Like so many debates these days, this one started with a social media post.

In January, as a group of San Luis Obispo residents honed plans to install a monument in Mitchell Park of former U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt—who stopped by SLO in 1903 and gave a speech along his tour of the West—SLO Mayor Heidi Harmon found herself unable to shake a total lack of enthusiasm for the idea.

- Cover Photos By Jayson Mellom; Teddy Roosevelt Photo Courtesy Of Pierre Rademaker. Cover Design By Alex Zuniga

- MONUMENT DEBATE While a group of locals raise funds to erect a Theodore Roosevelt monument in Mitchell Park, some say the former president is a poor choice for SLO's first statue of an individual.

"I just thought, 'I don't understand this at all,'" Harmon told New Times. "I don't understand the why of it, on every level. Why here, why now, why him, why not multiple other people of different groups and representations, and then why monuments at all?"

Especially in light of the recent tumult across the country about monuments depicting controversial historical figures, Harmon was uncomfortable with the idea of permanently casting the 26th president in bronze in a city park.

So the mayor went on Facebook.

"Wondering why we need more monuments of white men at this point," Harmon wrote in a Jan. 10 post that drew more than 170 comments in response.

"This is not about being against Teddy Roosevelt," she wrote, "but rather expanding the conversation to shed some light on the disparity in who gets representation in our cities."

As intended, her post sparked what became an intense community debate over the proposed monument—bringing to the fore difficult questions about our history, the enduring traumas and transgressions of the past, and the purpose of public art.

Since her post, local indigenous groups have come out against the monument, sharing painful reminders of Native American oppression during that era, as well as words that Roosevelt himself said, like in the 1880s: "I don't go so far as to think that the only good Indians are dead Indians, but I believe nine out of 10 are, and I shouldn't like to inquire too closely into the case of the 10th."

In February, the monument's sponsors—led by former SLO City Councilmember John Ashbaugh—announced that they had suspended their project application pending a City Council discussion on July 16 about monument policy. City leaders will decide then: What kinds of monuments, if any, should be accepted on city property?

As the conversation moves forward, Ashbaugh continues to vouch for the monument—and for Roosevelt as an environmental and social progressive in his time. Ashbaugh said the president's one-hour stop in SLO more than a century ago planted a seed for future conservation efforts locally.

"I think all of us deserve to be judged in the context of our times," Ashbaugh told New Times. "The way I look at it, if he had not come, if he had bypassed SLO on this trip, we would probably be a different place than we are now."

'A very important hour'

On May 9, 1903—116 years ago to this issue's publication date—President Roosevelt's train pulled into the South Pacific Railroad Station in SLO at around 5:30 p.m.

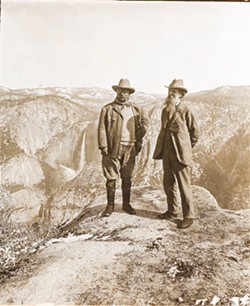

- Photo Courtesy Of The Library Of Congress

- THE GREAT LOOP TOUR A few days after former President Teddy Roosevelt gave a speech in San Luis Obispo, he and Sierra Club founder John Muir (right) met in Yosemite. Roosevelt's 14,000-mile tour through the West in 1903 influenced his later establishment of national parks and monuments.

Heading north from Santa Barbara, the stop marked roughly the halfway point in the president's 14,000-mile railroad trip across the Western U.S., which would next take him to Santa Cruz, San Francisco, and then Yosemite to meet Sierra Club founder John Muir. The Great Loop Tour, as the whole journey was called, influenced Roosevelt in later establishing dozens of national parks, monuments, forests, and wildlife preserves.

During his short visit, Roosevelt toured Mission San Luis Obispo and then went to an open lot called the Murphy block (today, Mitchell Park), where he spoke to a crowd of about 10,000 people—more than half the county's population at the time.

"He was the first real media celebrity as a president," said Ashbaugh, a history faculty member at Allan Hancock College. "He was a hero of the Spanish-American War, but that's all people really knew about him, and that he was regarded as a reformer. People needed that, just like we need it now."

In a 15-minute speech, Roosevelt gave praise to SLO's agricultural abundance and sustainable way of life.

"We have passed the stage as a nation," Roosevelt said in his address, "when we can afford to tolerate the man whose aim it is merely to skin the soil and go on; to skin the country, to take off the timber, to exhaust it, and go on. ... We wish to hand over our country to our children in better shape, not in worse shape, than we ourselves got it."

Ashbaugh detailed Roosevelt's local stop in a 2015 article in the local publication La Vista: A Journal of Central Coast History. In his account, Ashbaugh makes the argument that "in that brief hour, we can find a touchstone for the fierce spirit of environmentalism. ... Succeeding generations—including our own—would follow Teddy Roosevelt's clarion call in efforts to preserve landmarks like Morro Rock, the Nipomo Dunes, and the Carrizo Plain."

