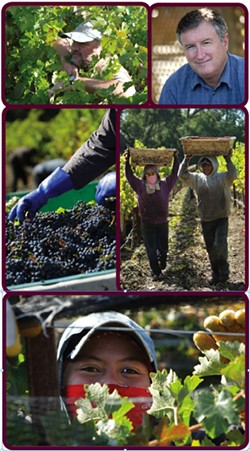

- PHOTOS BY STEVE E. MILLER

- TAKING CARE : Creating sustainable wine involves paying attention to natural and human resources. Winemaker Mitch Wyss of Halter Ranch (above left) and viticulturist Dana Merrill of Pomar Junction (above right) have produced some of SLO County’s first “certified sustainable” wines—with the help of hardworking vineyard workers with higher-than-normal wages and benefits.

It’s noon on the final day of this year’s wine-grape harvest, and Berta Mendoza and Maria Cerna eat their homemade tacos, sharing stories and laughing together as they sit in the shade in an unusual trailer parked at the edge of an Edna Valley vineyard. It beats crouching in the dirt in the hot sun at lunchtime, Mendoza agrees.

The curving canopy of the specially made rolling lunchroom isn’t the only way these farmworkers are covered. Under a new Central Coast certification program for sustainability, points are awarded to wine-grape growers whose hardworking vineyard crews are covered for medical insurance and are paid more than minimum wage. Some farmworkers are learning how to manage their 401K retirement accounts, matched dollar for dollar by their sustainability-minded employers.

“Sustainability in Practice”—or SIP—certification recently developed by the Central Coast Vineyard Team includes standards for the “three E’s” of sustainability, often referred to as three legs of a stool: ecology, economics, and equity. The SIP-certified seal, a voluntary program that was years in the making, now appears on 45,000 cases of wine from two dozen Central Coast wineries, produced from 10,000 acres of local vineyards.

Savvy wine consumers are starting to notice, as local tasting rooms begin to promote the distinctive SIP seal of approval, with the marketing slogan, “SIP the good life.”

“A lot of times people think sustainability is environmental. But sustainability also has a human resources component. Anybody in agriculture considers people their most valuable resource, and the SIP standards reward that—and require that,” explains Kris O’Connor, director of the Central Coast Vineyard Team, a national award-winning local network of farmers dedicated to sustainable agriculture research and education.

“I know lots of consumers care about the social responsibility side. They care about decent lifestyles, access to education, access to advancement,” she adds. And wine drinkers can be sure the certification isn’t just window-dressing: it’s been approved by experts from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, University of California, and the Natural Resources Defense Council, and all documentation supplied by growers is independently verified.

Industry insiders agree that social equity in agriculture is a hot-button issue today, as opinions on immigration issues in the United States have become increasingly polarized.

The wine industry, San Luis Obispo County’s biggest agricultural moneymaker, is deeply rooted in—and dependent upon—Hispanic labor. Under the shiny purple skins of recently harvested clusters of SIP-certified grapes lies the toil and sweat of brown-skinned workers. Most are Central Coast residents rather than migrants these days, according to farm-labor contractors.

Fair employment practices that eliminate discrimination are at the heart of sustainability’s social equity leg, along with a safe and fair work environment. Achieving the SIP standards also requires agricultural businesses to be “progressive in their thought process,” according to the introduction to the lengthy list of certification rules.

Dana Merrill hires a few hundred Hispanic workers every year. Merrill, the president of Mesa Vineyard Management, Inc., and owner of Pomar Junction Vineyard and Winery in Templeton, says treating vineyard workers well is good for business and good for people. “Oppressed people just don’t do very good work,” Merrill says matter-of-factly.

His labor-contracting company employs 100 full-time and around 200 part-time people—60 percent of their workers are women—who take care of thousands of acres of vineyards, stretching from Los Alamos to San Ardo. Half of the foremen are women, and many of the seasonal workers return to the company year after year. During nearly 30 years in business, he says, it’s been “rare” for any Anglo to apply for a job in the vineyards.

