Editor's note: This article was produced as part of a Data Fellowship with the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism.

Jamie Maraviglia has spent long days and nights in the hospital, but her time at home with medical bills is sometimes even more intense.

- Photo Courtesy Of Jamie Maraviglia

- HOSPITALIZED Arroyo Grande resident Jamie Maraviglia says that the hospital bills for her daughter, Ara (pictured), who suffers from a chronic illness, are putting significant financial strain on her family.

The Arroyo Grande resident is routinely in and out of the hospital with her 2-year-old daughter, Ara, who suffers from Hirschsprung disease, a chronic intestinal illness.

Ara started out her life in the neonatal intensive care unit at Sierra Vista Regional Hospital. She's had four surgeries since, and is "gearing up for more," her mom said.

"I have stacks and stacks and binders of medical billing," Maraviglia said. "I would spend, at one point, 10 hours a week on the phone with insurance, with hospitals, with billing companies. A lot of it is just arguing."

Even with her employer-sponsored health insurance, Maraviglia said she's astonished by the amounts on her bills—the charges, the out-of-pocket costs, the confusing network limitations, and her ever-rising insurance premiums.

Maraviglia believes that getting health care on Central Coast is even more expensive than in other places. She's identified a core underlying reason why.

"We live in a health care desert. There's no other way to say it," she said. "We are basically beholden to two major health care companies."

Tenet Healthcare and Dignity Health—a national for-profit and national nonprofit hospital system, respectively—own all five hospitals in SLO County and Santa Maria as well as a network of local outpatient services, clinics, and physicians.

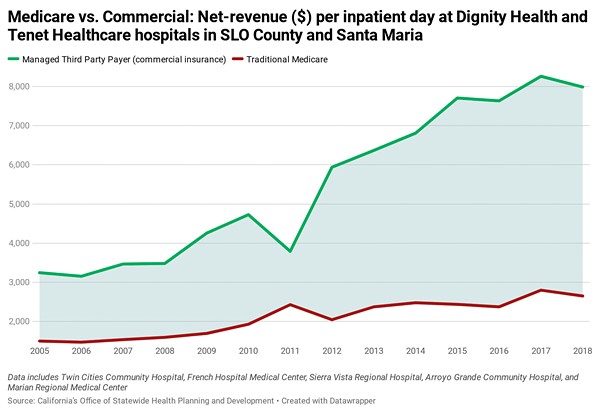

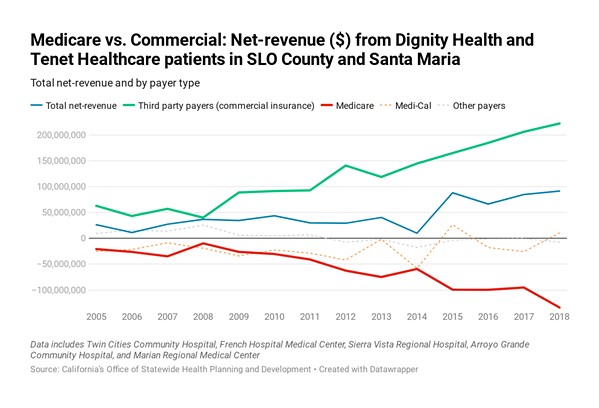

According to a New Times investigation of the cost of local health care, the two systems made three times more revenue on third-party payers—like Maraviglia on an employer-sponsored plan—than they did on Medicare patients in 2018 on a per-inpatient day basis, according to California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development data.

Between 2005 and 2018, local hospitals' net revenue on inpatient and outpatient commercial payers grew 354 percent, to $222.1 million, while their net losses on Medicare payers plummeted 641 percent, to negative $133.8 million.

Locals and health care experts told New Times that the larger, highly integrated systems are using their market leverage to receive higher reimbursements from private insurance providers, which they say raises the overall cost of health care and causes anticompetitive impacts.

"It dramatically raises the cost of doing medical care," said David Palchak, an Arroyo Grande-based oncologist with his own independent practice. "I can't get anything above Medicare rates [from commercial insurance]. ... Two to three times Medicare is unreasonable."

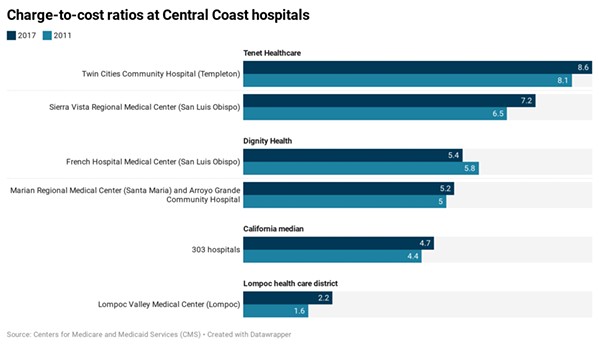

In 2017, the five hospitals set their prices between five- and nine-times higher than what Medicare determined their costs to be—bigger markups than most hospitals in the state, according to Medicare data. Dignity and Tenet officials declined to answer specific questions about their prices and revenue trends, but they touted the benefits of integrated care systems.

