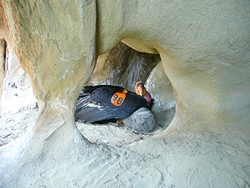

- PHOTO COURTESY OF U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE

- UP ON BITTER CREEK: The condors are assisted by refuge biologists, who often belay into mountainside nests to check on chicks and eggs.

Imagine, as you stand on a grassy plateau overlooking the thirsty San Joaquin Valley foothills, three school buses soaring through the air about 40 to 50 feet above your head.

Now replace the bright yellow paint and several tons of metal with the cream-and-charcoal feathers and naked pink flesh of a California condor.

Typically weighing in at 20 pounds, and with a wingspan of approximately 9 1/2 to 10 feet, the California condor is the largest land bird in North America.

The species would have died out completely in the late 1980s, however—if not for the efforts of some dedicated biologists.

After decades of being hunted, as well as exposed to lead and the insecticide DDT, the California condor population dwindled to less than 26 birds. Faced with the possibility of witnessing a species extinction, biologists and zoologists scrambled to launch captive breeding programs at the San Diego Wild Animal Park (now the San Diego Zoo Safari Park) and the Los Angeles Zoo, and started transporting the remaining birds, and their eggs, down south.

Biologists captured the last wild condor, AC9, on Easter morning in 1987.

“For the first time in tens of thousands of years, there were no California condors soaring in the sunny skies of Southern California,” wrote Jan Hamber, a condor biologist at the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History, and Bronwyn Davey, in an article on the Santa Barbara Zoo-associated website, sbcondors.com.

“At the time, it seemed that it was the end of the road for the wild population,” the article said. “All those involved in the program felt a pervasive sadness. Would these majestic birds of the sky ever soar again?”

From the brink and back

- 'CONDOR ZONE' 4-1-1: For more information about the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Condor Recovery Program, visit fws.gov/refuge/hopper_mountain/. More information about non-lead ammunition can be found at dfg.ca.gov/wildlife/hunting/condor/.

The simple answer to that question is, “yes.”

But the story of how California condors were able to once again take flight isn’t as simple.

“It’s pretty amazing—there are birds now that are breeding that I worked with about 15 to 17 years ago,” said Steve Kirkland, a field coordinator for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s California Condor Recovery Program, which monitors and cares for protected condor populations in Tulare, Santa Barbara, Ventura, and Kern counties.

“I think it’s amazing that any of them have been able to survive, honestly,” Kirkland said.

The success of the zoos’ captive breeding programs led biologists to start reintroducing condors to the wild as early as 1992. When last checked, the population had soared to 436 birds, with 123 flying free in Central and Southern California.

“We’re continuing to see an increase in more natural reproduction,” Kirkland said. “Hopefully, what we’re seeing in the field will offset mortalities due to lead and other factors.”

According to research done by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, U.C. Santa Cruz, the University of Colorado at Boulder, and others, the vast majority of California condor deaths are caused by lead poisoning—and, at least 75 percent of the time, the birds were exposed to lead by ingesting bullet fragments lodged in the carcasses of dead animals.

- PHOTO BY HENRY BRUINGTON

- NATURAL BEAUTY: Bordered by the Transverse mountain ranges, Bitter Creek Canyon is part of the roughly 23,000-acre Bitter Creek National Wildlife Refuge.

Joseph Brandt—a biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and supervisor of the condor recovery program—explained the effects of lead poisoning while giving a tour of the Bitter Creek National Wildlife Refuge. Located off of California State Route 166, just past the Kern County line, the refuge is home to at least 70 condors.

“[Lead poisoning] is a pretty horrible way to die,” Brandt said.

“Condors are opportunistic scavengers; they don’t chew their food, they just swallow it in mouthfuls. Being on the ground is dangerous for them, so it’s all about eating as much as they can, taking off, and finding a place to roost and digest,” he explained.

Because of their eating habits, the birds can’t tell when they’ve swallowed bullet fragments, which can stay inside their systems for long periods of time.

“The neurotoxin causes paralysis of their digestive system, so while they still might be able to eat, they’re actually starving to death,” Brandt said.

Condors store food in their crops—pink fleshy pouches on their chests—but when their digestive systems are paralyzed, the crop “fills up and festers with infection,” he said.

Veterinarians at the Los Angeles Zoo saved one condor by flushing its crop and then repeatedly pushing small amounts of food into its digestive system by firmly running their hands up down the bird’s neck.

- PHOTO COURTESY OF U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE

- GET THE LEAD OUT: Brandt and his fellow biologists perform chelation therapy—leaching lead and other metals out of the blood—on a sick condor. Approximately 30 percent of the refuges more than 100 birds require chelation at some point in their lives.

The bird lived—after losing more than half of its body weight.

To help the condors survive, biologists have devised a hands-on program that involves tagging birds with radio telemetry sensors, monitoring newly laid eggs, removing micro-trash from nests, and leaching lead and other metals from the birds’ systems through a medical procedure called chelation.

According to data from the condor recovery program, approximately 30 percent of the birds have to be treated for lead poisoning in their lifetime.

The biologists who work with the birds are incredibly dedicated to their wild charges. Brandt, for example, frequently belays down craggy rock formations to enter the nests of mating pairs to check on eggs or chicks. He and the other refuge staffers also trap each of the condors at least twice a year to check their blood for lead and, if necessary, perform chelation.

