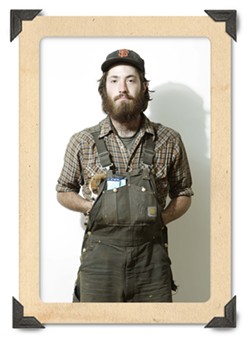

- PHOTO BY STEVE E. MILLER

- CHRIS TRAYLOR : On the road for a year and eight months, Traylor says he’d like head to the hills of Oregon to become an organic farmer, or possibly a brewer.

They tromped down San Luis Obispo’s Osos Street the other day like a troupe of arthouse clowns, maybe 15 in all. They were so dirty it could have been a shift change at a countercultural coal mine. There were dogs of all sizes on hemp-rope leashes, sticker-strewn guitars carried by their necks and strung over shoulders like baseball bats. They had dirty Carhartt pants and anarchy symbols on their shirts and combat boots and dreadlocks and tattooed faces—everything you’d want from such a tableau and more. There were little ones, big ones, brown ones, blue in that parade of societal cast-offs and castaways.

Where, you couldn’t help but wonder, were they going? And what do they do? And how do they get here? And where do they sleep? How do they travel with those dogs? And do they feed those mongrels?

More importantly: Are they the victimized faces of the new economy or just kids hooked on responsibility-free living and the romance of the road, who have warm beds to snuggle into whenever they tire of their juvie adventures?

I engaged one of them, a scrawny and oh-so-young Arlo Guthrie-faced kid whose name I never got or sought. What’s going on? I demanded of the waif. His eyes weren’t perfectly focused, but he was quick and engaging and he spun out an enticing tale of hopped trains and new frontiers and, as he gestured wildly at the surrounding green hills to emphasize the beauty of the world, his guitar smacked a blue-shirted businessman passing by on the sidewalk. The kid said ‘sorry,’ but his eyes twinkled in a way that made me think he wasn’t.

Yeah, yeah, but why were they all here—right here—now? I asked.

“Don’t you know about the circuit?” he wondered. I didn’t, so he told me a story about a street-kid circuit, or “the hippie trail:” a squatter-friendly chain of towns from New Orleans to Los Angeles to Santa Cruz to Berkeley to Portland to Eugene to Seattle to Chicago to wherever, connected by freight lines, and reputations as party spots and counter-cultural vibes. He said San Luis was just a logical stutter stop as street kids, like the swallows whenever they’re fed up with Capistrano, make their way back north.

He said he was from Connecticut and had been on the road since he was 15; he looked like he was still 15.

Days later, a colleague told me a story of the son of a friend who’d picked the most amazing hitchhiker, a kid from Connecticut, who’d been on the road since he was 15. This kid gave the other kid a ride and, I’m told, came away infected with the spirit of the road.

- IS IT ILLEGAL TO BE HOMELESS?: A: No, but in the City of SLO, it’s illegal to: • Stay on a bench for more than an hour • Sleep on a bench • Put a backpack on a bench, taking up a seat • Obstruct the sidewalk • Panhandle “aggressively.”

There’s a problem in San Luis Obispo. A transient problem. It was featured on the news the other day on one of the localish television stations. And the problem isn’t the local homeless population, those faces people have grown used to seeing, who in some cases may be old high-school classmates. Instead, the problem is this latest influx of street kids: lots of them.

Leaders of SLO’s Downtown Association grew alarmed by complaints from local business owners about dirty young folks and their dogs occupying benches and intimidating shoppers with their panhandling, even locking themselves in bathrooms and smearing feces on the walls. They asked for a meeting with San Luis Obispo Police.

Lt. Steve Tolley, day watch commander with the SLO Police Department, attended the meeting the other day along with some fellow officers. He left pledging to increase foot patrols in the downtown area. By that evening there seemed to be more police out talking to street kids at Farmers Market. Such complaints, Tolley said, ebb and flow.

“It was similar to this a couple of years ago, where there seemed to be an increase in the

younger homeless.”

He confirmed the feces-smearing incident, but said for the most part, the concerns have simply been that there have been so many young vagabonds lately, and store owners and shoppers don’t like it. He said there’s not all that much the police can do. The latest batch of street kids haven’t been doing much drinking in public, something that can get them arrested.

Instead, they’ve been hanging out, in the parks or on benches. In San Luis Obispo, it’s illegal to sit on a given bench for more than an hour or to put one’s backpack on the bench and it’s illegal to block traffic on the sidewalk, and it’s illegal to panhandle “aggressively” and it’s illegal to sleep on the bench. But apart from those restrictions, it’s not illegal to be hanging out, young or old, ugly or pretty.

“I want my guys to be respectful, to go by the law and abide by the Constitution,” he said. “That’s what makes it a challenge at times. We have rules we have to work within, and a lot of times nobody’s committing any crimes … We’re looking for cooperation and I think we’re going to get that cooperation if we treat people right.”

If there’s an invasion of street kids, however, it isn’t necessarily being tabulated by the social service network. A representative of the Prado Day Center, where SLO’s homeless can get services and a lunch, said there has been an increase in people seeking help, but not from folks he’d categorize as street kids.

And, in general, the travelers don’t make up a large segment of the ranks of local homeless people. According to a 2006 count of the homeless in SLO County, about 20 percent had lived in the area less than a year, and just three percent said they had been in the area for less than a month.

