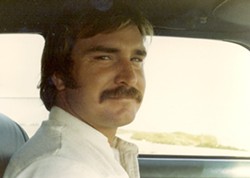

- PHOTO COURTESY OF MARK BROWN’S FAMILY

- GOOD TIMES : Mark Brown driving the family car in the early 1980s.

Mark Brown had been dead a month when his body was found in San Luis Obispo Creek. Brown was a 54-year-old ex-construction worker who had lived more than 20 years on the street, his life consumed by alcohol and drugs. No obituary memorialized his history or even mentioned his name and only a few other street people had noticed he was missing. A jogger found Brown’s body near the tent where he had lived the last months of his life, only a few blocks away from where his body would be held in limbo for three months.

Brown’s body was not taken to the county morgue; there isn’t one. Most counties in California have morgues but San Luis Obispo out-sources its morgue duties to local mortuaries. Reis Family Mortuary was on call that 2007 February day and Brown’s body was brought up from the creek and put in a narrow, refrigerated chamber. There it became the center of a conflict between his family and the county government: Who would pay to cremate or bury the remains?

How paupers’ remains should be disposed is not an uncommon question in San Luis Obispo County. Each year more than 100 families ask the county for help from its indigent burial fund to pay for cremation or interment of their dead relatives. The burial fund is intended to pay for processing anyone who dies in the county with no assets. Typically less than a third of those families get assistance and county officials said even fewer are getting aid this year, although nationally indigent burial assistance is increasing.

Many families are surprised to learn the county’s standards are very strict; the relative of an indigent must be nearly penniless to qualify for help. When the county refuses to pay and the relatives of the deceased don’t pay, the mortuary is stuck with the cost.

Of the mortuaries contacted for this story, only the Reis funeral home would speak openly about indigent burials. Representatives of two other mortuaries said it would not be “good for business” to speak openly about issues they have with the county. One said they had a body in storage, which neither the county nor relatives would pay to bury.

Brown’s body was in the same sort of familial and bureaucratic limbo, and became nearly as forgotten in death as Brown was in life.

Every state deals with indigent dead in a different way. Thirty-six states mandate counties must deal with the dead; fourteen states and the District of Columbia handle the task. Some states require physical burial for indigent dead. Massachusetts requires burial in a coffin with a nameplate and a clergyman present. New York City buries its indigent dead on an island off the Bronx filled with more than 900,000 bodies.

Since the beginning of San Luis Obispo County’s history, the government has been responsible for burying the unclaimed. Until the middle of the last century, the county buried abandoned remains in Potter’s fields segregated within local graveyards. The indigent were first buried wrapped in carpets and then early in the 20th century in simple pine coffins. After the passing of Proposition 13 in 1978, the county decided to save money by cremating all the indigent dead and scattering the ashes at sea.

The county divides its morgue duties among 10 or so mortuaries, which each take month-long shifts and cover a particular geographical area. The Reis Family Mortuary and Wheeler-Smith Mortuary & Crematory cover the city of San Luis Obispo. These two mortuaries process the remains of many homeless residents because there is a concentration of people without shelter there.

Kirk Reis remembers the night when Brown’s body came in. There was nothing different from hundreds of other bodies that he had seen come from the streets and the creek. The coroner discovered Brown’s identity and contacted his relatives, an ex-wife and two sons.

Sheriff’s deputies called Marcia Brown, Brown’s ex-wife, and told her he was dead. She wasn’t surprised by what had happened to him.

- PHOTO BY STEVE E. MILLER

- FALL GUY : Kirk Reis, operator of Reis Family Mortuary, absorbs the costs when families of the dead and the county can’t or won’t pay for the burial.

“There was alcohol and drugs,” Marcia said in a phone interview. “He became a different person, and then he was gone.” They divorced and Brown descended to the streets. Marcia said he would come by every few years but he never paid any child support. “He wasn’t a bad person,” she explained. “Drugs and alcohol just took him away from me. And that’s what killed him.”

According to his death certificate, Brown died of “chronic alcoholism.”

When they heard he had died, Brown’s two sons traveled to see what had happened to their father. Though they had seen him only a few times since he had left when they were 4, they both felt compelled to come. They were fortunate: The body had been identified by a homeless friend, so they didn’t need to view it.

“I know he was never much of a father,” said Cagney Brown. “But he was my dad, my DNA. I had to be there.”

An issue they didn’t anticipate confronted the two brothers: They were on the hook to pay the costs to bury their father. The problem was they didn’t have any money.

“I would have loved to have paid for it—and I could now—but back then I was in college and didn’t have any money in the bank,” said Cagney.

Reis referred the brothers to the county indigent burial plan run by the social services branch of the county government. The county did something that surprised Reis; they turned the Brown brothers down.

Reis was no stranger to the situation.

Reis runs the family mortuary that has been burying the county’s dead for 54 years. The building is in the adobe style and has the look of a church missing its bell tower. You have to ring the doorbell to get in. Family mementos adorn the entranceway. Small statues from the Hearst estate look down on visitors.

