It’s not very often that the lyrics to a Canned Heat song perfectly paraphrase the message of an exhibit hosted by the SLO County Historical Society. But the somewhat-socialist message, “together we’ll stand/ divided we’ll fall/ come on now people/ let’s get on the ball/ and work together” is surprisingly compatible with the 19th century goals and aims of the Farmers’ Alliance, an organization that swept through the county like wildfire in the early 1890s.

- PHOTO COURTESY OF THE SLO COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY

- 1918 : Bean farmers in Oso Flaco take a break from threshing.

The exhibit, which has been three years in the making, began as a display about the county from the 1870s until the Southern Pacific Railroad came churning through in 1894. But history professor Dick Miller insisted that the Historical Society was glossing over the real story, a cooperative organization with 31 suballiances and a powerful political hold in SLO County during the 1890s. So, the society shifted its focus, though railroads retained a significant role in the new story, as the exhibit’s villains.

“At that time in California, the railroads pretty much controlled all commerce,” said Pete Kelley, a Historical Society volunteer. At the same time, people were starting to do small farming because there were smallholdings. They had to sell their products in San Francisco and the railroad set the freight rates for the train, owned the mill that ground the wheat. Every part of farming was controlled by the railroad. To survive they had to do something so they decided to join the populist organization, the Farmers’ Alliance.”

In 1890, the county’s population was a mere 16,000, nearly double what it had been 10 years before, and the county would export 55 million pounds of wheat that year. While the county was primarily dedicated to producing wheat, Arroyo Grande was the bean capital and the North Coast, particularly the Cambria and San Simeon areas, had numerous dairies. Many of the county’s farmers had originally come to California during the Gold Rush; when the fever abated, they decided to remain in California and try their luck at farming. The Homestead Act, which Lincoln signed into law in 1862, also offered the promise of land to hardworking individuals. By living on and improving land, anyone was entitled to apply for the deed of title.

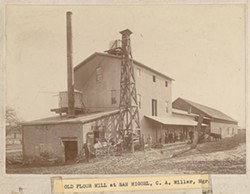

- PHOTO COURTESY OF THE SLO COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY

- CUTLINE : The San Miguel Flour Mill remains in operation today, but it played an important role in the power struggle between the railroad and the Farmer’s Alliance in the late nineteenth century.

On May 11, 1880 a group of railroad employees went to the slough to evict the settlers who had refused to pay. A shoot-out ensued, leaving seven men dead and sending five settlers to jail. These five men were later called the Mussel Slough Five, and regarded as heroes by the working man and woman. The Farmers’ Alliance exhibit includes a photo of the five jailbirds, courtesy of Hanford Carnegie Museum.

In San Luis Obispo County, anti-railroad sentiment helped drive more members into the welcoming fold of the Farmers’ Alliance.

“By the 1890s the economy was really going bust,” said Kelley. “It became a perfect storm of bad news for farmers—bad weather, monopolies controlling everything.”

The Alliance fought back with cooperatives. The Business Association organized an alliance-owned flourmill in San Miguel. Farmers bought Alliance stock certificates, and the cooperatives purchased and re-sold manufactured goods and building supplies at fairer prices. Farmers would exchange labor and products with one another.

The Alliance was politically active as well. It wasn’t necessarily synonymous with the People’s Party, but most of the local farmers were populists. In fact, in the latter years of the 19th century, the North County was considered quite radical.

“It’s commonly assumed in this county that the North County is the most conservative part of the county,” said Kelley. “They elect conservative representatives. So it’s kind of an irony that in the 1892 presidential election the Populist Party got more votes from the North County than any other precinct in the country.”

- PHOTO COURTESY OF THE SLO COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY

- LO! THE CAR OF JUGGERNAUT! : A train at the Paso Robles depot in the late 19th century.

When the Southern Pacific Railroad first rolled into San Luis Obispo on May 6, 1894, Steele went on the record saying, “We need a new deal. The political stables need to be cleaned out. While I do not fully endorse all the means advocated by the Populist Party, the leading measure, or political ideas, promulgated by that party are correct.”

Steele died in 1901, but the Farmers’ Alliance story doesn’t stop there. The classic struggle between the haves and the have-nots, and the efforts of agricultural workers to make a living for themselves while filling the nation’s refrigerators and supermarkets, will never grow old.

INFOBOX: Aging like wine

The San Luis Obispo County Historical Society is hosting its Farmers’ Alliance exhibit through the end of the year. The SLO County Historical Museum is located at 696 Monterey Street. The museum is open Wednesday through Sunday from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. On June 7, Michael Magliari, a professor of history at CSU Chico, will be a featured speaker at the museum. For more information call 543-0638.

Arts Editor Ashley Schwellenbach likes her vegetables deep fried or not at all. Send motherly scoldings and tales of clogged arteries to [email protected].

Comments