- PHOTO COURTESY OF MV GALLERIES

- OPULENT TEMPLE:

Somewhere in the expanse of inhospitable Nevada desert—between the cracked dirt and the unrelenting sun—a metropolis of artists, idealists, and anarchists blooms for one week out of the year, like a rare desert flower. It’s a city where art is central, radical self-expression is encouraged—especially if it involves pyrotechnics—money serves little purpose, and participation is mandatory. Its namesake is a purposefully ambiguous effigy, created for destruction at the close of the week: Burning Man.

San Francisco Bay Guardian editor Steven T. Jones first attended the freak festival in 2004. The year, which marked the beginning of a renaissance for Burning Man, was a devastating one for progressive political journalists like Jones, who had fought hard to remove Bush from office. Over the next few years, the connections between the psychedelic art fest and American political culture became increasingly clear to Jones, who made his observations the subject of many Guardian cover stories. And between the hordes of “burners” who put their skills toward disaster relief in the wake of Hurricane Katrina in 2005, the complex inner politics of the $10 million business that Burning Man became, and the 2008 art theme “American Dream,” (timed to coincide with the Democratic National Convention), Jones had more than enough material. His experiences shape the book The Tribes of Burning Man: How an Experimental City in the Desert is Shaping the New American Counterculture.

For the uninitiated, Burning Man began a quarter of a century ago as an obscure summer solstice beach party in San Francisco. After the police cracked down, the party set up camp in Black Rock Desert in rural Nevada, in an ancient lakebed that became known as The Playa. From its early, anarchic, rules-are-there-ain’t-no-rules beginnings, the event grew to the intricately structured, 50,000-strong civilization known as Black Rock City.

“This culture was really hungry to have its story told,” Jones told New Times, for which he wrote in the ’90s. “I think it’s such a rich and interesting story. I feel honored to be in the position to put the stories out there of so many amazing people who are doing really creative, innovative things, and in turn, building community and having an impact on their cities.”

- BURNIN’ UP: Buy The Tribes of Burning Man on Amazon, or visit steventjones.com for a signed copy. There’s a Tribes party in the works for San Luis Obispo, so stay tuned.

With journalistic instincts honed over 20 years of news reporting, Jones recognized the story potential inherent to Burning Man’s renaissance, rebellions, scandals, and luminaries—and their many effects on the city he called home. And he could ask for no better characters than the ones that colored his Guardian pieces, and eventually a comprehensive book. There was “Chicken” John Renaldi, instigator of a late-2004 art rebellion. The Flaming Lotus Girls, the tribe into which Jones immersed himself, taught him to make art from metal and fire as they constructed their giant artwork Angel of the Apocalypse. And Paul Addis, a crazed arsonist arrested for his highly controversial early torching of the Man in 2007, proved journalistic gold.

“Arson is arson, even in Black Rock City,” Jones writes in Tribes. “And if [Burning Man founder] Larry and the other leaders of Black Rock City LLC appreciated the art and irony of an old-school burner with a painted face and manic intentions rappelling off a prematurely burning 40-ft. wooden man at 4 a.m. like some kind of demented superhero, they didn’t show it.”

Burning Man 2005, Jones’ second burn, was viewed by founder Larry Harvey and many others as Burning Man’s best to date. The art was top-notch, the weather perfect, and the spirit of generosity and participation flourishing, in keeping with Black Rock City’s “gift economy” and rules against spectators. For many, 2005 was the year the event moved from frontier town to city.

Then, on the second day of Burning Man, Hurricane Katrina hit the Gulf Coast. When Burning Man decamped that year, a group of “burners,” many from the Bay Area, made their way down to the Gulf Coast in a nine-month relief project called Burners without Borders.

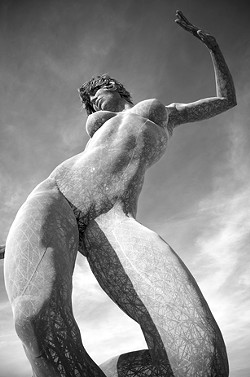

- ARTWORK BY MARCO COCHRANE, PHOTO BY LUKE SZCZEPANSKI

- BLISS DANCE:

“The very skills, tools, and motivation needed to stage Burning Man every year were exactly what the Gulf Coast needed,” Jones wrote, paraphrasing Harvey. The author flew to Louisiana to chronicle the group’s efforts for The Guardian, soon putting his pen and pad aside to lend a hand where he could. The resulting cover story was one of many to draw attention to the effect Burning Man, spawned and headquartered in the Bay Area, was having on the country and the world.

“The narrative of this book really wrote itself,” Jones told New Times, his voice hoarse from delivering late-night Tribes readings to badly behaved Bay Area audiences. “The sort of main spine of events and how they unfolded in unpredictable ways … I got lucky that it turned out like I hoped it would.”

Perhaps one of Jones’ oddest and most epic journalistic undertakings occurred in 2008, when he road-tripped from San Francisco to Black Rock City, then to the Democratic National Convention in Denver, and then back to Black Rock City before the week was up, churning out photos and stories all the way. The resulting piece explored the connections between the DNC and Burning Man’s “American Dream” theme, the political culture contrasted with the counterculture.

It takes a confident patience to paint such an intricate portrait as Jones has—one not meant to be ingested over a mere three days, as this writer tried to do. (As a result, the oft-repeated word “ethos” soon lost its meaning

for me. “Eponymous” went out the window shortly after.)

It’s a gutsy venture to try to chronicle a culture as alive and ever changing as Burning Man. However, if and when people look back on the history of this desert civilization, where money is discouraged, spectators are banned, drugs are like candy, clothing is optional, and gentle weirdness prevails, I hope they refer to this comprehensive, sharply written volume as a trusted resource. ∆

Arts Editor Anna Weltner wants you to participate in her arts editorship. Barter at [email protected].

Comments