO Telegram Tribune.

That photo from my mom's ad now sits in my living room, a reminder of better days for our small family of three. Until now, I'd had no idea she'd run that photo and those words in the paper. She felt the story and the photo of the woman from Ventura glamorized drug use and that it was tactless to run her ad in the same issue.

"What kind of mixed message are you trying to send the youth of the county who may be inclined to read the paper?" my mom wrote in a letter to then-editor John T. Moore. The letter also ran in the paper.

Moore took the time to respond to my mom in a one-page letter of his own.

"My reaction to the story was completely opposite to yours," Moore wrote. "I found it initially sad that any individual would so waste her life. ... I can find nothing in it that would be construed as an encouragement for the lifestyle that this individual chose."

My mom appreciated Moore's response but still felt like he missed the point, which she laid out again in a follow-up letter.

"The bottom line is that heroin kills families, and leaves a messy puzzle to put back together for the surviving ones," she responded

I asked my mom recently why she chose to run that ad and write that letter to Moore.

"I felt like I couldn't do anything to bring him [Michael] back, but I could pipe up about it," she told me.

Like my mom, Sandy Wortley is another woman from North County who lost a young man in her life to heroin. Her son, Bryan, was just 32 years old when he died in 2010. I drove out to Paso Robles on a sunny day in June to talk with her at Bryan's House, a residential treatment center with beds for five women with substance abuse issues and their children. Wortley serves as the director, and her daughter, Alicia McAllister, is the program coordinator.

Sandy said her son got hooked on opioid painkillers after breaking his neck when he was 27 years old. He started doctor shopping and ordering pills online to get his fix. Around 2008, Bryan decided to get clean on Suboxone, an opioid blocker that at the time was used just for detox, but it's now also used for long-term recovery, which is what Bryan ended up doing. The drug eases the symptoms of withdrawal and prevents users from getting high if they do take an opioid while on it.

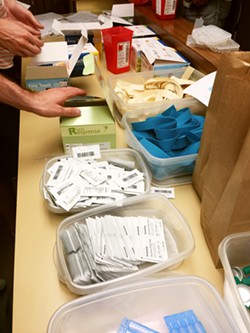

- Photo Courtesy Of Lois Petty

- HARM REDUCTION Volunteers at the SLO Bangers Syringe Exchange prepare clean needles and other supplies to give away to drug users in order to help prevent the spread of wounds and diseases.

However, Suboxone can be fatal when mixed with Xanax, which is what happened to Bryan. In 2010, he spent a week on the phone trying to get his doctor to give him a new prescription for Suboxone after he lost the first one. While at his grandparent's house in Brea, Bryan found some Xanax in the cupboard. There were just enough trace amounts of Suboxone in his body after not taking any for several days.

By morning he was found dead in the bathtub.

"To me it was like, why did this happen now?" Wortley said. "It's such a hard disease."

Previously, Wortley worked for the county as a counselor. When a grant came up in 2013 to open a residential sober living center, a coworker urged her to apply for it and name it Bryan's House, in memory of her son. When Bryan died, he left behind a wife and two young children. She said most of the women who come to Bryan's House now have a history of using heroin.

"We're helping people get clean so other kids won't lose their parents," Wortley said. "I just feel there was a purpose behind it, maybe this is it. Who knows. It's super healing."

My mom recently told me that she wondered whether my dad might still be alive today if he hadn't had such a traumatic childhood. I mused that maybe he would be alive still if naloxone was distributed in SLO County in the 1990s like it is today. It's easy to get lost in a world of what-ifs, but as McAllister reminded me when we sat and talked inside Bryan's House, heroin is a drug that moves quickly, leaving little time for course correction for those it snares in its trap.

"You either stay in recovery or you die," McAllister said. "It only ends two ways." Δ

Send comments to Arts Editor Ryah Cooley at [email protected].

Comments (5)

Showing 1-5 of 5