Merrill and the company’s vineyard manager, Gregg Hibbits—both from multi-generational local farming families—helped write the social equity portion of sustainability certification, which goes well beyond state and federal labor requirements. It was peer-reviewed by 60 people, Hibbits says, and includes provisions for employee performance evaluations, a grievance and complaint process, a displinary program with stepped procedures and opportunities for employee input.

“It’s a heartfelt, experiential system, based on what we think it important, not concocted by a bunch of liability attorneys. It was a genuine effort by growers to put a meaningful protocol together,” Merrill notes.

The company pays 100 percent of health insurance costs for all its employees, including fieldworkers, during the vineyard season, plus vacation and holiday pay, and extra incentives to reward a safe work record. Education and training are emphasized, and wages they pay are higher than the state minimum.

“We offer a 401K to everybody; we pay dollar for dollar on the first 5 percent. The seasonal people have really caught on. They’re putting money in it,” says Merrill.

“The women are especially interested,” says Esther Kosty, Mesa’s bilingual human resources manager, “so we’re educating them on setting themselves up for the long term. We let them know they can borrow from it to send a kid to college or buy a house.”

Merrill has returned from a daylong training session the previous day in Guadalupe, required for his labor-contractor’s license. Around the conference table in Mesa’s Templeton office, he discusses the “Top 10” concerns of farmworkers.

Fringe benefits, a good rate of pay, safety regulations, opportunities for advancement, a team approach to management, a grievance process, and tasks for older workers are on the list, Merrill tells Hibbits and Kosty. The No. 1 concern of farmworkers: respectful and fair treatment.

Kosty, a Hispanic herself, says respect is especially important in the culture.

“Social equity certification is pushing you toward these Top 10,” Merrill tells a visitor. “The whole idea of the social equity side of sustainability, it does add to your cost, but I think people work harder, they’re healthier, they’re happier.

“We do basically have a good story to tell. They make more in an hour than they’d make in a day in Mexico, and they’re doing jobs nobody wants to do.”

Both Mesa Vineyard Management and another large farm-labor contractor, Pacific Vineyard Company of Edna Valley, treat their workers to twice-yearly appreciation barbecues in recognition of a job well done, with prizes for vineyard crews with an accident-free season.

At Pacific Vineyard Company’s Oct. 24 harvest barbecue in the shade of the sycamore trees at Biddle Park on the day after picking is finished, farmworkers Mendoza and Cerna are hard to spot without the head-to-toe clothing covering their skin in the company’s shade trailer a day earlier. Like their workmates, they’re attending the barbecue with their families, and everyone’s dressed for a fiesta.

- PRACTICING SUSTAINABILITY: The new “Sustainability in Practice” standards differ from organic, biodynamic, and Fair Trade certification by looking at the whole farm system: human resources, habitat conservation, energy efficiency, pest management, water conservation, and economic stability. Although 24 Central Coast vineyards are growing certified sustainable grapes, so far there are only five wineries with certified 2008 vintages: Baileyana-Tangent, D’Anbino, Halter Ranch, Pomar Junction, and Robert Hall. Find out more at sipthegoodlife.org.

People who’ve worked with the company for five years, or multiples of five, are due to receive a free jacket this year. Everyone gets a knitted hat to help keep warm during vineyard pruning this coming winter. All the children line up for a toy, then run to their parents with noticeable excitement. There’s a picnic table loaded with dozens of raffle prizes, things like a Leatherman tool, an electric shiatsu pillow massager, an ice chest, a coffeemaker, flashlights. Grand prizes are a karaoke machine and a flat-screen TV—just what Mendoza and Cerna joked is missing from the shade trailer.

The foremen and supervisors are barbecuing the carne asada, and soon everyone’s plate is loaded up with hefty piles of meat, spicy rice, plump white beans, fresh green and red salsa, grilled jalapeno peppers, and a stack of corn tortillas.

“They’re hard, hard workers. They take a lot of pride in what they do,” says George Donati, general manager of Pacific Vineyard, who’s handing out plates at the front of the food line.

“Social equity is something we believe in,” explains office manager Mary Cooper. “We cover our employees for health insurance, and pay them more than minimum wage. Sometimes the public is misinformed; they don’t realize how much vineyards do take care of people.”