“It’s like having 70 children,” Brandt said as he drove us toward one of the condor traps on the plateau above Bitter Creek Canyon.

As we stood by the trap, a pair of condors took off from the feeding station across the canyon from us. Even at a distance, the birds—with their long dark wings fully extended—were impressive, as was the effortless way they floated above the countryside.

Watching the birds reminded me of something field coordinator Kirkland told me on the phone several days before our visit: “That’s what they’re designed for; to cruise and soar on the wind, to travel long distances and find that carrion.”

Get the lead out

![WHO’S THERE?: “[Condors are] hilarious, the way they’re always interacting with each other,” condor recovery program supervisor Joseph Brandt said. “People say they’re kind of ghoulish looking, but their personality wines you over.” - PHOTO COURTESY OF U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE](https://media2.newtimesslo.com/ntslo/imager/u/blog/2924524/cover.condors.face.3-27.jpg)

- PHOTO COURTESY OF U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE

- WHO’S THERE?: “[Condors are] hilarious, the way they’re always interacting with each other,” condor recovery program supervisor Joseph Brandt said. “People say they’re kind of ghoulish looking, but their personality wines you over.”

The goal of the condor recovery program is to get the birds to the point that they can be self-sustaining in the wild.

As Kirkland put it, “We want to get out of the business of actively managing [condors].”

The best way to do that, according biologists like Kirkland and Brandt, is to get rid of lead ammunition.

In 2008, the California Legislature passed the Ridley-Tree Condor Preservation Act, requiring hunters to use non-lead ammunition while hunting in the “Condor Zone.” This zone encompasses much of the condor’s historical breeding range; on a map of California, it forms a horseshoe shape from San Jose, down to Los Angeles, and back up to Madera.

The controversial bill received ample criticism from hunting enthusiasts of all levels and, to a lesser extent, ranchers. Their biggest complaints included the cost of non-lead ammo—copper bullets are the most common—and what some call the inconclusive nature of data linking lead ammo to condor deaths.

Brandt and many of his colleagues, however, feel that the law has some major loopholes. First, the sheer size of the zone makes the law difficult to enforce because there are only so many game wardens to go around. Second, the law doesn’t account for “nuisance” animals, such as coyotes and pigs, which feed on crops and livestock, or the livestock themselves.

In fall of 2013, Gov. Jerry Brown signed into law a bill that bans the use of lead hunting ammunition in all of California. The non-lead ammo is to be phased in by 2019. The language of this law applies to “all wildlife, including game mammals,” but, like its predecessor, doesn’t include livestock.

Brandt explained that “putting down” sick or injured livestock falls under agricultural code, whereas hunting and other forms of depredation fall under fish and wildlife code.

After making close to a dozen calls to local hunting outfitters to get their perspective on the non-lead ammo laws, only one called back. Alfred Luis owns Central Coast Outfitters and guides hunting expeditions in Santa Barbara and San Luis Obispo counties.

Luis said he switched to copper bullets before the Ridley-Tree Act passed in 2008 because he was “very pleased with their accuracy and performance.”

Some hunters have argued that copper bullets don’t work as well as lead and consider the lead ones more humane because they bag a “cleaner kill.”

- PHOTO COURTESY OF U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE

- FAMILIAL BOND: The California condor is known for its attentive parenting. Chicks usually stay with her parents for about two years before joining up with other juveniles.

However, Luis said he and the other hunters he knows haven’t had any issues with copper bullets.

“In my experience, if the rifle is used with the right caliber and shot properly, there aren’t going to be any problems,” he said. “[Copper bullets] retain all their weight, they penetrate well, and they open up.”

When asked what he thinks about the Condor Zone, Luis said he hasn’t seen the data to prove that lead poisoning is what’s harming the condors.

“I think Mother Nature selected them for extinction long before we got involved,” he said. “I don’t see them surviving without us helping them and feeding them.”

He also feels that the law is difficult to enforce because of the sheer number of people who hunt and the fact that most other states don’t ban the use of lead ammunition.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, along with several partners, is currently reaching out to California hunters and ranchers to educate them about the non-lead ammo laws and the effects of lead on not just condors, but all scavenging wildlife.

Advocates with the Ventana Wildlife Society in Monterey County have gone as far as to give hunters free copper ammo that has been paid for with grant money and donations.

The biologists at the Bitter Creek wildlife refuge and its parent refuge, Hopper Mountain in the Ventura wilderness, are in the process of acquiring ammo for distribution. Hunters and ranchers receive ammo based on where the birds feed or by raffle.

“Laws don’t always make things easier. Usually it’s harder to talk to someone if you’re saying, ‘you can’t do this,’ and wagging your finger,” Brandt said, adding that free ammo helps get the conversation started.

“It can be frustrating because [condor biologists] tend to get labeled as anti-hunting. If anything, we want to see an increased number of hunters out there because it’s beneficial to the birds. We just want them using different ammo.”

This is news to outfitter Luis, who said, “If you know someone giving away free ammo, let me know.”

Amy Asman is Managing Editor of New Times’ sister paper, The Sun. Contact her at [email protected].

Comments