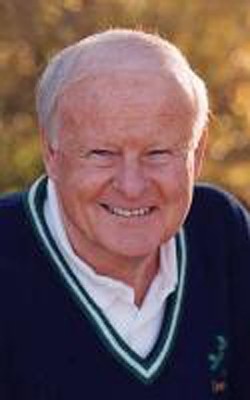

Al Moriarty spent the last few decades as the darling of the local financial services circle.

- PHOTO BY STEVE E. MILLER

- FIT FOR A KING : Moriarty’s mansion in Nipomo is a testament to the better times, pre-2008.

A homegrown small business success story, Moriarty rubbed elbows with city and county officials, attended fundraisers, and quickly ascended to the coveted list of Who’s Who in San Luis Obispo County.

All blue eyes and confidence, the 79-year-old, Teddy Kennedy-esque Moriarty, with his silver hair and vaguely East Coast manner, resembles everybody’s favorite Irish grandfather, someone to share a pint with while discussing the latest and greatest way to stay a step ahead of market trends.

During the peak of his career, Moriarty boasted an impressive clientele. His company, Moriarty Enterprises, also appeared to have the back of the little guy. By the early 2000s, a high percentage of his clients included people with very finite resources to invest: teachers, the retired, the elderly. If initial successes for his clients helped propel his reputation out into the community through word of mouth, his likeness and trademark four-leafed clovers peppering billboards and prominent advertisements in local media added to his notoriety.

An inductee to the Cal Poly Football Hall of Fame, Moriarty solidified his status as a charitable member of the community as well, coaching men’s football and basketball and donating handsomely to his alma mater.

He held and attended fundraisers and other events in swanky restaurants; Giuseppe’s in Pismo Beach was a regular haunt. He bought up valuable real estate and drove expensive Cadillacs.

His family is football royalty; his wife’s family co-owns the Pittsburgh Steelers, and two of his sons played ball at Notre Dame.

His brother-in-law was, until recently, President Barack Obama’s ambassador to Ireland.

Simply put, Moriarty had the appearance of a native son done good, and the look, capital, and clout to back it up.

But it was the high rates of return he promised clients through their investment annuities—historically at least twice the average return offered to those with low-to-mid-range resources by the big-name banks —that cemented Moriarty’s status as one of the top private financial planners in the county.

It was that high rate of return that eventually caught up with Moriarty in 2008.

Today, Moriarty sits in a self-imposed exile at his home in Bremerton, Wash., near Liberty Bay on Washington’s Puget Sound, combing through his ledgers, trying to figure out how it all went so wrong—and how he’s going to make his return to the Central Coast.

“I’m not run-of-the-mill. I’m creative,” Moriarty said in a recent phone interview with New Times. “And I’m going to win this thing.”

Against the advice of his attorney, San Luis Obispo-based Kirby Gordon, Moriarty talked at length with a New Times reporter on a number of issues—whatever came to mind, really: his recent financial troubles, the country’s financial troubles, football, and Ponzi schemes.

“They think I’ve been running a Ponzi scheme,” he said. “But Social Security is a Ponzi scheme. The Fed’s a Ponzi scheme.”

Bold and defiant, Moriarty claims allegations against him by former clients and his recent bankruptcy filing are par for the course in an industry heavily hit by the Great Recession. He’s not going down without a fight.

- PHOTO COURTESY OF CAL POLY

- THE MAN WITH THE PLAN : Al Moriarty—owner of Grover Beach-based financial services firm Moriarty Enterprises—filed bankruptcy in December in the face of 19 civil lawsuits and approximately $22 million allegedly owed to over 180 creditors.

But given the gravity of those allegations and his quickly dwindling pool of resources and friends, what began as a lawsuit here and there starting in spring 2012 seems to have snowballed into more than just a setback.

Since March, Moriarty has been hit with no less than 19 civil lawsuits from nearly 30 former clients and their trustees. He’s saddled with about $22 million in debt to his 180-some creditors. On the record, allegations against him range from breach of contract to fraud to elder abuse. Off the record, he’s been accused of trying to conceal his alleged fraud—and some people even question the apparently convenient timing of records going missing following a burglary at his Grover Beach office.