- Source: Centers For Medicare And Medicaid Services

- MARKUPS A charge-to-cost ratio "is a way to measure the markup of chargemaster rates over Medicare-allowable costs. It's a hospital's total gross charges divided by its total Medicare-allowable cost," according to Johns Hopkins University research. While raw chargemaster rates are not often billed to patients, they are often the starting points for reimbursement negotiations with insurance providers, industry experts say.

"Our primary goal is to provide seamless care and service between our hospitals and our clinics, imaging centers, and urgent care facilities, for the patients we treat every day," Tenet Health Central Coast CEO Mark Lisa said in a statement. "[Tenet] provides safe, first-class health care to anyone who walks through our doors. ... As the largest private, non-utility, employer in SLO County, we are proud to provide services to the communities we are part of."

Consolidation concern

In recent years, health care researchers, advocates, regulators, and lawmakers have all discussed hospital consolidation with increasing concern and urgency.

Earlier this year, Sen. Bill Monning (D-Carmel) introduced Senate Bill 977, which would expand the state attorney general's oversight of private health care transactions. In 2019, California Attorney General Xavier Becerra sued Sutter Health over its allegedly anticompetitive charging practices, which ended this year in a $575 million settlement for Sutter to pay.

According to a 2018 study at UC Berkeley, more than 80 percent of California counties, including SLO and Santa Barbara, had hospital markets that were "highly concentrated"—or close to becoming monopolies.

This consolidation is a result of years and years of both horizontal (such as a hospital acquiring another hospital) and vertical (such as a hospital acquiring a physician group) integration, experts say. Many researchers conclude that the consolidation wave has driven up health care costs.

"The data is incredibly clear on this," said Jaime King, a professor at UC Hastings College of Law who specializes in health care markets and policy. "Hospital mergers result in significant price increases almost immediately. Both entities' prices go up as a result. Neighboring hospitals' prices go up, too, as a shadow effect. It's having an even bigger effect in the overarching market."

- Photo By Jayson Mellom

- ONE-STOP SHOP Tenet Healthcare, a Dallas-based for-profit hospital owner, operates Sierra Vista Regional Medical Center in SLO, Twin Cities Community Hospital in Templeton, and a network of outpatient facilities.

In SLO County, Tenet and Dignity's dual share of the in-patient hospital market began in 2005, when Dignity (then Catholic Healthcare West) acquired a struggling French Hospital Medical Center and Arroyo Grande Community Hospital from previous ownership. It already owned Marian Regional Medical Center in Santa Maria. Tenet had owned Sierra Vista Regional Medical Center in SLO and Twin Cities Community Hospital in Templeton for years prior.

In the 15 years since, the two systems expanded. Tenet bought a multi-state hospital chain, Vanguard Health Systems, in 2013 and then partnered with outpatient giant United Surgical Partners International. In 2019, Dignity merged with Catholic Health Initiatives, a Colorado-based hospital chain, to form CommonSpirit Health, which is now the second largest nonprofit hospital owner in the U.S.

As the systems grew outward, an increasing number of Central Coast physician groups, primary care centers, urgent cares, and other outpatient services joined Tenet and Dignity's umbrellas.

"That's where a lot of the growth is now focused," King said.

Prices at the SLO County and Santa Maria hospitals vary by facility, but in 2017, all five hospitals' chargemaster rates, when compared to their Medicare determined costs, were above the state median.

Chargemaster rates (the raw prices for all services, goods, and procedures) are rarely what patients and insurers end up paying for care. But they're often the starting point for negotiations with insurers and for other billing calculations.

"They are relevant," King said, "because oftentimes insurance companies negotiate a percentage off of the chargemaster. And they'll say, 'We negotiated 50 percent off the chargemaster.' But what is the chargemaster? If the chargemaster is 500 percent of Medicare, that's still 250 percent above Medicare."

On average, California hospitals' chargemasters were about five times their total costs as calculated by Medicare (called a charge-to-cost ratio). Locally, those charge-to-cost ratios ranged from 8.6 at Twin Cities Community Hospital, down to 5.2 at Marian Regional Medical Center and Arroyo Grande Community Hospital.

Medicare vs. commercial

Across the state, one evident trend shows up in annual hospital financial reports: Hospitals are making increasing revenue on third-party payers (commercial insurance patients) and less revenue on Medicare payers.

