In the not-too-distant future, Allen Root will erect a new piece of public art in Mitchell Park paid for with your money. Many of you will admire this new creation for its colorful playfulness and clever design. Some of you will be left scratching your heads, wondering “Why did they pick that?�

Â

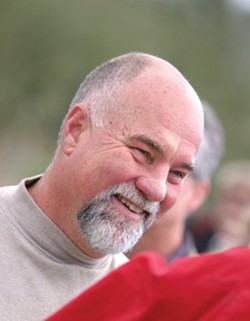

- PHOTOS BY CHRISTOPHER GARDNER

- MAN OF STEEL: Allen Root, one of SLO County’s best known public artists, have experienced his share of travails in dealing with the City of San Luis Obispo, but he keeps coming back for more.

Â

I, too, sometimes look around San Luis Obispo at our extensive public art collection and wonder, Is that the best we can do? Why is so much of our public art, well … pedestrian and boring! The answer is more complicated than you’d expect, but the short version is this: We get the art that we, as a community, deserve.

Â

Don’t be insulted. I’m not saying you’re pedestrian and boring, but how we fund public art, how we pick it, how we treat it, and how we value artists all conspire to severely limit our public art choices, which in turn result in public art that rarely challenges us. It becomes, at best, window dressing, and window dressing we frequently don’t seem to respect.

Let the damage begin!

Â

Kate Britton’s Garnet, that sensuously bulbous three-breasted bronze currently stationed in the parking lot of Nipomo and Higuera (you may remember that this “daringâ€? piece was ridden out of Old Town Arroyo Grande on a rail), is our most recent public art casualty. She’s been knocked from her moorings, no doubt by a collection of inebriated art critics raised on Beavis and Butthead and Jackass reruns. Your tax dollars will be used to fix her.Â

Â

- IMAGE COURTESY OF ALLEN ROOT

- PERPETUAL HOPE : This steel sculpture by Allen Root, the most recently awarded public art contract by the City of San Luis Obispo, will eventually be erected in Mitchell Park.

Â

Last year’s Trout About Town public art fundraising project for the homeless had several sculptures stolen, damaged, or otherwise vandalized. The city (i.e. you!) had to pay to have the sculptures better secured to their bases to avoid further damage.

Â

A few years ago the city attempted a rotating public art program in which sculptures were installed around downtown. It began with two pieces, Sandra Kay Johnson’s cat-and-fiddle sculpture Hey, Diddle Diddle, and Root’s Symbiosis. Johnson’s sculpture was stolen and Root’s was vandalized. Johnson cast another copy, which the city bought for $5,000 and added to its permanent public art collection. Root removed his sculpture. The program has been suspended.

Â

And that’s how the public—or at least the really lame segment of it—treats public art.

Â

Ergo, one of the design elements we, as a public art selection committee, were instructed to consider was the proposal’s ability to withstand graffiti and other forms of vandalism. One might be excused for thinking, What in the bloody hell is wrong with people in this community that they can’t keep their stinking hands off public art? If the public doesn’t value the public art program, why should the city continue it, and how are we going to attract talented artists to create work that will simply become a punching bag for Philistines and Neanderthals?

Going, going, gone…

Â

Our public art ordinance dictates that one percent of the total cost of new construction and capital improvement projects should be earmarked for public art. Whether for a public or private development project, the percentage remains the same … or does it?

Â

- PHOTOS BY CHRISTOPHER GARDNER

- WOMAN ON A MISSION: Betsy Kiser, SLO’s Public Art Coordinator (and new Parks & Rec Director), helps organize public art selection committees. Interested parties should call 781-7123 and indicate a willingness to serve.

Â

“Because of tough times, we decided to drop it to three-fourths,� explained Betsy Kiser, the Public Art Coordinator. “Then in 2005 we dropped it to one-half a percent. The City Council is strongly in support of the one percent ordinance, but we all had to tighten our belts.�

Â

Public art is getting squeezed by this belt-tightening. How do we attract artists to submit proposals when we offer them such meager recompense?

Â

Even Kiser admits that a half a percent often doesn’t buy much, which is why there’s a kitty into which collected funds can go to create bigger projects. The Mitchell Park project is a case in point for the too-few-funds dilemma. Originally $12,800 was set aside for the park. The Requests for Proposals (RFP) for that project first went out about three years ago, garnered several potential art works, went through a jury that selected a piece, which in turn was brought before the Architectural Review Board, which asked some hard questions about the possibility of erecting the work with the funds earmarked … and then the artist began to realize that she simply couldn’t produce the work for so little money. The project was a money-losing proposition. The artist withdrew her proposal.

