The bustle of downtown San Luis Obispo might trigger thoughts of a successful economy, but the state categorizes the city as a disadvantaged community (DAC), much to the surprise of SLO Utilities Director Carrie Mattingly. She, along with the rest of the department, had no idea the city fell under that label until the county told them.

- PHOTO BY JASON MELLOM

- LABELED: On the surface, the city of SLO doesn’t appear to be in need, but according to the U.S. Census Bureau the median household income number defines the city as disadvantaged.

The water resources engineer of the SLO County Public Works Department, Mladen Bandov, approached the city’s utilities department last year after the county applied for a grant to help with water projects in the region.

Bandov is in charge of notifying qualifying communities of the new Proposition 1 grant funding being distributed locally to disadvantaged areas. He’s working with the entire Central Coast—which includes Santa Cruz, Monterey, San Luis Obispo, and Santa Barbara counties and parts of San Mateo, Santa Clara, San Benito, and Ventura counties—to allocate the money to deserving projects in communities that have low household incomes. The city of SLO was one of five communities in SLO County to be labeled as disadvantaged, but two of those communities question whether it’s valid to categorize SLO as disadvantaged and whether the city deserves access to the grant funding.

San Simeon and Oceano community services districts objected to SLO’s grant allocation. They questioned how just one factor, the median housing income, could be used to categorize a community. Both districts are seeking funding to improve failing water infrastructure such as leaky pipes, and SLO is looking to upgrade its water resource facility.

A disadvantaged community

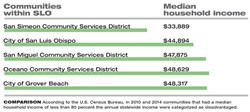

The main qualifier to get the DAC label is if a community has a median household income of less than 80 percent of the state’s median household income ($61,320). According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the San Simeon Community Services District (CSD) had the lowest median household income in the county with $33,889, the city of SLO was next with $44,894, then the San Miguel CSD with $47,875. Oceano CSD’s is $48,629, and the city of Grover Beach’s is $48,317.

“San Simeon was the lowest, and SLO came right after that as far as being the most disadvantaged,” Mattingly said. “Which was really interesting to us, because we didn’t really think of ourselves that way.”

Mattingly said she questioned the label until she looked at the 2010 to 2014 U.S. Census data and saw that the city’s median household income was the second lowest in the county.

Mattingly said she didn’t realize how many people were barely making ends meet living in the city and choosing to do so because they want to be in this area.

“They’re struggling so much that I think a huge part of their pay goes toward rent, so I think I can only trust the census data,” she said.

According to the city’s general plan housing element, in 2010 households within city limits earned an average of about $42,000. The document states that this number reflects a “high percentage of student households” but doesn’t detail any further specifics. New Times reached out to the city for more information on the breakdown of student households versus full-time residents and heard back from director of community development Michal Codron.

“We’ve been looking high and low to track down a source for that information. What we found is that statement appears in our 2004, 2010, and 2015 housing elements. No data source is attributed to the starement,” he said through an email.

Cuesta College doesn’t offer housing for its students; so many live off campus. Cal Poly students who don’t live in dorms or on-campus apartments live off campus in single- or multi-family rental units. The housing element also said that while household incomes were lower than other areas of the Central Coast, the median city housing costs were higher.

Although the general plan points to students as contributing to SLO’s low median household income, Mattingly said that they couldn’t define exactly why the city’s household income is so low.

“I think at the core of being a disadvantaged community, especially being identified as one of the lowest, I would not jump to the conclusion that it’s the students,” she said.

Being labeled a disadvantaged community gives SLO and other local communities a chance to kick-start their water improvement projects through a noncompetitive grants portion of Proposition 1, also known as the water bond. The measure, approved in 2014, authorized $7.12 billion in bonds for water supply infrastructure projects around the state; $520 million is set aside for disadvantaged communities within the various funding areas of the state. The Central Coast funding area received a minimum allocation of $43 million through the water bond.