His business lost its accreditation from the Better Business Bureau. He dropped the membership with the local Chamber of Commerce. His license from the Department of Real Estate expired. And, though no criminal charges have been filed against him, law enforcement agents are keeping a watchful eye on him.

As he warned his clients he would, Moriarty filed for Chapter 7 bankruptcy protection in December 2012, effectively halting the lawsuits against him and giving him “time to organize.” Despite the fact that nearly all of the clients suing him live in SLO or Kern counties, Moriarty filed in bankruptcy court in Washington State, far from their direct scrutiny.

But he’ll prevail, as he always does, he told New Times with confidence, adding that he’ll soon return to SLO County after the whole thing blows over.

“I’m not running,” Moriarty said. “I had to get the hell away to think.”

In a community as small as SLO County, how does someone who’s ridden so high for so long fall so far, so fast?

‘Always thinking bigger’

“Personally, this hasn’t been easy,” Moriarty said. “But I’ve been through some tough times before, and I’m working my way through this.”

He began his business, then providing insurance, in 1954 while he was still a junior at Cal Poly. Even from that early date he was a well-known member of the community, having been on the roster during the Mustangs’ undefeated 1953 football season, primarily as a tackle. Known for his versatility, he occasionally did stints as a guard, kicker, and even quarterback, as well as playing on the basketball team under legendary coach Ed Jorgensen, according to the university.

By his own admission, contacts and friendships made through his connections with the university would prove invaluable.

He graduated in 1957, and though he was devoted to developing his company, Moriarty continued to give back to his alma mater’s athletics department, as well as coach football and basketball for Mission College Prep, volunteering as that school’s athletic coordinator for 10 years.

- PHOTO BY STEVE E. MILLER

- BREACHED : Some people suspect that a break-in at Moriarty’s former office in Grover Beach was an inside job, which Moriarty himself denies.

He was inducted into the Cal Poly Athletics Hall of Fame in 2002.

Sports continued to play a major role in his life well after his educational career ended. He married Patricia Rooney, a member of the same Rooney family that’s owned a majority share of the Pittsburgh Steelers since the team’s 1933 formation. Al and Patricia had five children together, including two sons, Larry and Kerry Moriarty, who each played for Notre Dame. Larry would later play professionally as a running back for the Houston Oilers; Kerry, now in construction in Montecito, may have had a promising athletic career had he not run second-string to a young quarterback named Joe Montana.

In the 1980s, as Moriarty continued to establish his name as one of the county’s premier financial consultants, he began investing heavily in gold.

“When I went into gold in the ’80s, people laughed at me,” he said.

He secured a $2 million line of credit from local banks, which he backed with his gold assets. Around that time, he said, he began changing his investment portfolio and started steering away from traditional mutual funds.

“I’m not a stock guy because I think the market’s crooked as hell,” he said. “It’s the big guys that make the money. The little guys are just pawns.”

In the early ’90s, Moriarty said, he developed a formula that promised his clients a fixed 10 percent return on their investments with him. Though he declined to go into detail with New Times on how he was able to provide this return across the board, he did say that clients saw great returns after issuing him loans—enough to pay their monthly expenses and have a little profit left over to do with as they pleased.

He told New Times he used many of those loans to create 403(b) retirement plans for former teachers and people in the health-care industry, helping them buy homes and helping seniors make the most out of their retirement.

“I’m good at what I do, and people knew it,” he said. “I made them a lot of money.”

And though he would later report that he only earned about $85,000 a year, Moriarty amassed an impressive collection of properties in SLO County and Washington State, as well as vehicles and other perks.

He had an office in downtown Grover Beach, a million-dollar mansion in the Nipomo hills, acres of land near a prominent vineyard, and a number of condos, not to mention two Cadillacs and a Dodge Ram van.

“I was always thinking bigger,” he said.

But 2008 changed all that.

- Moriarty Enterprises slogan

- ‘INTEGRITY, AS IN NATURE, WILL ALWAYS BE SUPREME.’:

According to Moriarty, a combination of factors during the economic downturn—especially the tanking real estate market—critically wounded his investments. Soon, the banks pulled his credit lines. And because most of his hard cash was tied up in non-liquid assets, Moriarty began defaulting on his payments to clients, one by one.

