Common Core. Common Core. Common Core. Are you sick of hearing that phrase yet? Well, you better get used to it, because many educators think it’s going to be here awhile. Whether you think it’s a scheme masterminded by the federal government to brainwash our children or not, it’s changing the way teachers teach, students learn, and how schools are testing. For New Times’ annual Education Today issue, we bring you four separate (but equal) stories about how Common Core is affecting local school districts. We talk technology (or the lack thereof), how curriculum’s being shaped without officially sanctioned course materials, what could help English learners, and what teachers think of things.

—Camillia Lanham, editor

Connecting the commons

Areas schools fine-tune their connectivity after the first year of digital assessments

BY JONO KINKADE

California survived the first year of Common Core, the Internet still works, and the sky has yet to fall.

That’s the general gist from local educational officials—at least technologically speaking—when it comes to the wires plugged into a new educational regime.

The first year of testing K through 12 students along the Common Core State Standards is complete in California. As the nationwide assessment overhaul—from pencil and paper to keyboard and screen—takes root, educators are working out the technological bugs that come with administering the Smarter Balanced Assessment.

No longer are students made to tediously and properly fill in hundreds of bubbles with special pencils. Testing has gone digital, and it can be daunting for schools to facilitate thousands of students, all using computer devices to push test results through the same mainframe during a limited time window.

Generally speaking, SLO County has done pretty well, and school districts rose to the challenge, said Phil Trott, director of information technology services for the San Luis Obispo County Office of Education.

“In our county, the transition to the test and the actual test really came off very smoothly. It was taken very seriously,” Trott said. “A lot of thought was put into it. But in the end, things went very well, and we’re thankful that they did.”

Trott oversees technology and connectivity for the county education office, which serves as the Internet service provider to districts. During the assessments, schools send everything to the office, which in turn routes it to CENIC (Corporation for Education Network Initiatives in California), a nonprofit that essentially provides high-speed, reliable Internet service in bulk to education institutions throughout the state.

For testing and the large-scale transfer of data to happen effectively, there are many dots to connect, starting with having enough devices for students, adequate wireless Internet to support those devices, and the network infrastructure to provide that wireless.

Trott says that this is one year down, and there are many, many more to go.

“Our work is not done. We’ve got to maintain that level of reliability,” Trott said.

School districts are looking to continue improving their connectivity—or the total reliability and speed of their Internet connection—and to expand the applied use of technology within classrooms. Depending on the district, that process means something a little different.

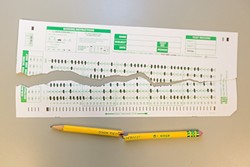

- PHOTO BY KAORI FUNAHASHI

- NO MORE SCANTRONS: The way California teaches and tests children is changing, but as the lead-filled bubbles fade into history, will some students have a harder time adjusting than others?

Lucia Mar Unified School District—the biggest district in the county, educating more than 10,600 students throughout South County—is in the midst of a $3.3-million upgrade guided by its 2014 to 2017 technology plan. With that update will come additional future costs for maintenance and upgrades. All of that will be expensive, but the district has been planning to meet its lofty goals.

“Our district saw this coming like a lot of districts did,” said Jim Empey, a director of curriculum for the district. “Our goal one day is to have Internet access in every classroom on every campus.”

In addition to anticipating the need to have adequate infrastructure in place so that a large amount of students can take the tests without any major hiccups, Lucia Mar joined the testing pilot program a year before the real assessment. That allowed the district to prepare.

“It’s not as easy as plugging a router into the wall and plugging in the Chromebooks,” said Hillery Dixon, also a Lucia Mar curriculum director.

Empey said a certain degree of computer literacy is important, so students are getting tested on what they know, not their ability to work a computer.

Because the district has a vision to be “the model district for 21st century learning in the nation,” Dixon said, they were already relatively set up for Common Core assessments.

“We would have been doing this anyway,” Dixon said. “It’s what is good for the kids.”