Smiling at the crewmembers, she says, “They’re the unsung heroes. Without them, no one would be enjoying any wine.”

Winemaker Christian Roguenant of Baileyana-Tangent pours a taste of his latest vintage into a plastic picnic cup for Jean-Pierre Wolff, owner and winemaker of Wolff Vineyards, as the barbecue smoke wafts through shafts of autumn sunlight under the trees. Their vines are cared for by Pacific Vineyard workers, and the wines they make carry the SIP seal.

For Wolff, one of the first winemakers to earn the sustainability certification, another part of the social equity section is also significant: “neighbor relations.” That’s especially important as more people move from urban areas to new housing developments in agricultural areas.

“An honest interchange of information is essential to lessen potential conflicts,” the introduction to the social equity section states. “When growers provide a progressive response to complaints, they encourage mutual respect and understanding where confusion and distrust have existed in the past.”

Donati has set up a system for his Edna Valley neighbors to call him if there’s a problem with lights shining into their homes or noise from bird-scaring devices, so he can take care of their complaints.

Sustainable practices are also applied to bird abatement in the vineyards, “a big issue” for neighbors in many parts of the Central Coast this year, according to Wolff. Certified sustainable vineyards have responded by using netting and reflective devices rather than loud cannons, and some have switched to a new generation of digital bird-scaring machines that emit the sound of birds in distress.

SIP-certified vineyards also rely on Integrated Pest Management, with targeted, softer pesticides, Wolff says. Vineyard workers are trained to recognize various insect pests, so treatment can be applied before an infestation gets out of hand—“unlike in the olden days, when you’d nuke a vineyard for a mealybug infestation, with a 10-day quarantine before re-entry.”

Pacific Vineyards viticulturist Erin Amaral agrees, adding, “The workers don’t leave the fields smelling like sulfur anymore. It’s good for worker safety too.”

The weekly English classes offered by the company are on hold now, with many of the vineyard workers already laid off until pruning time. After the barbecue, some will switch to working in local vegetable fields, while others will be heading out of town for family gatherings over the holidays.

Regular Thursday afternoon English classes are also on hold at Halter Ranch vineyard in Adelaide for a couple of months, while the teacher is on maternity leave. Halter Ranch winemaker Mitch Wyss, whose latest vintages bear the “Sustainability in Practice” SIP seal, strongly believes in helping his vineyard crews get ahead by learning English. Wyss also pays much more than minimum wage, especially for longtime employees.

“Agriculture is brutal work,” he says. “It’s freezing in winter, and blazing in summer. It’s six days a week, ten hours a day. Picking starts at first light, when the moon and stars are out. It’s farming with a capital F. It really is a tough, tough job.”

All the workers at Halter Ranch are welcome to the harvest from the employee vegetable garden and eggs from the chickens. More than 100 fruit trees are going in this winter, for workers to harvest for their own tables when they start bearing.

Housing is provided on the ranch for the foreman, and Wyss hopes to offer housing to more workers in the future.

“What you see today is really just a photograph of what’s going to be a 100-year movie,” he says.

Sustainability is “a moving target,” as O’Connor of the Central Coast Vineyard Team notes, adding, “We can always be doing more.”

As for Michael Blank, directing attorney of the San Luis Obispo office of California Rural Legal Assistance, he’s “delighted” that employers are taking care of workers in the vineyards, and says sustainability makes sense since we have to live in harmony with people and the planet.

“Really well cared for workers are productive workers.

This emphasis on social equity is a great start, and it would be wonderful if it spread to the entire wine industry, with guilt-free, socially just wine.

“Farmworkers are part of our community. They live with us. You judge the quality of a society by how it treats its least powerful members.”

Blank points out that the local wine industry has come a long way since a New Times article in October 1990 about poor treatment for farmworkers (“Bitter harvest: worker complaints of substandard living and working conditions have brought Arciero Winery under investigation,” by Kathy Johnston).

“I’m very happy to see the progress in some vineyards since the bad days of the “bitter harvest” article,” says Blank.

“I’d encourage wine connoisseurs to drink wine created with social equity so everyone can share in the richness of the harvest.”

Award-winning environmental journalist Kathy Johnston can be reached at [email protected].

Comments