Over the summer, a collection of 13 Paso Robles city leaders were asked to raise their hands if they thought the city has a gang problem.

Five hands went up.

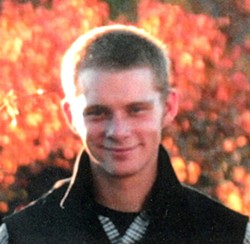

- PHOTO COURTESY OF BRADY FAMILY

- UNSOLVED : Police believe Bryan Brady’s death was an accident, but his family, through the help of a private investigator, suspects foul play.

“I don’t think they want to advertise that there might be a gang problem,” said one person who attended that meeting. “And I certainly understand that.”

That’s five people out of a room of 13—less than half of the people who thought there was enough of a problem to show up to the meeting in the first place. The meeting was organized by the San Luis Obispo County Anti-Gang Coordinating Commission, a federally funded group that pulled together community groups and organizations alongside the county’s Gang Task Force in 2007. Of the 50 people the Gang Commission invited, only a baker’s dozen showed up.

To make things weirder, the people who did show up filled out survey cards asking the same question they were asked by a show of hands. And of those survey cards, all 13 said they believe the city has a gang problem.

Maybe they were confused by the phrasing of the question, or thought it was too ambiguous. Or maybe they didn’t want to acknowledge publicly there might be a problem, even if they were willing do so privately.

Paso Robles is the fastest-growing city in San Luis Obispo County, but it’s still a small town by most accounts. Despite a population bump of 5,000 people in the last decade, brought on largely by a burgeoning wine industry, the city is still small, with a population of about 30,000. It’s a quaint community more associated with vineyard tours and fine dining than gangbangers and drive-bys.

But over the past few years, gang violence has been on the rise throughout the county, particularly in the northern areas and especially in Paso Robles.

“There’s been an increase in violence in North County, I think it’s pretty safe to say, and some of it is directly tied to gangs,” said Sheriff Ian Parkinson, who championed gang crackdowns in his campaign for the job.

Cases with gang enhancement charges prosecuted by the SLO County District Attorney more than tripled from 2006 to 2010 as gang-related cases steadily increased from one year to another.

Deputy Mike Hoier, who’s been assigned to the SLO County Gang Task Force for the past six years, said Paso has seen a significant upswing in activity over the past six or seven months.

“That’s kind of been the hot spot,” he said. “I don’t know why.”

Outside the general acknowledgment that gangs are as much a part of Paso’s new identity as are wine and fine dining—in fact, gangs have been around longer than the wine industry—there’s a well-established perception that many would rather just ignore the problem.

When asked for statistics on gang-related charges in Paso, Chief Deputy District Attorney Jerret Gran laughed sarcastically.

“We don’t have a gang problem,” he chuckled wryly.

But really, he added, an upswell of Norteño gang members from surrounding areas are beginning to clash with the area’s primarily Sureño population.

“That’s instant rivalry,” he said.

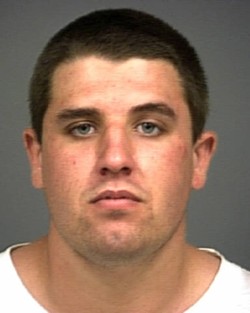

For example, 21-year-old Paso resident Steven Durrett was arrested in June along with his brother Richard Garcia, also 21, from King City, after a drive-by shooting that sent one man to the hospital with a bullet in his leg. Witnesses told police that Durrett and Garcia claimed to be “reds”—Northern California gang members—fighting back at “Scrapas”—southern gang members. One witness said it was a “Northern versus Southerner” thing, according to the police report.

And in March, police arrested 25-year-old Jose Alcaraz after a shooting occurred following a 10- to 15-person fight at a San Miguel bar. According to the sheriff’s report, the incident may have stemmed from bad blood between drug traffickers trying to establish business in northern Paso. Police believed the fight also broke out because some people had affiliations with the Paso Robles 13—with monikers like Chucky, Mingo, and Stomper—as well as other gangs, including the Shandon Park Locos.

The defendants in both cases have pleaded not guilty and are awaiting trials.

When New Times asked all the current Paso city councilmembers and City Manager Jim App for comment on the gang situation, they had little to say.

App declined to comment and deferred all questions to the Police Department. Mayor Duane Picanco requested a phone interview but then never followed up. Only Mayor Pro Tem John Hamon gave the following written response:

“I am aware of gangs in our town along with many others up and down the coast. Most recently the influence from the north, Salinas and King City. I fully support our Police Department and their efforts to keep our Roblans safe and without too much exposure to their presence. Our graffiti program is outstanding with volunteers performing restoration work within hours showing this group that Paso Robles has a 0 tolerance for [these] activities. With the poor economy, brings crime. Always will, so we must keep our Department strong and with a presence to this element that sends the correct message, their activities will not be allowed in our town.”

