When most young children are crawling on the floor, eating Cheerios, and learning to walk, the children of meth are navigating needles, hazardous chemicals, and drugs. In living rooms and bedrooms, children of meth users get a front-row seat for the frightening scene of a country struggling to deal with a drug problem, and they are often the silent victims.

Investigation reports written by the SLO County Narcotic Task Force, the agency that raids many meth houses, describe these homes in sterile detail. The following is written about a home in Arroyo Grande that housed a meth-addicted mother and her daughter:

- SLO County Narcotic Task Force

- TOOLS:

#“During the service of the search warrant, numerous hypodermic needles without protective caps were located on the floor, accessible to a two year old child along with numerous other child endangerment concerns. Several glass methamphetamine pipes, 2.5 grams of marijuana, and a handgun with ammunition was also located … Note: there were over fifty used syringes with needles in reach of [the child] along with knives, ammunition and a handgun.�

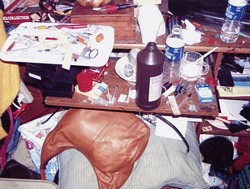

Mere words, though, can’t properly describe many of the homes of drug-endangered children. It’s the pictures showing piles of syringes, meth kept with children’s food, and meth stored with children’s toys that tell the stories. In the same report that’s mentioned above, members of the taskforce document conditions of the house in painstaking detail to secure culpability: “The living conditions of the residence were very poor, filthy and extremely hazardous ... There were nicotine stains on the walls, ceilings and window coverings throughout the residence. The nicotine stains were so bad that the stains were seeping through to the outside of the front door.�

About a year and half ago officials realized they were neglecting children during drug busts, so they “co-located� social worker Flora Sanchez with the drug task force team to help handle the children during raids. According to Sanchez, who preferred not to be photographed for this story due to the sensitive nature of her job, SLO County is fairly progressive for co-locating a social worker with the narcotics task force, a step that relatively few counties in California have taken.

Last year the task force worked more than 80 cases, many lasting months. This year alone 36 drug-endangered children have been removed from their parents in SLO County. Last year, Social Services removed 207 children, 89 of whom have yet to be reunited with their families. Because Social Services had only recently started tracking stats for drug-endangered children, it was not able to say how many of the 89 were removed from meth homes.

When she goes on a raid, Sanchez says, “I’m looking for accessibility and endangerment [to drugs].� Building a case for child endangerment means showing that drugs are or were accessible to children. Parents often hide drugs in their children’s possessions, thinking the police won’t look there. Sanchez says it’s a surprisingly common occurrence and it only bolsters the case against the parents.

But most importantly, Sanchez is examining the health of the child. “I’m looking for behavior that doesn’t appear to be normal that will tell me maybe the kids got into some dope or they’ve been exposed enough so that there’s a concern that they need to be checked immediately.�

Telltale signs of children experiencing the effects of drugs are hypertension, headaches, stomach sickness, coughing, malnourishment, rashes, and sores.

At the bust

After what can be months of surveillance, wiretaps, and investigation, the narcotics task force starts a bust with a loud knock. “Police! Search warrant! Demand entry!� they yell. The team sweeps through the residence, repeatedly yelling the same phrase: “Police search warrant!� Because police often serve search warrants early in the morning, users are sometimes passed out; so passed out that they don’t even wake up when a team of heavily armed officers storm into their bedrooms.

- SLO County Narcotic Task Force

- FRIDGE:

#Once the detectives manage to rouse the individuals, they inform them that they are not under arrest but they will be detained until the search is completed. The detectives scour the residence and “secure� it. Meanwhile Sanchez is loitering nearby, waiting for a call from detectives.

Sanchez, who has been working as a social worker for seven years, said that this is where a major logistical breakdown used to occur regarding the children. Previously, detectives would serve warrants and arrest drug users but lacked adequate training and resources to deal with the children in the homes.

“The kids were kind of an afterthought for law enforcement for many years,� she said.

For District Attorney Gerald Shea and Tyler Burtis, former commander of the SLO County Narcotic Task Force, this meant actually placing a social worker on the task force, a method Burtis says only a few other counties in California have implemented.

After detectives secure the residence, Sanchez goes in and immediately seeks out the children.