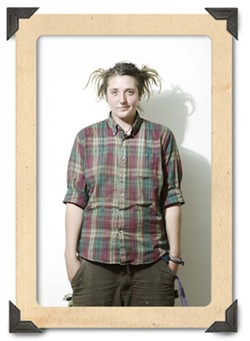

- PHOTO BY STEVE E MILLER

- ASHLEY : Ashley is from a small town outside of Eugene.

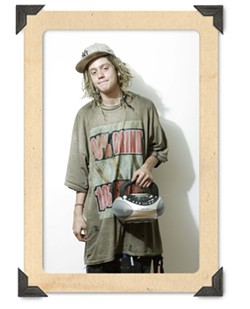

Eric Palencia would like it known that he isn’t looking to rob folks. Chris Traylor wants it said that, yes, he feeds his dog. And Ashley, who didn’t want her last name used, hopes people know that it sure would help if they could give them all a ride when they’re hitchhiking.

The trio of traveling companions were lounging on the sidewalk between the Gap and Express in SLO on a recent day, rolling cigarettes, listening to jazz on a little boombox, playing with a four-week-old puppy named Rastus, and generally providing a vivid contrast to the Gap store window display above their heads, which advertised “The new button-down.”

On a sunny February day, when the rains were at bay and the temperature climbed to nearly 70 degrees, it seemed a fairly idyllic existence. And it can be great, said Palencia, an 18-year-old painter and musician out of Chicago who said he has been on the road for about four years, since he faced becoming a ward of the state. But, he said, it can also be a fairly tough lifestyle.

The complaints? Walking 30 miles in a day. Sleeping outside occasionally—he tries hard not to. In the past, there have been irresistible temptations with drugs. Then there’s this:

“I’m seriously tired of getting hassled,” he sighed. “I know it’s a serious economic downturn, but we don’t have to turn into a police state, you know?”

He said SLO has been fairly hospitable, but crowded. He and his companions had only been in town for a few days, but in those days he said he noticed at least 20 other street kids—he calls himself a squatter punk—and watched as some got drunk and made trouble in local businesses. That same feces story came up. That made life harder on everyone, he said.

I asked him about the circuit the other kid had mentioned, and he agreed there is one, sort of, anyway.

“It’s kind of like a huge game of musical chairs, but instead of chairs it’s cities and instead of kids at a party, it’s squatters.”

The trio hoped to head to New Orleans next. Just after they headed to the feed store to get shots for Rastus. That’s right, shots for the dog.

Traylor, a 21-year-old guitarist wearing overalls and a beard who dreams of starting an organic farm in the hills of his home state of Oregon, said one of the favorite comments he gets—often shouted at him from cars that slow but do not stop—is: “You know you’ve got to feed those dogs!”

“I tell them, ‘No, we just fill them with gasoline and set them on fire!’” He says this as he strokes the head of Rastus, who is curled contentedly inside his overalls.

To get to New Orleans, they say they plan to start the trip on the train, dodging trainyard bulls as they clamber into open freight cars. Their other dog, Monoose, they boast, even knows how to climb the ladders. Why New Orleans? “You can’t really go hungry in New Orleans. Or stay sober,” says Ashley, a 19-year-old from a small town outside of Eugene.

Elsewhere in the conversation, though, Palencia acknowledges that there are lots of ways to get around, and trains aren’t always the most convenient. Lots of people have cars, and everybody has thumbs and feet. Besides that, there’s Greyhound, and since Monoose is a registered service dog for Traylor—he has epilepsy and a body he says has been bruised by too many years of skateboarding—he can ride along legitimately.

The story’s similar when it comes to sleeping out of doors. They don’t say where they’ve been sleeping, but emphasize that nobody—nobody—likes to sleep under a bridge, and they rarely do. As for food, the three say they live mainly off of the fat of the land, often Dumpster diving for meals. And, while they say they don’t panhandle, Traylor says he often plays his guitar for money, something police are often more tolerant of than begging.

Lt. Tolley said many kids have been squatting in some of the abandoned buildings around town. One spot that police are paying attention to, he said, is the former home of Central Coast Surfboards on Higuera, which is now vacant. He said police have been stepping up patrols of abandoned buildings in response.

- PHOTO BY STEVE E. MILLER

- ERIC PALENCIA : Originally from Chicago, he’s been traveling for about four years. He’s 18 and originally hit the road to escape becoming a ward of the state.

If the street-kid lifestyle doesn’t carry a whiff of romance for you, it’s possible you’re not 14, or in a tough situation. There are websites that glamorize the life. One of them is CrimethInc.com, a self-described “decentralized anarchist collective” that publishes books, blogs, and music that celebrate an anti-consumerist, live-off-the-fat-of-the-society lifestyle. Its flagship book is called Days of War, Nights of Love. The authors advise: “Remember, the destructive impulse is also a creative one … happy smashing!”

Those were the kinds of notions that originally enthused Palencia for a life on the street, although he also said he was escaping becoming a ward of the state. But he said the punk ethic of destruction and anarchy, once strong, has largely faded.

“I used to be really nihilistic before I started thinking about wider social issues.”

Such stories supply a continuing cycle of new street kids onto the circuit. Traylor, who says he’s been traveling for about 18 months, says many younger kids are simply not prepared for the lifestyle. The trio ended up in Salinas weeks ago, and not by choice. He said they were jailed for illegal camping and their dogs were sent to the pound. Then they were released, in the middle of the night, with nothing in the middle of nowhere. There was no romance in the life that day.

Still, Palencia smiles a goofy grin when asked if he’s happy. He is, he says.

“Every day I wake up is a good day.”

Managing Editor Patrick Howe can be reached at [email protected].

Comments