This grant is the first of its kind for California, and it’s unique in the sense that the amount of money that specific disadvantaged communities receive is decided at the local level. Each funding region chooses how to split the money and collaborates to send each of the proposed water projects to a department within the California Department of Water Resources for approval. The department, called Integrated Regional Water Management (IRWM), aids regions in implementing projects to increase self-reliance, reduce conflict, and manage water to achieve social, environmental, and economic objectives specific to each region.

Deciding how the Proposition 1 money is distributed among the five local disadvantaged communities—SLO, San Simeon, San Miguel, Oceano, and Grover Beach—is up to SLO County with the assistance of the regional water management group and a subcommittee.

“How they internally part things out amongst themselves, the state doesn’t really want to get involved in because it’s really not a part of what our ‘request for proposal’ put together,” IRWM Project Manager Craig Cross said.

- PHOTO BY JAYSON MELLOM

- DISCLAIMER: The city of SLO had no knowledge of being classified as a disadvantaged community but ran with it to receive grant money to upgrade its water resource facility.

He said the role that his department plays in the water bond funding process is to make sure the proposals are consistent with the proposition requirements and to continually assure that the community follows through with the initial project proposals.

Cross said that a DAC must create a proposal that identifies what the project is and how it’s going to affect the community it will serve—whether it’s outreach within a community, designing the blueprints for a well, or updating a water master plan.

“You’re going to have to include it in your proposal, how building that project better involves a disadvantaged community in your region’s IRWM process,” Cross said.

The city of SLO plans to involve its disadvantaged community in its water projects by eventually having a learning center that will educate residents on where their water comes from and how it’s used.

The city of SLO is getting $78,125 of Proposition 1 funding, which will go toward community outreach and upgrading its Water Resource Recovery Facility. The facility treats sewage water from the city, Cal Poly, and the SLO County airport. It processes about 4.5 million gallons of wastewater per year. Mattingly said that the department is mandated to upgrade the plant to meet the new requirements for its national pollutant discharge elimination system permit, which is issued by the Central Coast Regional Water Quality Control Board every five years.

Mattingly said there are bigger plans in store for the facility, such as an education center for anyone who would like to learn about the city’s water processes.

“We want people to be able to go down there and learn about the complete journey from the reservoirs, all the way down through the city and all the other uses that we use it for,” she said.

Oceano

While the city of SLO is using the funds to meet permit requirements and community outreach, Oceano wants to use the grant money to fix its underground water pipelines. The district is hoping to get an allocation of $158,218.

Oceano has a population of about 7,000, but providing enough water to its residents isn’t the issue, said Oceano Community Services District General Manager Paavo Ogren. It’s the leaky pipes that convey that water. Oceano depends on three water sources: state water, Lopez Lake, and groundwater. Ogren said his district has one of the most reliable water sources in the county. But what comes with a reliable source of water is costly, he said.

“We spend more than 50 percent of our water budget on buying water from the county, and that cost has led to some deferral from infrastructure replacement,” he said.

The district is currently in the beginnings of establishing a leak detection program with the help of grant funds from Proposition 84. Proposition 1 is a continuation of the Safe Drinking Water, Water Quality and Supply, Flood Control, River and Coastal Protection Bond Act of 2006—also known as Proposition 84. The main goal of the proposition is to improve water quality and flood control. Through Proposition 84, the district will evaluate the system, where the leaks are and what pipelines need to be replaced.

“We’ve got some serious antiquated infrastructure in Oceano, pipelines that have been in the ground for far too long without being replaced,” Ogren said.

During the pipeline leak detection process Ogren said that he’ll also take a look at the 2009 master water plan and develop a capital improvement plan to replace the outdated pipelines, and that’s where the Proposition 1 grant money comes into play. The district has proposed project development activities in the amount of approximately $158,000 toward creating the designs and getting the project ready for construction.

“An eligible use of that is to start doing the design work, and that’s not going to pay for all the design that needs to be done, but it’ll definitely be a kick-start for our highest priority project,” Ogren said.

He said with this grant money it’s easier for communities to be able to apply for grants with just the starting blueprints when most grant proposals require the project to be “shovel ready.”