Except when they are.

The perplexing case of Bryan Brady

When police found Bryan Brady in mid-2010, the 78-car tanker train that hit him had severed his left leg and left hand, and crushed his head so badly it “caused the brain to be forced out of the body,” according to the police report. If not for the fact that his body broke an air hose, forcing the train’s emergency brakes to deploy, the Union Pacific conductors probably would have thought they’d run over some trash. At least, that’s what they thought they’d hit, according to police reports.

After the train ground to a halt, the conductors found Brady’s body parts scattered around the tracks. His upper body was lying face down, smelling of alcohol, covered in lacerations, bruises, grease, and oil, splayed across the tracks.

The end of Brady’s life was almost cliché in its tragedy. A punk kid who’d racked up his share of arrests and run-ins with Paso cops, Brady was cleaning up his act the year before he died and was working with his dad at the Robert Hall Winery in the eastern mecca of Paso wine country.

Regardless of his clean-up job, Brady still got stopped regularly and had trouble shaking the persona of a drugged-out raver.

“The cops always hated Bryan,” one of his friends told New Times. “He was kind of a trouble-maker, a rabble-rouser.”

Indeed, officer Jeffry Bromby (who has since retired amid unrelated criminal allegations), was the first to respond to the site of Brady’s death and identify the man by reputation and a signature tattoo on the back of his neck: a bar code and his birthdate, July 31, 1989.

The scene was cleared within a few hours. Officials from the Paso Robles Police Department teamed with Union Pacific’s investigative team and gathered Brady’s belongings, including his backpack, a diary with the last dated entry about two weeks prior, and his wallet and cell phone, which were lying a few feet away.

His driver’s license was missing and still hasn’t been found.

- PHOTO COURTESY OF SLO COUNTY JAIL

- NO SCRAPAS : Twenty-one-year-old Steven Durrett was arrested and charged with attempted murder with a gang-enhancement charge for a drive-by shooting in Paso Robles. Witnesses told police he was fighting back at “Scrapas.” He pleaded not guilty.

But they had a suspected cause of death: Brady killed himself.

It was the coroner who told Brady’s parents—Kasi and Don—their son was dead. Just the night before, though, the three had been out on the town, celebrating Brady’s 21st birthday. His parents took him out for a few drinks early in the night, then handed him 20 bucks and he took off with some friends.

His parents never bought the suicide explanation, but according to police, after a rough night spent drinking until closing time, Brady wandered to the tracks, laid down, and waited for a train to come.

The police recently ditched the suicide theory, but no one knows for certain what happened to Brady—or at least what occurred between about 3 a.m. when he was last reported being seen, and 6:15 when the train hit him. According to Brady’s parents, the police later revised their conclusion and determined Brady probably left the bar drunk with a blood-alcohol level more than twice the legal driving limit. Perhaps he got tired and laid down on the tracks, and then fell asleep.

According to Chief Lisa Solomon, “We feel comfortable in the conclusions we’ve come to.”

All of the police leads to the contrary either dried up or turned out not to be true, according to the department. Detective Michael Rickerd told New Times there is “no evidence of a homicide except speculation.”

Even the coroner found no signs of trauma to the head other than the injuries from the train. But those conclusions have since been debunked by witness accounts.

The Bradys don’t buy this new explanation, either. They hired a private investigator who’s been poring through police reports and interviewing and re-interviewing witnesses in the months since Brady’s death. Not only do the Bradys now believe their son’s death was no accident, they think they know who’s responsible.

At least one witness, who was the last person to see Brady alive, according to a police report, said his final night was spent in bar brawls.

Though Paso PD declined to release its report on Brady to New Times, the paper did manage to obtain a copy. Though the case is effectively closed and the paperwork is classified as a supplemental incident report, it details multiple fights and some allegations that Brady didn’t fall asleep on the tracks—he was put there.

Brady was involved in two fights the night before his death, the last of which left him unconscious after he was ejected from Pappy McGregor’s (formerly the Crooked Kilt) in downtown Paso.

One of the bar’s employees told police—she was interviewed about a week after Brady’s death—that she saw Brady get in a fight with about five Hispanic males, some of whom she thought were members of Paso’s oldest gang, the Paso Robles 13—or PR 13—because some had the number 13 tattooed on the backs of their necks.

Brady and the other brawlers were kicked out of the bar. And while no one testified they saw the fight, employees saw Brady shortly thereafter lying unconscious on the ground for anywhere between three and five minutes.