Kirk Reis doesn’t look like someone who runs a mortuary. He’s stout and balding and has the appearance of a friendly but serious bartender. Sitting at his desk, he shakes his head as he talks about Brown’s family and others like them.

His mortuary has been assigned morgue duties for the county for as long as he can remember, said Reis, who’s on call to take in bodies for the county several months of the year. “It may sound strange, but it’s a privilege to take indigent cases,” he said. “We’re the last people to deal with them in this world and we treat them with respect.”

When a family says they can’t pay he will refer them to the county and even help fill out the forms the county requires. He says the county has been turning families down more often lately.

He had seen many cases like Brown’s before and after but something about the situation struck him as a textbook example of a system gone bad. To Reis, the two brothers were a perfect case for the indigent burial program. Brown’s sons were in no position to pay for their father’s body. They had only seen him a few times in their lives, yet they were being held responsible for the burial of a man they never really knew.

Reis said the county told him the brothers had jobs and therefore could afford to pay for their father’s burial. When the county turns down a bill, the mortuary is stuck with the cost. The cost is not much compared to most privately funded burials—$1,112 according to county policy documents—but can add up to a burden on the mortuaries.

- PHOTO BY STEVE E. MILLER

- ON ICE : Mark Brown’s body reposed in this refrigerator for three months while who would pay for his burial was decided.

“Look, I get people who have problems paying for a burial and I work with them,” Reis said. “But I am not going to sue poor families who the county won’t help. What sort of person would I be? What kind of business does that?”

Reis would have to sue if he wanted to get his money. California and San Luis Obispo County have no legal mechanism to make a family pay for a relative’s funeral. Rob Bryn, spokesman for the Sheriff’s Department, said he could not remember his department ever working with the county or the courts to get money from relatives.

Reis wrote California Attorney General Edmund G. Brown, April 16, 2007, laying out his problems. Under California state law, the county coroner is responsible for the interment of the indigent dead, he wrote. He referenced California regulation 7104.1 of the health and safety code that states, “If, within 30 days after the coroner notifies or diligently attempts to notify the person responsible for the interment of a decedent’s remains which are in the possession of the coroner, the person fails, refuses, or neglects to inter the remains, the coroner may inter the remains.” California government code says, “If an inquest is held by the coroner and no other person takes charge of the body of the deceased, he shall cause it to be interred decently.”

The attorney general declined to get involved, writing that it was the policy of his office “that local governments will be primarily responsible for citizen complaints against their employees or agencies, and that appropriate local resources will be utilized for such complaints.”

Reis is not the only one to cite state codes. Most states don’t require relatives to pay for the indigent dead. California does and the county follows the rules to the letter.

The county makes clear where it gets its authority to deal with the indigent dead on a policy memo it gives to local mortuaries. It lists California Health and Safety Code Section 7100, which says, “The liability for the reasonable cost of final disposition devolves jointly and severally upon all kin of the decedent in the same degree of kinship and upon the estate of the decedent.” The section defines kin as wife, parent, or child of the dead.

The office of the county indigent burial program is on the third floor of the Social Services building, a bland modern structure on South Higuera Street. Tracy Buckingham, the assistant director of Social Services, said unlike many other county and state indigent burial programs, the county has lately given out less money to pay for the burial of the indigent. She said the program paid for the cremation of an average of 2.6 bodies per month last fiscal year (July 2008 to June 2009) compared to 2 per month for the last three months. She said eight to 12 families apply for benefits every month.

Though it’s clear Buckingham and two of her supervisors are deeply moved by working with mourning families, they are determined only those who they believe are truly needy get county aid. Buckingham and her team are thorough.

They admit they have to deal with relatives who have had little or no contact with their deceased kin. Even a son or daughter who had been abused by a parent can nonetheless be responsible for the parent’s burial.

Applicants who want the county to pay for an indigent relative must fill out an extensive application and submit to an interview to persuade the county to agree. All income must be disclosed, as must the contents of any bank accounts. All expenses must be listed, including childcare, rent, and car payments. The name and address of the applicant’s landlord must be listed.

- PHOTO BY STEVE E. MILLER

- TO ASHES : Mark Brown’s body was cremated in this oven.

“You can’t hide from us,” said Jenny Hart, a program supervisor.

The county’s standards are strict: If income exceeds expenses then the county generally won’t offer assistance. “We don’t want to put them on the street,” Buckingham said. “But we are the gatekeepers for the taxpayers’ money.”

She concedes that when the county doesn’t pay, the funeral homes have to “eat the cost.” The mortuaries have to work out the problem themselves, Buckingham said. She pointed out that no funeral homes have pulled out of the program.

Reis has been eating the cost for many years. After storing Mark Brown’s body in cold storage for three months, he cremated the body and gave the ashes to his family. He didn’t charge them; he never goes after families in court. He says it’s not the cost that bothers him, it’s that the county is turning its back on poor families that don’t match its standard of extreme poverty to receive help.

“It’s just not right,” said Reis. “It’s just not right.” ∆

Staff Writer Robert A. McDonald can be reached at [email protected].

Comments