“I always approach cautiously, even though I know it’s supposedly all ready for me to come in,� she says. “But my concern immediately is with the children. How many children do we have there? How old are they? Are they siblings? Are Mom and Dad here? I know kids get afraid in these kinds of situations. So when I go in, my first focus is where are the kids and where are Mom and Dad.

“By the time I get there. Usually law enforcement will have the parents seated in the living room and they allow the kids there with them. So when I come in, my focus — and this is just my style — [is,] I’ll approach the parents.�

Sanchez says that speaking with the parents seems to relax the kids. Once detectives find the drugs and it’s clear the children must be removed, then Sanchez gets down to the nitty-gritty. Does the child have a primary care physician? When was the last time he/she ate? Any allergies? And, most importantly, is there a friend or family member that can take [temporary] custody of the child?

“We try to find [a relative or family friend], because it’s the best option. It’s easier for the children to be placed with the family because they already have a relationship with them,� says Sanchez. The alternative is placing the child in an unfamiliar foster home.

“I will ask the parents, ‘Where can I take the kids?’ I try and chitter-chat with the kids. Then I ask the parents to help me with the transition. Again, it’s trying to eliminate any more discomfort for the children. It’s important for the kids to see me interact with the parents.�

If Sanchez can’t find a relative or family friend, then they have to place the child in a foster home. But for SLO County officials, someone the child is already familiar with is always preferable, says Sanchez.

“All the research is showing that children definitely do better when they’re with people they know,� said Debbie Jeter, deputy director of the SLO County Department of Social Services. The cost of placing a child in a foster home or with a friend or relative is equal, said Jeter.

How the kids see it

- SLO County Narcotic Task Force

- BEDROOM:

#Drug-endangered children seem to have a better understanding of drugs then most adults. They are capable of describing drug deals and how meth is smoked, snorted, and slammed (injected) in incredible and almost painful detail. At a bust, detectives will often ask the children to draw meth pipes and will ask them about drugs.

During one raid in Atascadero, detectives questioned 9-year-old Joseph (not his real name). In an official task force report, they asked him if he knew what dope is.

“White stuff, looks like sand but smooth,� he said. “[Mom] gives it to people for money. My mom sells drugs but she doesn’t use or smoke it. That is how we get our groceries.�

Joseph then showed Sanchez and the detectives how his mother’s drug deals go down in a hand-to-hand exchange. He “placed his hands palm to palm and slid them in an opposite direction,� the report states.

Joseph said that mostly his mom’s drug deals happened outside grocery stores. His mother would then take the money and buy groceries as Joseph and his two siblings waited in the car.

Joseph’s 10-year-old sister elaborated in greater detail about meth.

“They are, like, put in a bag and it’s white and bumpy. It comes in a big ball and you have to crunch it up into little pieces. Put it on a scale, it says how much it is. Like 25 ounces or something.

“I was 9 years old when she started selling it because we had no money. Friends gave her stuff so she can sell it. She gets $250 for selling it.�

Detectives asked Joseph if he was curious about what dope tasted like.

“Yeah, I wonder how it tastes, but I never taste it,� he said. Had he ever found white stuff? “Yeah, a little bit. Usually on my mom’s bed. In a clear bag twisted up. We would clean her bed of it and put it on top of the bed for her to see it.�

Did he throw it away?

“No, because then she wouldn’t get money.�

Chipping away at the meth problem

According to a July report from the National Association of Counties, there has been an 87 percent increase in meth-related arrests in the last three years. Fifty-eight percent of the counties in the survey said meth was their largest drug problem.

“You know, what I see about meth is, there’s an awful lot of it,� said Sanchez, “and it seems to be everywhere and it certainly seems to be in a lot of our referrals.�

And SLO County is not alone. Although Sanchez said the problem of meth is one you have to just “chip away at,� she thinks there’s been progress regarding the children of meth.

“Drugs have been here forever and ever and ever, and in a lot of these homes there have always been children,� said Sanchez. “And we’ve come from a place where law enforcement was focused on the crime and the people who were manufacturing dope, or selling dope, or using dope.

“Nobody was stopping to think maybe Mom and Dad are smoking dope and little Johnny is right there on the couch sitting next to them watching TV. So the kids were being handed off to someone just to get them out of the way, to get them out of that environment. But nobody was checking to see if they were okay.�

Staff Writer John Peabody can be reached at [email protected].

Comments