Out in Shandon, the rural community 17 miles east of Paso Robles, the picture is a bit different.

There, Internet access is harder to come by, and computer literacy is more spotty. The Shandon Unified School District has Internet, but it’s slow.

Superintendent Teresa Taylor told New Times that the district does have computers, and they’re expecting to get several more next year, but the issue is getting those devices online.

During the 2015 spring assessments, getting students connected to the test was a challenge, one they only pulled off using the school’s entire Internet connection for nothing but testing. And that was only possible with a temporary measure that doubled the Internet speed.

“We only have the connectivity of one class at a time to be on there,” Taylor said.

Like Lucia Mar, Shandon is looking to increase the use of technology in the district’s day-to-day educational mission for its 300 students.

“We want [the students] to have access to technology at all times,” Taylor said. “It’s part of the curriculum. It’s interwoven in the curriculum, not something that you do for 2 1/2 weeks.”

In the first round of testing, Shandon students weren’t able to practice taking the test beforehand because the district didn’t have the connectivity to allow it.

“I feel like our students were at an unfair disadvantage because they weren’t used to that kind of test,” Taylor said. “We’re desperate. It limits what we can do—curriculum-wise, fair testing of our kids—we’re very limited without it.”

But hope is within sight for the district. Actually, it’s less than a mile away.

With Trott’s help, the district wants to connect to a main communication artery that runs through the area near Highway 46. There, the county owns some dark fiber, or unused fiber optic cable, which is often installed during the construction for possible future use.

“The county has been very generous with making two of those strands available,” Trott said.

The Shandon Unified School District is waiting on funds from the state’s Broadband Infrastructure Improvement Grant, a program with $26.7 million in funding to improve network connectivity infrastructure.

That aim was to get the connection secured by spring 2015, but Taylor said it’s taken longer than expected, in part because the state program didn’t quite realize where Shandon was and what the project would require. In the meantime, that dark fiber is sitting there, un-utilized.

“It’s been a mile away from our school for 10 years, but nobody has been able to hook it up,” Taylor said.

Soon, Taylor hopes, the installation of a few switches, cables, and boxes will bring a new educational chapter online.

“I feel like it will take us from being behind to putting us ahead, because we’re so small that we can make it make a difference,” Taylor said.

Staff Writer Jono Kinkade is a proud product of Atascadero Unified School District, where he took way too many STAR tests. Contact him at [email protected].

The way to teach

California hasn’t yet fully adopted texts to go with the new state standards, but educators still need to instruct

BY CAMILLIA LANHAM

Common Core was officially adopted in 2010, but schools and students didn’t just wake up one day with a new set of standards ready to go, well understood by districts, and being taught in classrooms.

Rolling things out into an extensive education system that teaches children in the nation’s most populated state takes a little bit of time. It took a couple of years for the state’s Board of Education to fully approve standards for each subject.

And while that’s done now, not all those subjects have state approved textbooks and materials to go with them. At this point, the California Department of Education’s board has approved textbooks for math and is expected to do the same for English/language arts this November. One year after that will be history/social science, and the following year should be science. But schools are still expected to teach Common Core in classrooms, and students will be tested on the new Smarter Balance Assessments in math and language arts once again.

How?

In the San Luis Coastal Unified School District, the changes started four years ago. Once standards were adopted, the district looked at the way it was teaching—“pedagogy,” as Rick Robinett, assistant superintendent of personnel, innovation, and educational services, called it—because that’s really the key thing that changed.

“We’re actually excited because, I think, it’s a thinking curriculum,” he said. “It really gets to students applying knowledge rather than gaining knowledge.”

He uses the assessments as an example. It’s no longer A, B, C, or D that answers a question; it’s explaining your answers. The standards are still there, Robinett explained, but the way students need to get to them is different.

And that’s why they started with pedagogy, said Amy Shields, the district’s director of learning and achievement who spearheads curriculum development for elementary grades. Common Core has changed the way teachers in the district feed students knowledge.