Roosevelt's visit, according to Ashbaugh, left an imprint on local leaders who were present, including future SLO Mayor Louis Sinsheimer, whose father was on Roosevelt's welcoming committee.

"He was like the original progressive in SLO, just like Roosevelt was nationally," Ashbaugh said about Sinsheimer, and added, "[Roosevelt] only spent an hour in SLO, but it was a very important hour."

In the monument mix

While SLO is a town with plenty of public art, to date there are no statues or monuments on city grounds honoring specific individuals.

- Photo By Jayson Mellom

- PUBLIC ART Paula Zima, the artist behind Mission Plaza's bear and child sculpture, is the sculptor for a proposed monument of former President Teddy Roosevelt. Objections from local indigenous groups and others have put the project on hold.

Subjects depicted in existing sculptures—like the Chinese rail worker memorial (Iron Road Pioneers) by the train station, the bear and child (Tequski wa Suwa) in Mission Plaza, and the Plains Indian (Oh Great Spirit) on Prado Road—are symbolic and nameless.

"Those are caricatures of cultures and people who were important in our history," SLO City Manager Derek Johnson explained. "This [the Roosevelt statue] is different; this is to an individual. I think it adds a totally different element."

To Ashbaugh, Roosevelt is a worthy candidate for the city's first monument in Mitchell Park.

"Just in the field of conservation, the guy deserves recognition as a great leader of our nation," Ashbaugh said.

Ashbaugh's idea for the monument drew interest from New Mexico artist Paula Zima, a former SLO County resident and the artist behind the bear and child statue in Mission Plaza as well as both of the Los Osos greeting bears, among other public artworks. She agreed to sign on to the project.

"I've been a lifelong fan of Teddy Roosevelt," Zima told New Times. "I love to sculpt. I took it on as a challenge and found I really love doing portraits."

As the ball got rolling on the concept, Ashbaugh linked up with Arts Obispo for fiscal sponsorship (to receive private donations) and formed a monument committee that began meeting regularly in 2017 about the project. The group developed a vision of a bronze Roosevelt, seated at Mitchell Park in a redwood grove and wearing the same clothes he wore with Muir in Yosemite, with scattered boulders for public seating, informational plaques, and tributes to other local conservation heroes.

- Photo Courtesy Of Pierre Rademaker

- MAQUETTES These maquettes offer the public an idea of what a proposed Teddy Roosevelt monument in Mitchell Park would look like.

"The idea is you're sitting around a campfire with Teddy Roosevelt," Zima said, adding that she envisions the casting process taking place locally in Paso Robles.

The group started raising money to hit an estimated $150,000 target, knowing the project would eventually require approval by an arts jury and city advisory bodies—standard procedure for public art in the city. The committee had raised about $50,000 and produced two maquettes of the statue, before community scrutiny befell the proposal.

"We had no negative feedback until earlier this year," Zima said.

'Continuum of harm'

Not everyone in town felt the strong, local connection to Roosevelt that Ashbaugh did.

Mayor Harmon wondered about other candidates for a statue, like women's rights activist Susan B. Anthony or Hearst Castle architect Julia Morgan, who both spent time and made an impact in SLO County. Those choices would also break the national trend of memorializing white men.

But Harmon also feels wary of monuments in general.

- Photo By Jayson Mellom

- FUTURE MONUMENT? This redwood grove in SLO's Mitchell Park is where former City Councilmember John Ashbaugh and others hope to install a monument to Teddy Roosevelt, who delivered a speech in 1903 at the then-empty lot.

"Monuments are sort of implicitly problematic," Harmon said. "When we pick off one person, especially from our past, undoubtedly these are complex humans who have done some great things and, generally speaking, some challenging things that we no longer respect."

Harmon's Jan. 10 Facebook post raising questions about the project sparked an intense response from citizens and groups agreeing—and disagreeing—with her objections.

Local indigenous leaders expressed opposition, pointing to Roosevelt's views and policies toward Native Americans. A 2016 article in Indian Country Today described Roosevelt's presidency from 1901 to 1909 as, "marked by his support of the Indian allotment system, the removal of Indians from their lands, and the destruction of their culture. Although he earned a reputation as a conservationist ... Roosevelt systematically marginalized Indians, uprooting them from their homelands to create national parks and monuments, speaking publicly about his plans to assimilate them, and using them as spectacles to build his political empire."

Similarly, some locals adopt this view of Roosevelt's legacy. In a Jan. 15 letter sent to the SLO City Council, the Northern Chumash Tribal Council (NCTC) urged the city to reject the monument "celebrating a president that by today's standards would be war criminal."

"I would like to ask the council to send a clear message that [the] city and community of SLO stand against racism and violence towards the Indigenous communities," read the letter, signed by NCTC Vice Chairwoman Violet Sage Walker.

"It just causes a continuum of harm to our people," Sage Walker told New Times. "To have to continue to defend our right to be here, and to tell the story of our community and what really happened here."