What began as a warning letter here and there turned into a list of civil suits. By July 2012, he was facing seven suits. By November, it was 19.

His attorney successfully argued to consolidate the lawsuits into one. But that didn’t stop the bleeding. In December, Moriarty filed for bankruptcy.

“If they would have just stayed with me, I would have been able to work through it,” Moriarty said of his litigious clients. “They’re not using their heads.”

On Dec. 31, 2012, Moriarty’s bankruptcy attorney, Marc Stern, filed on his behalf in Bankruptcy Court in the Western District of Washington, though the bulk of Moriarty’s assets—not to mention most of his creditors—are in SLO County. A trustee, Bainbridge Island, Wash.-based Michael Klein, has been assigned to Moriarty’s case.

Neither Klein nor Stern returned requests for comment.

The bankruptcy accomplished two things. It bought Moriarty some time; by law, all civil proceedings and attempts to collect on debts are stayed until a ruling. The filing also gives Moriarty time to liquidate some of his remaining assets. He recently sold off some of his gold and is currently trying to sell roughly 31 acres of land near Laetitia Vineyard in Arroyo Grande worth some $1.5 million, he told New Times.

“It was painful, but it also stopped the hemorrhaging to where I can think this thing through,” he said.

In his filing, Stern lists Moriarty’s assets at nearly $4 million in property in the South County, as well as his home in Washington State. He is, however, trying to keep his Washington home (which he valued at $325,000), his three vehicles ($21,000 in total, including a 2008 Cadillac DTS valued at $12,000), about $5,000 in household goods, and about $1,500 in jewelry.

‘Borrowing from Peter to pay Paul’

“I just can’t understand how he got people to loan him that much money,” San Luis Obispo-based attorney David Kraft, who is representing three of Moriarty’s alleged victims, told New Times.

The economic downturn exposed a number of undercapitalized investment operations in SLO County, the most notorious of which was Karen Guth and Joshua Yaguda’s now-defunct Estate Financial. Guth and Yaguda pleaded guilty to 26 felony counts in 2009 after collecting millions from investors in real estate-backed securities and losing it amid allegations of fraud.

While there’s been suspicion of wrongdoing in Moriarty’s case, he denies it and nobody’s filed any criminal charges; his unhappy former investors have been pursuing him in civil courts.

Marilouise Mullens and her late husband Robert were living in a mobile home park in Oceano in March 2006 when they first sought advisement from Moriarty Enterprises. According to a lawsuit filed in September by their attorney, Roy Ogden, Moriarty initially convinced the couple to invest $80,000 with him at 10 percent interest, to be paid back monthly over five years; essentially, Moriarty was receiving a private loan from the Mullens. But as stipulated on the promissory note he issued them, the full amount plus interest would come due upon default of payment.

In August 2006, the couple again issued Moriarty another loan, this time in the amount of $120,000 at 10 percent interest. Then again in March 2008 for $263,500. Over the next three years, the couple would go on to invest nearly a million dollars with Moriarty.

Robert passed away in December 2011, and Marilouise, 87, is fighting cancer and dementia and has since moved into a care facility in Bakersfield near her daughter, who has taken over her affairs. According to Ogden, Marilouise has lost a significant portion of her retirement, to the tune of some $255,000.

But her lawsuit alleges more than simple breach of contract; Ogden further accuses Moriarty of fraud, concealment, constructive fraud, and elder abuse. Ogden wrote that Moriarty “intentionally targeted elderly persons” with a “Ponzi-type scheme by [Moriarty] to keep [his] business afloat by borrowing from Peter to pay Paul.”

Moriarty attorney Kirby Gordon countered, as he would against several of the other lawsuits, that the case should simply be about breach of contract.

In “what should be a straight breach of contract action,” Gordon wrote in a November 2012 demurrer, Ogden “has attempted to stretch this straight-forward promissory note case into financial elder abuse by alleging that the non-payment of the note was somehow actionable fraud.”

“These people have no ability to re-earn that money. They need that now in order not to be a burden on the state or on their children,” Ogden told New Times. “It’s really sad as a lawyer; you almost feel helpless because when he says he’s so upside-down and he files [bankruptcy].”