“It’s that real shift in that it’s not all about lecture and hope that kids get it,” Shields said, it’s about giving students more than a cursory understanding of something. It’s about more than ensuring students memorize multiplication tables. It’s about them understanding why three times three equals nine. “If you adopt a new Common Core textbook, but still teach it the same way, it’s not going to be successful.”

- PHOTO BY KAORI FUNAHASHI

- BEHIND CLASSROOM DOORS: The adoption of Common Core education has made its way to California classrooms. Now it’s up to local educators to teach the new standards to their students.

That basic concept is making it hard to find textbooks for things like math, she added, because while many of the textbook creating companies quickly “changed” some of the content, the teaching materials to go with them didn’t change. With everything that’s out there, Shields said there was really only one set of math materials that were an option for San Luis Coastal.

The Bridges Math Program from the nonprofit Math Learning Center was perfect for the district because it aligned with new math standards and gives teachers the resources they need to teach the Common Core way—i.e. to stimulate discussions and talk about the different ways to arrive at correct answers.

Shields said for English/language arts, the district’s already been teaching a curriculum that aligns nicely with Common Core for the last 12 years.

The Paso Robles Joint Unified School District approached things slightly differently. Teachers and administrators took a year getting to know the new standards and then spent a year implementing them in classes. Now, the district awaits feedback from the state (assessment scores from 2014-2015) so it can see what worked well and what needs to be improved.

“That part of the feedback loop will inform our next round [of changes],” said Babette DeCou, the district’s chief academic officer.

But without a set of textbooks and materials to pull from, things have been difficult. Basically, the district looked at all the materials it was using in the classroom, threw out what didn’t work, kept what did, and sought out resources to fill the gaps—which, DeCou added, is what all the districts did.

“It’s a really hard thing,” she said.

But DeCou thinks it will make teachers stronger in the long run.

“When that happens, you better really understand the standards, because you’re pulling from materials without the way to teach them,” she said. “So, in a way, you’re a better consumer of the standards.”

Most approved curriculum materials come with a teacher’s guide; you’ve seen them if you’ve ever snuck a peek at the instructor’s version of a textbook. But without state adopted texts and resources to pull from, teachers finding these new materials have to come up with their own way of teaching them so they’re abiding by the new standards.

The district brought in new math textbooks/resources off the state-approved list—the math standards changed dramatically, as in what topics are taught in each grade—and will be field testing from the language arts materials once those are approved in November by the state Board of Education. The new math texts will be fully incorporated in kindergarten through sixth grade for this upcoming school year.

Although it may seem like a super slow rollout, DeCou said things worked out pretty similarly 15 years ago, when the last state education standards were introduced.

And before that happened, there wasn’t really a unifying standard across the state for what was taught in each grade level. So a third grade class in one district could be learning something different than one in another district.

The great thing about actual standards is “it took away the conversation of what we should be teaching at a certain grade level. … Plus, you can talk about the best way to teach. But that’s a really great conversation to have,” she said. “There’s some real power to it … and you can really leverage resources.”

She added that the way these new standards are being introduced is probably better than the last. At that time, the tests weren’t necessarily assessing what students were supposed to be learning.

“At least this time, our state assessments are aligned with where we want these kids to go,” DeCou said.

Editor Camillia Lanham can be reached at [email protected].

Mind the gap

As schools move to implement Common Core standards, some kids could be left behind—can dual immersion pick up the slack?

BY KYLIE MENDONCA

By the time kids exit sixth grade, they are experts at filling in bubbles. California kids have had four years of STAR testing by then, evaluating math, reading, writing, science, and history, and have likely taken a dozen practice tests to boot. They know strategies of elimination when the answer is unknown. They know how to make best guesses, and to re-read the question when they’re stumped. Maybe they’ve been taught calming meditation techniques, or maybe they’ve got an Adderall prescription for laser focus. But, as the 43rd president of the United States pointed out, “Rarely is the question asked: Is our children learning?”

