At 6:20 a.m. on Friday, Nov. 30, 2012, 22-year-old Chelsea Brunelle was struck and killed by a Ford F-250 traveling on Highway 1 in the Arroyo Grande area. Everyone can agree on that.

In the months since her death, a complex web of information, misinformation, emotions, and disputes has confounded law enforcement, mental health officials, and her family—all of whom are seeking closure.

For law enforcement, Chelsea’s death remains an open investigation. San Luis Obispo County Sheriff’s Department officials told New Times they’re being thorough in their casework and want to find a resolution as soon as possible.

For Chelsea’s family, the protracted investigation has aggravated the grieving process, and has, for them, exposed some disturbing flaws in the criminal justice and mental health systems.

On a recent afternoon, Chelsea’s family, still grieving and tearful, spoke with a New Times reporter at their house in Oceano.

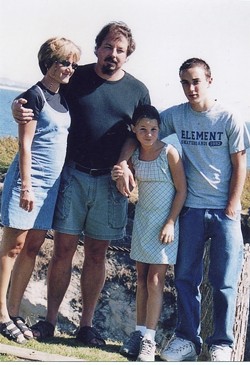

- PHOTO COURTESY OF JULIE MCDOUGALL

- ELUSIVE CLOSURE : Chelsea Brunelle—pictured here at a young age with her mother, stepfather, and brother—died on Nov. 30, 2012. Her family, law enforcement, and mental health organizations have been grappling for closure ever since.

Chelsea’s mother, Julie McDougall, has led a crusade over the past seven months to, as she put it, “make sure Chelsea’s death isn’t in vain.”

“You can’t replace a 22-year-old girl’s life,” McDougall, 47, said. “My biggest reason for pursuing this is to make sure everyone is held accountable; we don’t want to have any other family go through this.”

As McDougall tells it, her whole family was rocked by the shocking suicide of her husband Jim—Chelsea’s stepfather—in 2009. Chelsea was dealing with depressive feelings and seemed to manage them for years before entering a severe downward spiral in September 2012.

Justin Hultzen—Chelsea’s brother—said that’s when she started drinking, stopped sleeping, became increasingly violent, suffered wild mood swings, and often voiced suicidal thoughts.

According to Chelsea’s family, she was admitted to the SLO County Mental Health Clinic four times over the span of just one month, and each time, she was placed on 72-hour psychiatric hold.

McDougall, a registered nurse, alleged that despite the 72-hour stipulation, Chelsea’s recorded attacks on her mother and fiancé, frequent suicidal talk, and an expanding history of mental illness, Chelsea often wasn’t held for the full 72 hours.

New Times, in examining a bill to Chelsea from the clinic, found evidence to indicate that Chelsea wasn’t always kept for a full three days.

“I think it’s ridiculous,” Hultzen, 27, said. “These are the professionals; these are the ones who were supposed to save her life.”

A few weeks after her last discharge, Chelsea was arrested for public drunkenness in Oceano on the night of Nov. 28. The deputy who arrested her that evening was unable to see any of her mental health history.

According to Sheriff’s Department spokesperson Tony Cipolla, that’s standard practice. Deputies aren’t given access to mental health records when they run driver’s licenses.

According to McDougall—who wasn’t there, but heard an account from Chelsea’s fiancé—Chelsea screamed as she was pushed into the back of the car: “If I go to jail, I’m going to kill myself.” She was taken to jail.

Two days later, she jumped out of her fiancé’s moving car and into traffic. She was killed instantly.

Hultzen said the family received a call on their home phone from a mental health staffer more than a month after Chelsea’s death. The staffer was calling to follow up on Chelsea’s health, completely unaware she had died.

“For me, that was the epitome of a system that is completely broken,” Hultzen said. “It was almost laughable, in a very sick way. It’s like her life didn’t mean anything.”

Hultzen and McDougall likened the understaffed county mental health system to a revolving door, saying the system pushes people out as fast as possible in order to deal with the next influx.

For law enforcement, the main hang-up in the case has been the difficulty of procuring Chelsea’s mental health records. Jeff Nichols, the detective coroner assigned to Chelsea’s case, requested the health records two days after her death, but was denied a few weeks later.

SLO County Mental Health Services didn’t respond to New Times’ repeated calls for comment.

According to Cipolla, the complicated legal process (including research, strategy, and departmental proceedings) of preparing a subpoena to re-request those records is still ongoing. Most recently, Nichols presented the final subpoena in court on July 2 to a judge, who will determine what records should be released.

Cmdr. Ron Hastie, also with the Sheriff’s Department, said he understands the frustration of the family, but remains committed to investigating the case by the book.

“Our office is here to help the family, and we are trying everything we can do to get these records in order to reach a conclusion,” Hastie said. “Sometimes, people aren’t happy with the process, or the length of time for investigating a case, but that doesn’t change the fact that there’s a process. We cannot change how the court works. We are getting closer. We want the same resolution.”

When asked about the lack of communication between law enforcement and mental health, Hastie admitted there wasn’t much overlap between the two.

“They have their protocols, and we have ours,” Hastie said. “Sometimes, they don’t mesh.”

For Chelsea’s family, more than seven months of waiting is too much.

“It’s been immobilizing for us,” Hultzen said. “We’ve been functioning at a minimum basis, at best, for the past seven months. It’s not only dealing with the loss of Chelsea, but also dealing with the lack of basic answers from mental health and law enforcement.”

Much like law enforcement itself, McDougall and Hultzen have been denied access to Chelsea’s mental health records. According to McDougall, staffers there have cited HIPAA laws and told her she has to become the executor of Chelsea’s estate in order to gain access.

For Chelsea’s family, there’s no doubt in their minds that her death was a suicide. Having access to the full story and ending the investigation, however, would bring them some much-needed closure with the system they said failed Chelsea.

“She was looking for help, and she didn’t get it,” Hultzen said.

Staff Writer Rhys Heyden can be reached at [email protected].

Comments