Bay Area attorney Anne Marie Murphy is representing 70-year-old Moriarty investor Martha Olt, a retired teacher living in San Miguel. Like Ogden, Murphy’s accusing Moriarty of operating a Ponzi scheme, among other claims.

According to Olt’s lawsuit, filed in August, she was allegedly told that her money—invested for a seven-percent return—would be used to make mortgages for retired school teachers. In September 2011, she loaned Moriarty $282,105—most of her retirement savings, according to her lawsuit—which was to be repaid with 10 percent interest over the course of 60 months, in addition to a $5,000 “bonus” for making the loan. Murphy called the transaction “entirely inappropriate” for her client.

According to Murphy, Moriarty immediately missed the first payment; he made two subsequent payments, then stopped altogether, and allegedly began dodging Olt’s calls. Olt has received nothing since December 2011, Murphy said.

“Our client was led to believe that she was lending money to school teachers,” Murphy said.

Olt has since returned to work as a substitute teacher to try to replace at least some of what she lost with Moriarty.

“These are people that could ill afford to lose their savings,” Murphy said.

Most other lawsuits against Moriarty also allege that he was targeting the elderly. A lawsuit brought by Arroyo Grande resident Anthony Azevedo on behalf of his 81-year-old mother alleges that Moriarty showed up at Daisy Hill Estates, a senior mobile park in Los Osos, to conduct a “seminar with old folks” on investing. Calls to the park’s management for comment weren’t returned.

But whether or not he sought out seniors as clients, the question that could make the difference in a criminal case is simple: Did Al Moriarty intentionally defraud his clients? His attorney argues no. In fact, in response to one of the lawsuits, Gordon wrote that Moriarty is 79 years old and “prone to confusion and loss of memory.”

But not everyone’s buying that defense.

“I would say that Gordon and his client are in denial. If you look at the scope of what Moriarty did, he was apparently targeting a class of people generally unable to make those kind of decisions. They saved their money because they were from that generation that knew how,” Ogden said. “[Moriarty] either knew or should have known he wasn’t going to be able to repay all of these people.”

Ogden believes the way Moriarty invested his money didn’t create the cash flow needed to fulfill his obligations.

“Then when he ran out, he borrowed more,” Ogden alleged.

Moriarty acknowledged that he’s been in contact with the FBI, and told New Times that investigators—though he wouldn’t say from which agency—served a search warrant at his office.

“Everything’s not going to be OK, it’s clear,” Ogden said. “He’s trying not to look bad in the press, but it’s over.”

And then there was the office break-in. In a deposition included in the court file before SLO-based attorneys Kraft and John Sachs, Moriarty explained, on the record, exactly how he operated his business, and let slip a few pieces of information that have raised eyebrows.

“What did you do with the money that you got from [Floyd Cannon, the first former investor to file suit]?” Kraft asked Moriarty on Nov. 7, 2012, a month before Moriarty filed for bankruptcy.

“It doesn’t make any difference what I did with it,” Moriarty said, according to a transcript of the deposition. “It’s a loan. I can do whatever I want with it.”

Kraft asked him about his assets.

“They’re all encumbered. I have nothing,” Moriarty said. “If they force me into bankruptcy, nobody gets nothing. And I’m not trying—I don’t want to go there.”

Asked about how he specifically made payments to his customers, Moriarty said that when money came in, he put it in the “general pot” and used it according to what he needed to pay at that particular moment.

“Would that be to pay other people’s loans?” Kraft asked, to which Moriarty replied, “Sometimes.” When asked how he used Kraft’s clients’ money, Moriarty replied, “I don’t know what I did with it at the time. I mean, you know, it’s nebulous.”

Moriarty told Kraft that “90 percent” of his clients were continuing to work with him, and those who weren’t were the ones who needed the monthly payment from him to pay their mortgage or rent at their assisted living facility.

“So, in a case like that, I rob Peter to pay Paul to get the money to them,” he said, according to the transcript.

When asked about how he kept records of his transactions, Moriarty told Kraft that a number of his ledgers and records were missing following a burglary at his office on Aug. 29, 2012.

According to a Grover Beach Police Department report, officers responded to a report of a break-in by one of Moriarty’s commercial tenants who shared the building with Moriarty Enterprises.