The new education model, which has been rolled out in 44 states so far, does ask what are kids learning. Common Core is the latest public education overhaul, replacing No Child Left Behind, and whichever educational fad preceded that. Proponents say it is a not just a different way of testing, it’s a better way of learning. California began implementing Common Core standards in 2010, and last school year the transition was complete.

The idea is simple: Don’t just teach kids how to pass the grade or bubble inside the line. Teach kids to think critically and express themselves, and start young. At an age when many kids are happy to explore the subtleties of paste and finger paint, Common Core asks them to write an opinion piece and cite two sources. In all subject areas, including math and science, there is an emphasis on using complex and precise language to express concepts. Sounds great, right? Now, imagine you don’t speak English, because in California, more than a quarter of kindergarteners don’t. ¿Que?

Statewide, 23 percent of public school kids are classified as English learners (EL), according to the California Department of Education (CDE). Meaning English is not their first language, it’s not spoken at home, and they are not proficient yet. Already there is a known achievement gap between kids who enter kindergarten fluent in English and kids who are learning. In SLO County, second graders who were native English speakers performed about twice as well on English language arts and math, according to the CDE. This gap deepens by 11th grade in language arts but becomes less pronounced in math skills. With the new emphasis on complex language use, even in math, many people in education are worried the gap could widen. The Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC) said, “[Common Core] is expected to pose particular challenges for EL students, who are already struggling to learn basic English.”

The majority of kids who are learning English as a second language are in elementary school. As kids grow and become fluent, they phase out of that category, and become “fluent English proficient.” Here’s the amazing thing: kids who were English learners, who later become fluent, perform better on standardized tests in fourth grade than English learners and kids who only speak English, according to a report from the PPIC. Unfortunately, the gap appears again in seventh grade.

Of the 1.4 million public school kids who are English learners, about 5,400 live in SLO County. That number of kids has doubled since 1996, according to the CDE. During that same time, one school in SLO has found a way to address that achievement gap, and keep students performing at a high standard through high school.

Rick Mayfield, the principal at Pacheco Elementary in San Luis Obispo, said that English learners who come to Pacheco have far better outcomes than English learners across the state. English learners at Pacheco also learn to speak English fluently faster than their peers.

“English learners are not students who come to school with a deficit,” Mayfield said. “They are just as smart as native English speakers.”

Surprisingly, Pacheco kids learn English by speaking Spanish. Pacheco is a dual immersion school, in which about half the kids are native Spanish speakers, and half the kids are native English speakers. Instruction is primarily in Spanish in kindergarten and transitions to English instruction by the end of sixth grade. By graduation, Pacheco kids speak both Spanish and English with ease—and 100 percent of English learners become proficient.

Historically, Pacheco kids have done very well on standardized tests, especially when the scores are separated by native language.

“We don’t try to compare ourselves from one school to the next,” Mayfield said. “We compare native English speakers to native English speakers, and native Spanish speakers to native Spanish speakers. And we track it all the way through high school. Our native English speakers outperform other native English speakers, and our native Spanish speakers outperform other native Spanish speakers.”

Mayfield’s student body has twice the number of English learners as most California schools, but he’s not sweating the new requirements.

“For 20 years,” Mayfield said, “everything we’ve asked the kids to do, they’ve risen to the occasion.”

Pacheco began implementing Common Core standards three years ago. He said students do the same work as other kids in the district, the only difference being it’s in two languages. Mayfield said parents have been asking a lot of questions about the new curriculum, especially the math, but he’s not seen any pushback.

“This is really higher-level thinking,” Mayfield said. “I think it’s very valuable, and over time we’re going to get kids who are more capable of complex thinking.”

In 2015, kids across the country took the first standardized tests based on Common Core. The results are in but aren’t expected to be released until this fall.

Staff Writer Kylie Mendonca can be reached at [email protected].

Common Core in the classroom

Teachers work to implement new education standards

BY CHRIS MCGUINNESS

When you take a look at the information on the California Education Department’s website, the language surrounding the state’s explanation of Common Core Curriculum standards is dripping with bureaucratic technobabble.