“In the big picture, this is a great opportunity for Oceano because Oceano is strong in terms of sources of water supply but those costs for the last couple of decades led to deferred infrastructure,” Ogren said.

He said he was surprised that the city of SLO was put into the DAC category because when a subcommittee of the regional water management group formed to present each community’s draft project proposals, the city of SLO wasn’t present.

“When we were working at the subcommittee level—I should say that it wasn’t characterized that we were purposefully excluding the city of SLO or saying they didn’t qualify, but it was a local subcommittee effort to look at it and say, ‘OK, now we have the basic guidelines,’” he said.

Moving forward with the median household income information, the county eventually notified SLO about its potential share of the grant money. Ogren said that although the data is there, it’s hard to tell what the particular cause of the DAC label is for SLO.

“It really wasn’t a, ‘Do they meet the criteria and the statistics,’ because those aren’t published by us. Those are published by the Department of Water Resources and others. The median household income is the data we all saw,” he said.

In a letter to the regional water management group, the Oceano CSD board of directors acknowledged that the median household income was a statistical calculation that identified the communities as disadvantaged, but argued that other measures should be considered as there wasn’t a statistic used that showed what resources are available to communities.

San Simeon

Along Highway 1, where the blue waters meet the green pastures of Hearst Castle, a quiet San Simeon CSD also sent a letter to the regional water management group voicing a rebuttal against SLO getting a piece of the Proposition 1 pie.

“By taking funds from the DAC allocations, the city of San Luis Obispo is taking money from the poor communities in this county, which really needs the grant funds to move projects forward and maintain vital services,” said Renee Osborne, San Simeon CSD administrator.

- GRAPHIC BY ALEX ZUNIGA

- COMPARISON: According to the U.S. Census Bureau, in 2010 and 2014 communities that had a median household income of less than 80 percent the annual statewide income were categorized as disadvantaged.

The main source of water for the district comes from the Pico Creek aquifer that sits right against the ocean. Charles Grace, San Simeon Community Services District general manager, said the community often had an issue with saltwater intrusion in their creek contaminating its drinking water. In May of last year, the district solved that problem by establishing the wellhead treatment plant, a facility that puts water through a reverse osmosis process to create potable water. When saltwater starts to intrude, the plant is turned on. So the facility doesn’t operate year round, but rather on a situational basis. Proposition 1 would fund the next hurdle the district is looking to overcome, which is to update the reservoir tank that stores water for things like fire emergencies. In its proposal the district is hoping to get an allocation of $158,218.

“It still is in compliance, but we know it’s not going to continue to be the sound structure that it is today,” Grace said.

The CSD needs to meet requirements established by the California Department of Forestry (CDF) fire marshal and the California Fire Code. Grace said the current reservoir is more then 50 years old, and while it’s still in compliance with the current fire flow requirements, the community’s population is growing and there is a need for a greater water storage capacity.

Grace said the grant money will help the district create a plan and get a project ready to replace the aging tanks and ensure an adequate storage capacity for the growing community.

“A disadvantaged community should have the ability to provide a viable water source to help individuals live a comfortable life,” Grace said.

When asked about the district’s comments about their prior questioning of SLO’s disadvantaged label, Grace declined to comment.

Moving forward

With the concerns over SLO getting a share of the disadvantaged communities funding, the regional water management group found a solution that pleased all parties. Oceano CSD General Manager Ogren said that in the end, the city of SLO didn’t get an allocation from the DAC funding pool.

Proposition 1 funding is split into four allocations: disadvantaged community involvement, planning grants, disadvantaged community projects, and implementation grants.

Instead of taking funds for the city of SLO from the disadvantaged community involvement portion, the regional management group is funding the city’s project from the implementation grant pool, which is a competitive grants pool that equals a little more than $6 million for the Central Coast.

Now the DAC funding pool is left untouched for the initial four communities in need. And taking money from the competitive pool wouldn’t have a huge impact on the other grant applicants, according to Ogren.

The disadvantaged communities grants are expected be awarded to the four remaining communities in 2018.

Staff Writer Karen Garcia can be reached at [email protected].

Comments