According to the tenant, it appeared someone entered the building with a key and ransacked the interior, making off with a laptop, a printer, and some additional keys. She noted, however, that several items of value had been left untouched.

Officers interviewed Moriarty about the burglary. He reportedly told them the building has no video surveillance, and he never bothered to activate its alarm system. He added that his assistant and he were the only two people with a master key to the building. According to the report, Moriarty didn’t mentioned any ledgers or files to investigators among the missing property. He would later tell Kraft that the thieves “stole everything on all my people,” including computers, faxes, and copy machines.

Moriarty told police that he suspected a disgruntled former employee in the burglary; officers have made no arrests, and the investigation has gone cold pending any more evidence, according to the department.

Moriarty told New Times that he had nothing to do with the break-in, and though he said he knows who did it, he declined to elaborate.

“They’ve got a witch hunt on me, particularly my competitors,” he said. “It goes with the territory. There’s a lot of jealousy when you’re successful. People will get jealous and try to bring you down.”

The long road to recovery

Because of his ongoing bankruptcy case, the civil proceedings against Moriarty remain at a standstill. And many residents are left wondering why, in a case with so many former clients echoing similar allegations of criminal acts, Moriarty isn’t facing criminal charges as well.

Steve von Dohlen, financial crimes investigator for the SLO County District Attorney’s Office, said that investigating possible financial wrongdoing isn’t always a clear-cut endeavor.

Unlike the Estate Financial case, von Dohlen said, which was criminal in nature even before victims of the hard money lending scheme took the perpetrators to court, Moriarty’s case involved civil complaints piling up in advance of investigators being hip to the situation.

“This case is a good example, where [Moriarty’s] investors realized they were ending up on the short end, and … individual victims file civilly long before our agency or other agencies even figure out there’s something amiss,” von Dohlen said. “By that time victims may find out there’s 10 other suits out there, and then there’s that critical mass where they say, ‘This is bigger than me’ and contact law enforcement.”

Von Dohlen told New Times that in typical white-collar crime cases, an alleged victim will usually file a report with a local law enforcement agency such as a municipal police department, which will in turn conduct an investigation and determine whether to recommend charges to prosecutors. His office will then work with other agencies such as the California Department of Corporations, the Department of Real Estate, and the Department of Insurance—sometimes even with the FBI.

“In some cases there may be multiple complaining parties in different parts of the state, and we find that having the assistance of these state agencies tends to do a better job of getting them all together,” he said.

But just because charges haven’t been filed against Moriarty doesn’t mean he’s out of the woods. Von Dohlen wouldn’t confirm or deny whether the DA’s Office ever had, or is continuing, an investigation on Moriarty Enterprises. Neither would the Securities Exchange Commission, nor the Department of Corporations, nor the Department of Real Estate, nor the FBI.

“This may seem redundant, but with our burden of proof, there is a thorough approach we have to take,” von Dohlen said. “Folks can look from the outside and ask, ‘How can that not be a situation where we get involved?’ And the best answer is that there may or may not be charges, but that’s just not the position where we’re at.”

Cases of this magnitude can also require investigators to work backward in re-creating decades’ worth of transaction records.

“This is not a situation where we want to rush into it headlong to where it causes a problem with the case later,” he said. “Cases like these can, unfortunately, take a long time.”

In a situation where everybody’s trying to recover their money, even if the civil lawsuits are successful after the bankruptcy process, the plaintiffs could then face a chaotic and lengthy ordeal of dividing up Moriarty’s assets—if any remain.

Von Dohlen said that, for now, situations like these appear to serve that old adage: If something seems too good to be true, it likely is.

“You should never invest money you can’t afford to lose,” he added. “And a person should be wary if they’re told they have nothing to worry about.”

Whether Moriarty ever faces a judge in a criminal case, one thing is certain: Given his bankruptcy protection, it’s unlikely his clients will ever be fully compensated. But despite his mounting troubles, Moriarty has no problem stating on the record that he has done nothing illegal and will come out of the situation with his good name intact.

“I’ve never lied in my life,” Moriarty said. “When the time comes, I’ll tell the whole story.”

His bankruptcy hearing is scheduled for July.

Staff Writer Matt Fountain can be reached at [email protected].

Comments