His assailants were never found or prosecuted.

From there, everything gets murky. Some people said they saw Brady getting dragged off by a group of men in the direction of the train tracks. Others said he was severely drunk, but refused to take a cab and then wandered off to the tracks alone. Other witnesses told police Brady was threatening suicide, that he was saying “nobody could help him.” Still others said he just wanted to get home.

It wasn’t uncommon for Brady to walk along the tracks on his way from downtown to his parents’ house. But if he was in fact heading home that night, he likely would have headed south rather than north of the bar, where his body was eventually found.

Furthermore, Brady’s parents and their private investigator allege that some of the witnesses police interviewed were associated with PR 13 or in the gang themselves. Others later told the family the police didn’t get an accurate story from some witnesses because they didn’t “ask the right questions.”

Several witnesses even came forward afterward to say they heard people bragging about killing Brady by putting him on the tracks. And some who spoke up now say they’ve been threatened for talking. One such witness was in jail with one of the potential suspects, but by the time police got to the suspect he had died of a drug overdose.

Overall, Brady’s parents think police have let leads slip away, or delayed interviewing a witness while a detective took off for vacation, for example.

In fact, at one point police had a witness who agreed to submit to a polygraph test. He was arrested before they brought him in, but the polygraph was never administered even while he was securely in custody.

Other witnesses told the police Brady approached them intoxicated, then left saying no one could help him, but they, too, are friends with known gang members, according to the Bradys’ investigator.

On Oct. 5, Brady’s parents filed a lawsuit against Pappy McGregor’s for wrongful death and negligence. In the lawsuit they claim bar employees should never have let Brady enter the bar drunk and they should have called 911 when he was found unconscious. If they had helped, his family alleges, Brady would still be alive. The bar hadn’t filed a response to the lawsuit as of press time.

The police maintain there was no foul play involved in Brady’s death, and though he was in several fights that night, there was no indication that anyone other than himself placed him on the tracks.

- PHOTO COURTESY OF SLO COUNTY JAIL

- SHANDON VS. PASO : Twenty-five-year-old Jose Alcaraz was charged with attempted murder with a gang-enhancement charge after a shooting that occurred outside a San Miguel bar, allegedly because of clashes between Paso Robles and Shandon gang members. He pleaded not guilty.

Only one witness named in the police report returned a call for comment, but said he didn’t have any more information than what he told Paso PD.

And if there is a gang presence in downtown Paso, at least one employee with a downtown business said he doesn’t see it anymore. He said there were issues three or four years ago, but things have gotten better since then.

“We basically stopped letting them in because there was just a bad vibe in general,” he said.

The perfect storm

Through a variety of factors, Paso is prime for a surge of gang and other criminal activity.

Consider this: The economy sucks, the Police Department has lost a third of its patrol officers, and preventative programs have been cut in the name of budget solvency.

Paso’s police ranks are stretched so thin—down from 41 officers in 2007 to 27 in 2010, though the City Council just approved hiring four new officers—that the department has instituted “safety response level,” meaning that when some officers are busy, the rest return to the department and will only respond to priority calls.

In September, the Police Department announced a joint operation with the SLO County Sheriff’s Department called Safe Streets, aimed at suppressing gangs. The initial sweeps have been successful, with arrests for crimes ranging from narcotics to drunk driving.

But the move was still scoffed at in some public forums, such as Dan Blackburn’s calcoastnews.com article titled, “Confronting north county gangs—finally.”

Chief Solomon and other Paso gang officers don’t get where these perceptions come from. Safe Streets, for example, evolved from a spike in crime combined with Sheriff Parkinson’s initiative to tackle gangs in the county. Still, Paso police emphasize that they don’t see indications of a turf war, for example.

Detective Rickerd said of some recent shootings, in which the suspects have been charged with gang enhancements, “They’re completely separate events. They’re not related whatsoever. … These are just events that unfold that happen to [involve] gang members.”

Paso police and other community members point to the influx of current and former gang members from “urban” or “metropolitan” areas—the really bad guys who migrate from areas like Salinas, King City, Santa Maria, and Los Angeles, to start up trouble in quiet places like northern SLO County.

The problem with this theory is that the recent rash of gang shootings in Paso involved local suspects, not just gangbangers from surrounding communities.

Within SLO County, Paso is showing the most signs of problems. According to the SLO County Probation Department, 27 percent of juvenile referrals last year came from the Paso/Shandon/San Miguel area, far more than any other region in the county. And out of the 791 kids booked into Juvenile Hall that year, 202 were from Paso Robles/San Miguel—again, more than any other region in the county.

