Born in California, Ron Eto Kikuchi was just 18 months old when he was imprisoned by the United States government, solely on the basis of his Japanese ancestry.

Ron and his mother, Susy Eto Kikuchi Bauman, were taken first to Colorado and then to Arkansas under President Franklin D. Roosevelt's Executive Order 9066, which forced all people of Japanese ancestry living west of the Rocky Mountains in the United States to be imprisoned in concentration camps. Ron's father, Leo Kikuchi, enlisted in the Army "to show our loyalty to the United States of America," Ron said. Leo died fighting for his country.

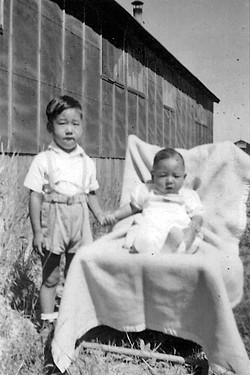

- Photo Courtesy Of The Cal Poly Susy Eto Bauman Collection

- FAMILY LEGACY Ron Eto Kikuchi is the grandson of Tameji and Take Eto, and the son of Susy Eto Kikuchi Bauman and Leo Kikuchi. Ron, posing next to his baby brother Gerry, is 3 years old in this photo taken at an internment camp in Arkansas.

Not long after arriving in the prison camps, Susy gave birth to Ron's brother Gerry. He was delivered by a man also interned in the camp named Dr. Taira.

Flash forward about 60 years later to 2002. Susy was strolling through the newly unveiled Eto Park on Brook Street in San Luis Obispo when she was introduced to Mary Taira, who served as an interpreter for leading Japanese garden architect Kodo Matsubara while he designed Eto Park. That's when Susy made a fortuitous discovery: Mary was married to Dr. Taira, the man who delivered her son Gerry in Arkansas decades earlier.

"After all those years, those two reunited in that little patch of grass there in that park," said Jim Brabeck, a longtime SLO Rotary Club member and CEO of Farm Supply Company. "I thought that was pretty profound. ... I just got goosebumps. What are the chances of that after all these years?"

Brabeck was a key initiator for having Eto Park created and dedicated in honor of the Eto family 20 years ago in May 2002. The park was refurbished in honor of its 20th anniversary, and a rededication ceremony was held on May 12, 2022, attended by community supporters and members of the Eto family, including 102-year-old Susy.

Masaji Eto, Susy's brother, worked alongside Brabeck at Farm Supply for years.

"He had been chairman of the board of directors and very influential in the business community as well," Brabeck said. "His [and Susy's] father, Tameji Eto, had been very instrumental in agriculture with the Japanese community."

But when the United States' Japanese internment policy began during World War II, what was once a thriving community was torn apart. People of Japanese descent in California were forced to leave their livelihoods behind for prisons far from home. What was once Eto Street was renamed Brook Street in 1942.

People who owned farmland, like the Eto Family, had something to come back to after their forced internment ended.

"They turned their land over to neighboring farmers," who maintained the land until they returned, said Dan Krieger, a Cal Poly professor emeritus and historian who has studied the Japanese American experience in SLO County for decades and wrote two books about it alongside his wife, Liz Krieger. He is so close to members of the Eto Family that they consider him family and call him cousin.

But most Japanese Americans working in agriculture didn't own their farmland, they leased it, Krieger said. When the internment policy ended, those without land had nothing to return to, and instead took up non-agricultural jobs in more urban areas like Los Angeles.

"We had over 1,000 Japanese residents [in SLO County] in the 1940 census, and we had fewer than 100 in the 1950 census," Krieger said.

- Photo By Malea Martin

- PAYING TRIBUTE Jim Brabeck, a longtime friend of the Eto family, spoke at the May 12 Eto Park rededication.

Ron was too young to remember his time in the prison camps, "other than what my mother has told me," he told New Times.

"I did not even know my father," Ron said. "He was killed in action in the famous 442nd combat team comprised of all Japanese American boys ages 18 to 20 who volunteered while we were in prisons."

The 442nd Infantry Regiment is known for being the most decorated combat team in U.S. military history. Ron's father, Leo, enlisted in the 442nd, Brabeck said, while his mother- and father-in-law (Tameji and Take Eto), his wife (Susy), his son (Ron), and his unborn son (Gerry), were all incarcerated.

"He loses his life on Anzio Beach fighting for his country," Brabeck said. "That's a huge sacrifice."

After the war, many members of the Eto family returned to San Luis Obispo to begin rebuilding their livelihoods. But with Eto Street having been renamed during the war, for many years there was nothing honoring the family for their contributions to the Central Coast and the unjust imprisonment they faced. So Brabeck hatched a plan: At the end of Brook Street, there was an abandoned park being used for overflow parking.

"That triggered the idea that maybe we could put a little park there, so we reached out to the city," Brabeck said. "That was the beginning of Eto Park."

Tucked away from the nearby busy streets of South Higuera and Madonna, Eto Park is a quiet, meditative oasis. A Japanese maple tree bursts with bright red foliage, and a stone bench offers a place to sit and take in the peaceful surroundings.

During the May 12 rededication, Eto family descendant Karen Nagano read a poem she wrote for the original park dedication 20 years ago titled A Garden. The crowd was silent as her words cut through the light SLO breeze: "Our hearts seek a garden; / Ground for the seeds / We receive in cupped hands: / Seeds of forgiveness, / Of love, / Of peace, / Of trust. / Our hearts seek a garden. / This garden. This." Δ

Reach Staff Writer Malea Martin at [email protected].

Comments