Â

Kiser, who by all accounts is a huge public art advocate and a tireless worker toward developing our city’s program, found another $10,000 to add to the Mitchell Park project and put out another RFP and garnered a new set of proposals, which came before the committee I served on. Hence, we began the process again.

Is that all there is?

Â

A three-ring binder containing proposals for the Mitchell Park project was delivered to my New Times office. Excited as a kid on Christmas, I opened it up and began looking through the options. There were only six.

Â

- PHOTOS BY CHRISTOPHER GARDNER

- MAJOR PLAYERS : SLO Mayor Dave Romero and public arts advocate Ann Ream recently attended the dedication of Strong Play Ethic at the Damon-Garcia sports fields.

Â

My fellow jurists (Joy Becker, Barry Frantz, Bill Pyper, and Patti Sulllivan) met twice, a total of about five hours, in our efforts to determine the best proposal. The six design submissions were based on the RFP put out by the city, which called for something that reflected the playing children who frequented the nearby playground; its location in an older, well established SLO Town neighborhood; and that it act as a memorial to Elena [last name?], a young local child who had succumb to cancer(?).

Â

During our first session, we eliminated three of the six proposals: a standing abstract figure constructed of steel that appeared to be holding a ball; a large reclining abstract figure that suggested motherhood, reminiscent of a Henry Moore sculpture; and finally what appeared to be a large cylinder from which was cut the silhouettes of a series of skipping children (think of a giant soup can with a design cut in it). The first piece seemed too austere and coldly modern to reflect the playful nature of children, nor was there anything in particular tying it to the neighborhood or Elena. The second was too derivative of Moore’s work, not to mention unconnected to playing children and Elena. The final piece looked incredibly dangerous, like a cheese grater waiting to slice off the delicate finger of a small child. After briefly considering that attribute as a deterrent to vandalism, the design was summarily rejected.

Making the cut, in addition to Root’s winning piece (see the pictured artist’s rendering), was a symmetrical sculpture made of steel with symbols emblematic of the Mitchell Park area. It was rather easy for we jurists to figure out it was designed by Jim Jacobson, who already has more than half a dozen public artworks on display in the city, including the similarly designed kinetic sculptures along the creek walk as well as Flames of Knowledge, another mobile-like piece outside the Parks & Rec Department on Nipomo Street.

The final artist we chose to have return and make a formal presentation was Gary Garrett, who offered a bronzed sculpture of a small child’s hands formed to make a bird in flight. He had done a similar sculpture of a grown man’s hands, which he used as an example. But Garrett proposed to mount his sculpture on what appeared to be a plain concrete pylon thick enough to support a highway overpass. Bill Pyper said that the entire proposal looked as if it belonged in a cemetery, but we collectively decided to have Garrett come talk to us about it, mainly, I think, because his sculpture was the proposal closest to actual fine art … at least the bronze part of his proposal. Most of the proposals were corporate, commercial, or conceptual—creativity aimed at the lowest common denominator.

Garrett, a novice to the public art arena, was more than willing to accommodate the desires of the committee. He was completely open to our suggestions for redesigning the base, for instance. The real sculpture expert in our group, Barry Frantz, the retired Chairmen of Cuesta College’s well-respected Art Department, knew all the right questions to ask. Garrett planned to create the sculpture small and then have the foundry where it would be cast size it up to monumental scale, but Frantz knew the procedure didn’t always yield successful results. Small errors may charm a viewer when a sculpture is tiny, but blown up huge, the errors result in a sculpture that looks clumsy at best.

In retrospect, Frantz also worries that an artist with so unformed a concept, who is also so open to suggestions from the jury, will eventually deliver a watered down, homogenized version of his vision, resulting in art by committee, a surefire way to generate unadulterated pap. It was fairly clear, this was a two horse race: Allen Root versus Jim Jacobson.

Both artists were clearly up to the task. Each had completed multiple public art projects on time and on budget. Root had the biggest project under his belt, a $330,000 project for Palm Desert, making this $22,000 job look awfully piddly. I personally thought both artists’ proposals were worthy, but I questioned if the city really needed another Jacobson piece, especially one that looked so similar to his other designs. After a thorough discussion and vetting of the designs, the jury reached a consensus: We picked Root’s towering, colorful, whimsical, vandalism-proof, artistically safe, uncontroversial Perpetual Hope.

