Editor's note: This is the second installment in a series documenting the prevalence of fentanyl in SLO County. The first, "Two Central Coast mothers lose their sons to accidental fentanyl consumption and want to warn others," was published Jan. 21.

As Cindy Cruz-Sarantos speaks about her late son, Dylan Kai Sarantos, a smile spreads across her face. She describes him as an individualistic, continually growing, and creative young person.

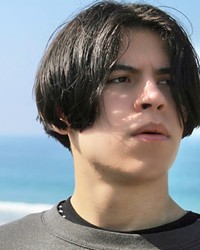

- Photo Courtesy Of Cindy Cruz-Sarantos

- CREATIVE SOUL (From left to right) Cindy Cruz-Sarantos remembers her son, Dylan Kai Sarantos, 18, as a young man learning to communicate his feelings through creative outlets.

He made his own clothing—he once fashioned a hoodie with spikes on it—created music, and wrote lyrics. Cindy said Dylan started the process of registering a trademark for his own clothing brand when he was 17.

On May 8, 2020, Dylan died of an accidental fentanyl overdose at the age of 18. His clothing trademark was officially registered on May 26, 2020.

Prior to his death, Cindy and her son lived on the Central Coast, but she decided to move her family to Southern California so he could receive care for his substance abuse disorder, bipolar disorder, anxiety, and depression.

Cindy is a registered nurse, but she took time off to focus her attention on helping her son. She took him to his substance abuse and alcohol counseling appointments and to his behavioral therapy sessions.

"He had been fighting really hard. He had a calendar where he would mark off the days of his sobriety," she said.

Xanax had been Dylan's drug of choice, Cindy said. It relaxes the body, but it's highly addictive.

"With substance abuse recoveries, it's a long haul, it's life-long. He had relapsed a couple of times, but he had changed so much in the year that he was with me in [El Segundo]," she said.

Cindy said his anxiety decreased, his communication with her improved, and he was able to focus more on his schoolwork and artistic hobbies.

"I got to have a really amazing kid. For a long time, without all of the anger and high anxiety he dealt with, I think he started to learn about himself and figure out what was best for him, but addiction is strong," Cindy said.

Cindy doesn't entirely blame her son's death on COVID-19, but she said it indirectly played a role in it. At the time, Dylan had been through almost two months of distance learning, not seeing friends, and not leaving the house. He was a busy person and being cooped up wasn't the best situation for him.

On May 8, 2020, Cindy found her son in their El Segundo home, unresponsive. She told New Times that she knew he was gone when she dialed 911. Looking back, she regrets not taking more time to say goodbye before the emergency response teams arrived.

After emergency responders took away Dylan's body, Cindy found his cellphone and discovered that his last virtual interaction was on Snapchat with a drug dealer. The social media app allows users to send messages, videos, and pictures to each other that can only be viewed once before the content disappears. She doesn't know how long Dylan had been communicating with the dealer; however, she did learn that Dylan purchased ecstasy from him.

She later learned through the coroner's report that Dylan took one ecstasy pill with traces of fentanyl in it and died.

Her son's death was ruled as an overdose, but that didn't make sense to Cindy because she didn't think her son could have overdosed from taking "just one pill." She spent several months watching her son's former drug dealer post his offerings on Snapchat, and she persistently presented her case to a Los Angeles County investigator—who is still looking into the case.

The Center for Advanced Defense Studies, a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit organization, reported that individuals were increasingly using the normal, open internet (not the dark web) to buy opioids directly from drug producers. It found that online transactions are made via encrypted messaging using payment tools such as Wickr, WhatsApp, or Bitcoin. The transactions between buyers and sellers are often concentrated on e-commerce websites, online chemical marketplaces, and social media.

"Additionally, many online synthetic drug sellers operate across multiple public platforms and maintain independent websites. Synthetic opioid sellers appear to use this collection of websites to cultivate a client base and ultimately direct traffic to a seller's own site to carry out transactions. Social media, particularly Facebook, has had an important role in creating these trusted networks of vendors and buyers," the nonprofit stated in a November 2020 report on synthetic drug networks.

The report emphasized that a majority of fentanyl trafficking comes from Chinese companies.

The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) stated in a 2019 report that the flow of fentanyl into the United States "is more diverse compared to the start of the fentanyl crisis in 2014."

According to the DEA, Mexico and China are the primary source countries for fentanyl-related substances trafficked directly into the United States.

San Luis Obispo Sheriff's Office spokesperson Tony Cipolla said its narcotics unit has found that most of the fentanyl coming into California is smuggled across the U.S.-Mexico border and is distributed or sold by narcotics traffickers.

"Fentanyl is here in [SLO County], and narcotics detectives are coming across it more frequently in searches during interdiction stops and locations where they have served search warrants. This can range from a couple of grams, an ounce or two, on up to a kilo," Cipolla said.

Sheriff's officers are also seeing fentanyl more frequently in overdoses and on traffic stops that could result in an arrest.

In 2020, SLO County Sheriff's narcotics and cannabis investigators seized 1,508 grams of fentanyl. The Sheriff's Office Narcotics Unit mostly deals with identifying local distributors who are connected to larger drug trafficking organizations either in the county or elsewhere, Cipolla said.

"It is our unit's goal to investigate and arrest the larger distributors of narcotics, thus slowing down the availability," he said.

Between 2016 and 2020, SLO County coroner cases of overdose deaths show an increase in those caused by fentanyl or an opiate that contained fentanyl.

In each of 2016 and 2017, the coroner's office ruled one death as caused by fentanyl. In 2018, there were two; 2019 reported nine; and in 2020, the coroner's office reported 15. In 2018, 2019, and 2020, the coroner's office reported traces of fentanyl in one, three, and 12 deaths, respectively, caused by a combination of opiate and meth use.

The report released in January had 80 cases where the cause of death and/or toxicology reports were still pending. Overdose toxicity is suspected in 25 of those deaths—which could include fentanyl, opiate, meth, a combination of opiate and meth, or multiple drugs.

In Dylan's case, the traces of fentanyl in one pill of ecstasy ended his life.

Cindy doesn't want her son's death to be labeled as just another overdose because he wasn't aware that fentanyl was mixed into the ecstasy that he took—she's sharing her story so parents can have a conversation with their children about this type of accidental overdose.

"We can't hide this. [I] am the type of personality that something happened to my kid and [I'm] going to try and save the next child," she said. Δ

Staff Writer Karen Garcia can be reached at [email protected].

Comments (2)

Showing 1-2 of 2