After seven years of water restrictions over the Paso Robles Groundwater Basin, San Luis Obispo County is redrawing the basin's boundaries, which will subject hundreds of new property owners to a moratorium on irrigating and other rules.

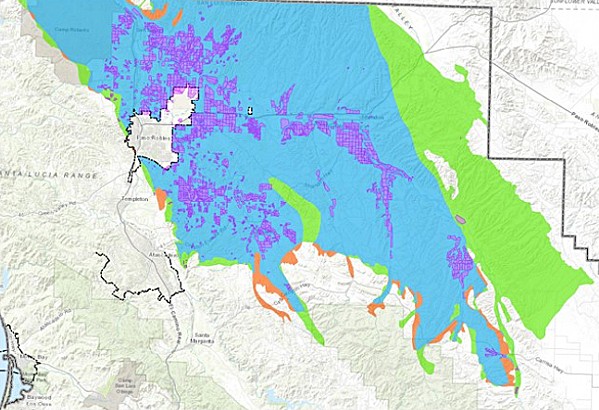

- Image Courtesy Of SLO County

- NEW BOUNDARIES SLO County is considering changes to the Paso Robles Groundwater Basin boundaries. The green areas would be added; the orange removed; the blue is unaffected; and the purple is irrigated crops.

The revised map is part of a package of changes to the county ordinance that regulates the 684-square-mile aquifer in North County. Passed in 2013 amid an ongoing drought, the ordinance was recently extended to 2022 to buy time for the Paso Groundwater Sustainability Plan—which is currently being reviewed by the state—to get implemented.

When the Board of Supervisors approved the extension in December 2019, it also authorized county staff to update the boundaries, review and redefine the "areas of severe decline," and develop a voluntary fallowing program.

But all of those changes received blowback from landowners and farmers at a June 11 county Planning Commission meeting. The new map—which is being updated to mirror the state's map—brings 524 new property owners into the boundaries of the basin and removes 244. It adds significant acreage to the basin's east, past Shandon, as well as some properties west of Paso Robles and Templeton and around Creston.

"Our small farm is on the edge of the proposed boundary," Kevin and Lisa Irot, of Templeton's Eyerit Family Olive Oil, wrote in a letter to the county. "Inclusion into the Paso Robles Groundwater Basin would restrict our ability to meet product demand and also severely devalue our property."

Because of the ordinance's ban on expanding irrigated agriculture over the basin, the Irots and other growers would not be able to increase the size of their farms under the new boundaries.

"Currently we utilize only half of our usable acreage," their letter read. "We would expect to increase our production by planting more trees to meet the increased demand for our products. ... We ask that you do not approve the proposed changes."

For years, SLO County managed the basin according to the boundaries it developed through its own contracted scientific studies. But the California Department of Water Resources (DWR) has a "very different" version of the basin, according to a county staff report, and DWR recently rejected a county request to modify that boundary to match the local version.

"Now [the two maps] are coming to a head," said Jay Brown, chairman of the Planning Commission. "I think we're going to have to have one map, one way or another."

Within the new basin map, the county is also proposing to change the areas that are considered "in severe decline," and subject to additional water restrictions. The new areas of severe decline add 300 property owners and remove 1,437. It mostly shifts the "red zone" from around and north of the city of Paso Robles to several miles east.

But landowners and planning commissioners both questioned whether there was sufficient well-monitoring data to justify the changes. County staff said the remapping was based on updated data from its well-monitoring network—the same type of data used to establish the red zone in the first place.

But officials acknowledged that that network is small. One of the first action items of the Groundwater Sustainability Plan is to expand the basin's well-monitoring network. Willy Cunha, a Shandon farmer and board member on the Shandon-San Juan Water District, voiced his opposition to the new red zone.

"The specific wells chosen to draw the contour lines are widespread, they're far apart one from the other, with large distances between them. The computer estimates and projects what might be happening in all the spaces in between," Cunha said in a June 11 public comment. "It's not a specific tool that would support regulations that cause uneven or unfair economic impacts. It would not hold up under legal challenge."

For San Miguel landowners Robin Chapman and Robert Galbraith, moving the red zone is welcomed. Chapman told New Times that she has well data showing that water levels have not declined under their land in more than 50 years—yet their property was included in the county's original red zone. While she's happy about the proposed remapping, she feels bad for those who are now part of it.

"I'm a conservationist. I do not regard water as endless. I think it makes sense to make plans for your resources. I'm just not sure how much of it is based on science and data," Chapman said.

Farmers also quibbled with a proposed fallowing program that is included in the ordinance revisions. Under the program, farmers could choose to fallow their fields and still maintain their irrigating rights in the future. But due to the ordinance sunsetting in 2022, growers said the fallowing period would be too short and its future too uncertain to be worth participating in.

In a unanimous vote on June 11, the Planning Commission recommended the county look at extending the fallowing program for a longer period of time and recommended against adjusting the red zone areas. The Board of Supervisors will review the ordinance changes at a meeting on Aug. 18. Δ

Assistant Editor Peter Johnson can be reached at [email protected].

Comments