The Rodney Dangerfield of public art

Â

It’s a real tribute to Root that he continues to throw his hat into the public art ring. He knows, perhaps better than most artists, what it means to get no respect. He was the artist behind Community’s Bridge. Hmm, I see you saying to yourself, what’s that? What indeed! Root’s Community’s Bridge was the art-deco series of blue benches that used to be on Higuera Street in front of Copeland’s new Court Street Project.

Â

The benches were removed so they wouldn’t be damaged during construction of the new shopping mall, but after it was completed, the developers decided they didn’t want the benches back, even though Root designed the benches to remind citizens that right under Higuera Street, at the very spot they were installed, we had covered over San Luis Creek. The cream and green art deco mountain elements of the project are meant to remind us that on the other side of these tall building we’ve surrounded ourselves with, sit a chain of majestic mountains that run from the city to the sea.

Â

Root went through a jury, the architectural review, and the City Council to win the $33,730 project. It’s not entirely clear why the Copelands don’t want them back: maybe the design will interfere with traffic flow, though that sidewalk was purposely widened to accommodate the benches; or maybe too many transients sit on them disturbing commerce; or maybe the Copelands think they’re just plain ugly. It doesn’t matter, really, but ever since it became clear the benches wouldn’t be returned, the city has been trying to find a place to put them.

Â

At one point, it was suggested they go in front of the County Government Center. The benches’ deco elements seem like a natural complement to the Fremont Theater, and they’d still be close enough to San Luis Creek for that design element to make sense. While not his first choice—he wanted them back on Higuera—Root approved the location. It was a City sculpture going on County land, so City Administrator Ken Hampian approached his County counterpart David Edge, and the process to approve the installation commenced. Then Superior Court Judge Michael Duffy wrote a letter to Edge explaining how the whimsical benches didn’t reflect the serious nature of the work that went on in the County Government Center. No, really. Stop laughing; it’s true.

Â

Let’s hope that the public art proposals for the new County Government Center across the street meet the approval of everyone who works within that building. There’s $105,000 in art on the line, and it better be darn serious! Something bureaucratic! Maybe the entire structure could be wrapped, Cristo-style, in red tape!

Â

The City continued with its frantic search for a location for Root’s benches. After several possible locations were discussed and discarded, Root—who at least had been consulted throughout the process—and the city agreed to move the benches to Emerson Park (near the corner of Nipomo and Pacific Streets), even though their design has no real connection to that area. Root approved of the move for a couple of reasons: He figured they’d get used there; and the Copelands promised to build a bocce ball court at Emerson. “It was good for the community,� said Root magnanimously. The Copelands also promised the city they’d spend $15,000 on public art for the Court Street Project.

Â

But again, one can’t be faulted for wondering, if this is how we treat one of our best known public artists, if this is how we demonstrate how we value his talents and efforts, how can we expect to get better proposals, more proposals, and the kind of public art that we can really be proud of?

Something’s better than nothing

Â

Okay, I see steam coming out of a lot of ears. You think I’m

- PHOTOS BY CHRISTOPHER GARDNER

- TEAM EFFORT : Stephen Plowman, Carol Paulsen, and Stephen Van Stone joined forces to create Strong Play Ethic, a recently dedicated public art piece at the Damon-Garcia sports fields.

Â

And a lot of what we have, though unequivocally pedestrian, is still a pleasing addition to our urban environment. Strong Play Ethic, a piece by Stephen Plowman, Carol Paulsen, and Stephen Van Stone that was dedicated last week at the Damon-Garcia sports fields, is a real charmer and seems apt indeed.

Â

During last week’s dedication, the SLO County Arts Council’s Ann Ream, who is perhaps the biggest public art advocate in the County mentioned that the Food Channel’s Rachael Ray had decided to shoot an episode in SLO Town in part because of our wonderful public art program. Congratulations to us. We’re the greatest. But that certainly doesn’t mean we can’t do better. Public art is just that, public … yours … mine … ours. Let’s treat it as if it matters.

Glen Starkey will spend the rest of the week under a wrapping created by Cristo. Tell him he looks better covered up at [email protected].

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1