“While the Standards delineate specific expectations in reading, writing, speaking and listening, and language, each standard need not be a separate focus for instruction and assessment,” reads the department’s explanation of the state’s Common Core aligned English and language arts curriculum.

A summary of documents on the state’s Common Core math standards is no less obtuse.

“… the CA CCSSM require not only rigorous curriculum and instruction but also conceptual understanding, procedural skill and fluency, and the ability to apply mathematics,” it reads.

But to truly understand what the language in those documents, as well as the guidelines that govern the state’s implementation of Common Core, actually mean for students, one only needs to step into an actual classroom and ask the teachers tasked with making Common Core’s educational goals a reality. A post-Common Core classroom is a much different environment than the one Anna Elliott walked into 30 years ago.

“When I first started teaching, there were really no standards at all,” said Elliott, who teaches third grade at Dorothea Lange Elementary School in Nipomo. “There was no structure or guidelines.”

- PHOTO BY KAORI FUNAHASHI

- DIFFERENT MATH: Local districts have the new sets of Common Core standards to teach, but are designing their own curriculum to get there.

Common Core State Standards was a national initiative rolled out in 2010 with the goal of standardizing curriculum across states and better preparing students for college and the workforce. The states themselves are able to customize that curriculum. Adoption of Common Core by states isn’t mandatory, and while some heavily conservative states such as Texas and Oklahoma declined to do it, California jumped at the chance to participate.

“The Common Core State Standards (CCSS) were voluntarily adopted by the California State Board of Education and local educational agencies [LEAs],” state education department spokesperson Tina Jung wrote in an email response to questions from New Times. “The CDE does not track which LEAs have adopted the CCSS, however, we have heard anecdotally that most LEAs have adopted them.”

Common Core isn’t just a change in curriculum standards but in the way those standards are taught. Common Core focuses on developing students’ critical-thinking and analytical skills, shunning wrote learning for guided problem solving.

“Rather than the teacher simply telling them what the answer is, they want the kids to figure it out with guidance from the teacher,” Elliott said.

To help the young children in her classroom understand the standards and critical thinking concepts, Elliott uses everything from hands-on manipulatives, to songs and visual aids. Using those teaching tools to help students understand what they are learning isn’t much different that what was done before the adoption of Common Core.

“They are leaning by doing, and that’s not a massive change when you talk about kindergarten through third grade,” Elliott said. “You are trying to make it real for them. You want to embed the learning in what are doing.”

The new standards not only apply to elementary school, but to secondary education as well. Nipomo High School math teacher Donna Kandel said that high school students now have to deal with Common Core’s more rigorous curriculum standards without the benefit of having learned them while they were in lower grade levels.

“Those kids came up under a different system,” Kandel, who is also the president of the Lucia Mar Unified Teacher’s Association, said. “They came up under a testing regiment that was more focused on rote answers and multiple choice questions. Teachers are going to have to make adjustments for that.”

While Kandel and Elliott work to integrate Common Core into their classrooms, both were critical of the state’s newest testing regime. Results from the first round of the state’s new assessment tests will be released this year. Kandel worried that attaching high-stakes testing to common core would result in the same problems under the state’s previous education system.

“We had so many years of teaching to the test, and I think that’s been really detrimental to education,” she said. “Some parts of Common Core are an improvement, but with the testing … we could end up in the same situation where we are teaching to the test.”

Elliott also raised concerns about testing.

“It’s just gone way to far,” she said.

When it comes to measuring student success, Elliott said she likes to see her students be able explain how they got their answers, and show they’ve internalized the concepts they are learning. That could be in writing, or even by drawing a picture.

“To me, the test is a kind of the ‘inside the box’ way of showing that they learned. … To me, the test is the opposite of what Common Core wants. It has to go beyond just a test.”

Staff Writer Chris McGuinness can be reached at [email protected], or on Twitter @CWMcGuinness.

Comments