Many Paso locals aren’t surprised there’s been an increase in gang activity, they’re only surprised that it happened so soon. As Rich Benitez likes to say, it’s “déjà vu all over again.”

When he first moved to Paso Robles in the late ’80s, Benitez remembers that the chief of police at the time told him there wasn’t a gang problem in the town. Then the local paper started to clog with news of gang-related shootings.

“And that was the first time I heard of PR 13,” he said.

PR 13, or the Paso Robles 13, is the oldest and most widely known gang in Paso Robles. It’s a Sureño gang, one of several common Hispanic street gangs that spawned in the state prison system along with Norteños.

On the website Urban Dictionary, one user posted a definition of Paso Robles 13 that reads: “The Southern Locos Gang is a crew of the most down ass Sureños in 805 Cali. They throw up SLG 13, and put down for their varrio, which is Atascadero, Templeton, Santa Margarita and Paso Robles. They smoke busters like chronic, and party like sailors on an all-day pass. You fuck with them and you end up six feet under.”

Some cops don’t like to name specific gangs, or give them any chance at earning notoriety in the press. Paso police say gang members will save newspaper clippings of crimes they’ve committed like trophies. But local law enforcement members who deal with gangs—and indeed many Paso residents—know the gangs and they know the members. Solomon said the PR 13 can be traced to one person in the early ’70s who came to Paso out of a state prison, though she wouldn’t give a name.

Paso’s gang problem peaked in the early ’90s. At the time, Benitez and other residents like Vicky Jeffcoach formed the Oak Park Recreation Center, which inspired a number of similar programs aimed at giving local kids something to do rather than stomp around with their friends and get into trouble.

Not only did it work, said Jeffcoach, a former youth coordinator for the city, “it was overly successful.” The Oak Park program gave kids—with about 400 enrolled at any given time—a place to go and goals to work toward, like skiing trips and outings to Six Flags. These days, Jeffcoach keeps several binders full of newspaper clippings and letters from kids who grew up in the program, thanking her for giving them what they needed to stay out of trouble.

“I didn’t know what to do in my life,” one kid wrote to Jeffcoach. “I would ditch school all the time. I didn’t care for anybody. I didn’t care for myself. I was on the verge of doing bad. I never knew right. Somehow I ended up at Oak Park. You took me in with open arms. I don’t know what you saw in me, but I felt special because you made me feel good about myself.”

But Oak Park’s services were reduced in May after the Paso City Council cut its share of funding—about $20,000—to shore up budget deficits.

“We had organizational things in place, and now they’re all gone,” Jeffcoach said.

One local official who works with gangs called Paso’s current climate a “perfect storm.” He comes across kids now with three dots on their hand to show their gang affiliation—young teenagers who tell him “I’m loco … I’m down for my hood.”

And now they have someone to fight.

According to local officials, the arrival of Norteño gang members from King City and other parts of Monterey County has led to clashes with Paso’s Sureño gangs, as well as other gangs in the surrounding area, such as “The Wolf Pack,” for example. Some people may not see a problem, though, explained the gang official—who asked to remain anonymous—because as long as it’s poor white kids hurting each other, or poor black kids, or poor Latinos, “it’s not a problem.”

Meaning, it’s not their problem.

“I think there might be some denial,” he said. “Because it is a place where folks come and spend some money and maybe have some wine.”

Bryan Brady’s dad Don Brady’s perceptions of Paso have certainly changed.

“Collectively, we’ve all got our heads in the sand,” he said. “Until it affects us.”

Paso police don’t agree with or like the idea that they or others in the community are “burying their heads in the sand.” Detective Rickerd said he deals with gangs all the time. There are perhaps 20 to 25 PR 13 members at any given time, but the police talk with them regularly and keep an eye on who’s causing problems.

Yet the perception is there, perhaps even within the gangs.

“They’re more in your face than they ever were before,” gang commission Coordinator Marci Powers said. ‘… I don’t know where this is headed, I just know that there is a lot of concern.”

Powers wanted to stress that Paso’s situation isn’t “hopeless,” that there are suppression efforts like Safe Streets. And the Probation Department is drafting a gang assessment to be released soon. Though Oak Park was gutted, there are other preventative programs like Generation Next and the Boys and Girls Club that help curb “the evolution of behavior that goes on that results in kids ending up in these gangs,” she said.

Others sound more desperate. After seeing kids he works with falling into the gang lifestyle because they essentially have nothing else to fall into, one official said it’s time for Paso to take a serious look at the world its kids are growing up in.

If not, he said, “we’re going to lose them.”

News Editor Colin Rigley can be reached at [email protected].

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1