Mona Olivas Tucker, chair of the yak tityu tityu yak tihin-Northern Chumash Tribe, said her council also met and voted against supporting the project.

"We do know that Mr. Ashbaugh and his committee did work very hard on that project, but my tribal council didn't understand the connection from Teddy Roosevelt to the community of SLO," Tucker said. "We also thought maybe there should be more community input, because it's not public art, it's a monument. It's a testament to President Roosevelt. ... There was some disregard—and that's a mild word—in Mr. Roosevelt's opinion of indigenous people.

"But aside from that," Tucker continued, "President Roosevelt has been well [recognized] throughout the United States. ... How many people do you know have a 60-foot carving of their face on the side of a mountain?"

In response to the budding opposition, the Roosevelt monument committee proposed the addition of an "interpretative sign" at the site that would include "a frank description of Roosevelt's overall record on racial matters."

"We invite our Native American neighbors to help us write this narrative," the monument committee wrote in a Feb. 12 piece published in the Tribune. "One of the objectives of public art is to foster communication and debate among those whom it serves."

NCTC Chair Fred Collins penned a response with a simple message: "Stop this cultural genocide project."

"To honor this man ... in our Northern Chumash Lands is one of the lowest ideas we have ever heard, a man of genocide, people should be ashamed," Collins wrote in the Feb. 16 letter. "We want to forget this monster."

The swift and sudden backlash put Ashbaugh and the committee on its heels. The City Council voted to agendize a discussion about city monument policies, which will take place at a July 16 meeting.

In the interim, Ashbaugh has reached out to individual City Council members to request meetings about the project. Those meetings happened in some cases. In others, like with Harmon, they were rebuffed.

"I cannot in good conscience abide your request," Harmon wrote to Ashbaugh on Feb. 21. "There is no configuration of your proposed idea that is worthy of my evaluation. It is wrong on its face and for me to pretend otherwise would be false and a waste of both our time. ... I would invite you to truly hear the very legitimate concerns of many regarding the deep and continuing pain that President Roosevelt and many others have caused."

Conflicting perspectives

Ashbaugh said he doesn't dispute most of the critical statements made about Roosevelt, and about the widespread oppression and violence against minority groups in the late 1800s, early 1900s.

"The Indians were, for the most part, treated very, very poorly throughout this period," Ashbaugh said. "A lot of [Roosevelt's] writings and early speeches reflect the sort of colonialist, white supremacist outlook. That was the way he was trained. But you have to look at the whole arc of the man's life."

By Roosevelt's death in 1919, Ashbaugh argues that the 26th president had "transformed into what most people could look at as the first white civil rights leader of the 20th century."

- Photo By Jayson Mellom

- STATUE DEBATE All of SLO's existing public statues depict symbolic subjects, like this Chinese rail worker, as opposed to specific historic individuals. In July, the City Council will discuss its monument policy.

"He's entertaining Booker T. Washington in the White House in 1901. He advocates against the most evil, abhorrent aspect of the Jim Crow era, lynching. ... By the time he's elected president in 1904, he has six Native American tribal [chiefs] marching in his [inaugural] parade," Ashbaugh said. "So you can cherry-pick things he says here and there that make it look like he's fundamentally racist, but he's not. He was very much dedicated to the civil liberties of all Americans and of immigrants."

That perspective is challenged by community members with a different perspective and a different heritage. While Ashbaugh said, "We have to accept the fact that the hand of history writes and having written, moves on," for many, the traumas inflicted by America's history of colonialism and racism remain ever-present.

"It's a scar," Sage Walker said. "The reaction from the monument people was that they could change our minds. Those kinds of assumptions are insulting on face value.

"People love national parks," she continued. "We love them too because that's where we used to live."

The debate over statues and monuments—what they signify, what history they promote, and whether some are best removed or omitted—isn't unique to SLO, nor is it always confined to cyberspace. Two years ago, one of the largest white supremacist rallies in recent history took place in Charlottesville, Virginia, in protest of a city decision to remove a Confederate monument to Gen. Robert E. Lee. It ended in bloodshed—the murder of counterprotester Heather Heyer.

That broader context is inescapable for this new monument proposal, members of both camps admitted.

"Times are different," Zima, the sculptor, said. "There's been all this awful stuff in Charlottesville. The nation has this contentiousness that is more dominant. ... I guess we could just not have any sculptures of any human being and keep everything abstract. I don't even totally agree with taking down the sculptures of the Civil War. Rather than tearing down old sculptures, new information should be brought to light."

SLO city leaders and community members will ultimately decide this summer how to best approach a difficult public art dilemma.

"This is about trying to do the right thing," said Mayor Harmon, who led the effort to agendize the city monument discussion. "In this particular case, we need to be really mindful about the fact that we are lacking diversity and that people of different backgrounds are not feeling generally welcomed and supported here. That's something we're really trying to work on as a city. This would be a step in the wrong direction." Δ

Assistant Editor Peter Johnson can be reached at [email protected].

Comments (3)

Showing 1-3 of 3