Viewpoints on this development vary. Critics of hospitals say they are simply price gouging commercial insurers to make more money. Hospitals, though, argue that Medicare has failed to keep up with their expenses. Others say the hospitals are simply spending too much, and now they have little choice but to charge the groups they have control over.

"We have this unbalanced system," said Jay Gellert, the former CEO of Health Net insurance, "where these guys really do have to chase the limited number of commercial patients in order to be economic."

Gellert was part of an insurance industry team in 2010 that assisted the Obama administration with the development of the Affordable Care Act. He said while the act gave insurance to many Americans, it left the door wide open to more consolidation.

"They basically encouraged consolidation of hospitals, hospitals buying up physician practices, the theory of integration, but there was no accountability behind it," he said. "They had no cost containment in the system."

Gellert said the consolidation phenomenon is inherently anticompetitive.

"Just like in much of America, companies have learned that true competition is hard, and it's a lot easier to consolidate and have some ability to limit price competition," he said.

Palchak, the independent oncologist in Arroyo Grande, said he experiences those anticompetitive effects firsthand. Every year, he writes to Blue Cross and Blue Shield to make an offer: If it paid him 30 percent above Medicare rates, it would allow him to grow his practice and expand services throughout the community, while saving the patients and health plans money. He's yet to receive a response.

"If they would contract with me at this rate I could provide all cancer care for the community as I would have enough money to expand throughout the region," he said.

Hospitals oppose legislation, defend mergers

While some Californians call for major national health care reform, like Medicare for all, which would wipe out the private insurance market, state lawmakers have tried to put forth more nuanced legislation aimed at controlling health care costs.

Assembly Bill 3087, which was proposed last year but killed, would've established a commission to oversee and put ceilings on the payments paid to medical providers by commercial insurers.

Sen. Monning's SB 977—introduced right before COVID-19 hit—would empower the Attorney General's Office to review for-profit hospital mergers and acquisitions under certain circumstances. Currently, the attorney general does not have purview over those private sector health care transactions, only nonprofit ones.

"There have been some market manipulations that have been anticompetitive," Monning told New Times. "SB 977 would give the AG [attorney general] oversight authority on certain designated transactions simply to review and make sure patients are protected. ... It's not going to shut down an ER."

Tenet Healthcare is among the hospital players, including the American Hospital Association, to come out against the bill. In a July 2 letter to the state Assembly Health Committee, the company's four California CEOs said the bill "would create a presumption that these transactions are anticompetitive, ... creating a 'guilty until proven innocent' system."

"There are many reasons hospitals merge or affiliate," the CEOs wrote, "including to preserve and expand access to care across the communities they serve, introduce new services, coordinate and integrate the delivery of services, create centers for excellence for complex procedures, better support nurses and physicians, and more."

The executives said the bill would hamper hospitals' mobility as they struggle with COVID-19 and its fallout.

"The timing for SB 977 couldn't be worse, as California hospitals of all sizes are already struggling under the enormous strain and financial impacts in meeting the generational challenges associated with the COVID-19 pandemic," the letter read. "Such mergers, affiliations, and related transactions can be not just timely, but vital to preserving a safety net and access to care for residents of these particular communities."

Monning countered that the instability created by COVID-19 makes his bill even more important.

"The opposition said now with COVID-19 and the economy in distress this really isn't a good time to do this. My response is just the opposite," he said. "Because of COVID-19, you have some systems that are in economic distress and could be susceptible to a large hedge fund that could see an opportunity to make a quick, below-market acquisition without any commitment to the local community."

- Photo By Jayson Mellom

- INTEGRATED Dignity Health owns French Hospital Medical Center (pictured) in SLO, Arroyo Grande Community Hospital, Marian Regional Medical Center in Santa Maria, and a variety of local clinics, services, and physicians. Its new parent company, CommonSpirit, is one of the largest nonprofit hospital systems in the U.S.

King, the law professor at UC Hastings, echoed Monning's concern.

"COVID-19 has put a massive strain on small hospitals, on physician practices," she said. "People are going to the doctor less. The remaining independent entities are looking at either closing their doors or selling to a big hospital system that's going to allow for an influx of cash for them. I think we're going to see a lot more consolidation come out of this."

Maraviglia, the mother of Ara in Arroyo Grande, said she'll continue fighting for a future that gives families like hers access to more affordable health care.

"I think once you're actually part of the system you go, 'This is so messed up,'" she said. "It moves people into bankruptcy and financial distress, just because they want to live. They don't want their kids to get sick. We're trying to keep our kids alive." Δ

Assistant Editor Peter Johnson can be reached at [email protected].

This article has been edited for accuracy.

Comments (3)

Showing 1-3 of 3